Size doesn’t matter for mammals with more complex brains, according to new research led by the University of Bath. Mammals that have developed more sophisticated brains tend to have a smaller size difference between males and females of that species. The research paper has been published in the academic journal “Nature Communications”. The study can provide new insights into mammal evolution and the role of sexual selection.

In many mammal species, the males can be bigger than the females. In some species, the females can be bigger on average than the males. This is a trait called sexual size dimorphism (SSD). For instance, male southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina), are around three times larger than females. African elephants (Loxodonta) show SSD. Males can weigh several thousand kilograms more than mature females.

In contrast, dolphins have no difference in sizes between the sexes. Humans are somewhere in between, with the average male being larger than the average female, but across the population there is an overlap.

Analysing the Genomes of 124 Species of Extant Mammal

The study involved researchers from the Universities of Bath and Sheffield, along with Cardiff University and UNAM (Mexico). The team examined the genomes of 124 extant species of mammals. The genes were grouped into families of similar attributes and functions. The size of these gene families was then calculated. The researchers discovered that those species with a big difference in size between the sexes had bigger gene families linked to olfactory functions (sense of smell) and smaller gene families associated with brain development.

Therefore, this could also mean that those species with very little difference in sizes between males and females (termed monomorphic) had larger gene families associated with brain development. The authors suggest that in species with a large SSD, traits such as the sense of smell could be important for identifying mates and territories. In contrast, mammals with a smaller SSD are potentially investing in their brain development and tend to have more complex social structures. This means they compete for mates using other means than simply using size to select who to mate with.

Corresponding author for the research, Dr Benjamin Padilla-Morales (University of Bath), commented:

We were surprised to see such a strong statistical link between a large SSD and expanded gene families for olfactory function. Even more interestingly, the gene families under contraction were linked with brain development. This could mean that those species with a small SSD have bigger gene families associated with brain function and tend to show more complex behaviours such as biparental care and monogamous breeding systems.”

Size is Important in Some Mammal Species

The research team concluded that whilst body size in some mammal species is significant, for others it does not matter so much. If size plays a role in sexual selection, then it leads on to considering how traits like SSD are shaping mammalian evolution. Is SSD in some species influencing brain and genome development?

This new research helps to illustrate the complex interplay between sexual dimorphism, gene family size evolution, and their roles in mammalian brain development and function. It provides a valuable perspective in understanding mammalian genome evolution.

The research team hope to develop this line of enquiry further. They want to investigate how testes size impacts the evolution of the mammalian genome.

Being small insectivores with fewer skull bones led to mammalian evolutionary success: Reduction in Skull Bones Led to Success for the Mammals.

The Implications for Mammalian Evolution

This research highlights the importance of considering the multifaceted nature of sexual selection and its diverse effects on different aspects of mammalian evolution and biology. The finding that body size plays a role in sexual selection for some species but not others suggests that the evolutionary pressures shaping sexual dimorphism can vary considerably across the mammalian lineage.

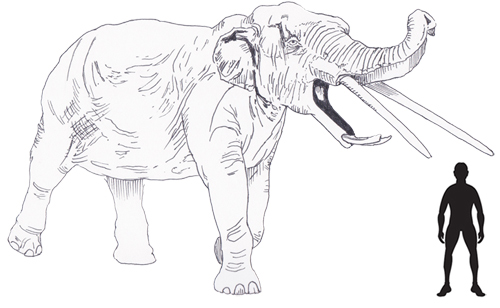

Understanding these nuanced relationships is crucial for piecing together the complex tapestry of mammalian evolution. Perhaps, a study of the fossilised remains of a particular group of mammals with descendants still living today could shed new light on when these relationships established. Could the Proboscidea Order (elephants and their relatives) provide a starting for this research? By examining the fossil records of such groups, scientists could gain a better understanding into the evolutionary processes that have given rise to the incredible adaptations found in the Mammalia.

A scale drawing of the Late Miocene prehistoric elephant Konobelodon atticus. Could a study of ancient elephants provide a fresh perspective on the evolution of sexual size dimorphism (SSD). Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Bath in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Sexual size dimorphism in mammals is associated with changes in the size of gene families related to brain development” by Benjamin Padilla-Morales, Alin P. Acuña-Alonzo, Huseyin Kilili, Atahualpa Castillo-Morales, Karina Díaz-Barba, Kathryn H. Maher, Laurie Fabian, Evangelos Mourkas, Tamás Székely, Martin-Alejandro Serrano-Meneses, Diego Cortez, Sergio Ancona and Araxi O. Urrutia published in the journal Nature Communications.

The award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Prehistoric Animal Models and Toys.

Leave A Comment