Ammonites Still a Success at the End of the Cretaceous

Ammonites were not in decline immediately before the End-Cretaceous extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs. Newly published research led by the University of Bristol has found that there is evidence to indicate that these cephalopods were still relatively successful at the end of the Age of Dinosaurs. The study suggests the fate of ammonites was not set in stone. Instead, the final few million years of their evolutionary history is more complex than previously thought. Ammonite fossils might be very familiar, but we still have a lot to learn about the ammonoids.

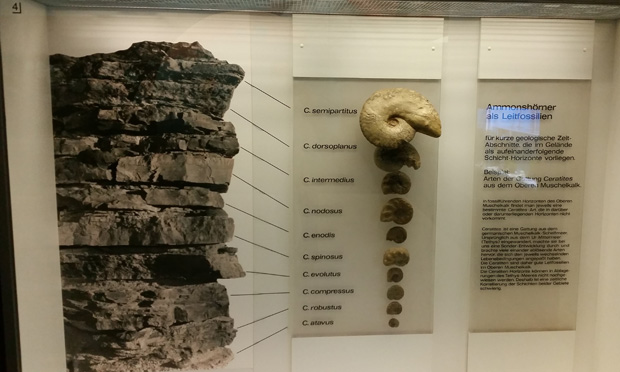

Demonstrating a sequence of ammonite fossils identified from specific strata that helps to form a biostratigraphic column. Ammonites provide an important resource to help with the relative dating of strata. It was thought these marine molluscs were in decline in the Late Cretaceous, but new research challenges this theory. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Ammonite Fossils

Ammonites were marine molluscs that flourished in the Earth’s seas and oceans for more than 350 million years before they became extinct. They died out during the same chance event that wiped out the dinosaurs, pterosaurs and most of the marine reptiles sixty-six million years ago.

It had been suggested that the extinction of the ammonites was inevitable as changes in climate and marine biota took hold. It had been thought that the number of species was in decline at the end of the Cretaceous.

Newly published research challenges this assertion. Writing in the journal “Nature Communications”, the scientists demonstrate that a detailed study of the ammonite fossil record reveals a more nuanced and complex picture.

Lead author of the study Dr Joseph Flannery-Sutherland (University of Bristol), stated:

“The fossil record tells us some of the story, but it is often an unreliable narrator. Patterns of diversity can just reflect patterns of sampling, essentially where and when we have found new fossil species, rather than actual biological history. Analysing the existing Late Cretaceous ammonite fossil record as though it were the complete, global story is probably why previous researchers have thought they were in long-term ecological decline.”

The colourful heteromorphic ammonoid model – CollectA Pravitoceras. An ammonite of the Late Cretaceous.

The picture (above) shows a model of an ammonite with an irregularly coiled shell (heteromorphic ammonite). This is the CollectA Pravitoceras ammonite figure from the “CollectA Prehistoric Life” range.

To view the range of CollectA prehistoric animal models and figures in stock at Everything Dinosaur: CollectA Prehistoric Life Models and Figures.

A Database of Late Cretaceous Ammonite Fossils

In a bid to better understand Late Cretaceous ammonite speciation the researchers constructed a new database of Late Cretaceous ammonite fossils to help fill in the sampling gaps in their record.

Co-author of the study, Cameron Crossan, a 2023 graduate of the University of Bristol’s Palaeobiology MSc programme, explained:

“We drew on museum collections to provide new sources of specimens rather than just relying on what had already been published. This way we could be sure that we were getting a more accurate picture of their biodiversity prior to their total extinction.”

Using this database, the researchers then analysed how ammonite speciation and extinction rates varied in different parts of the world. If ammonites were in decline through the Late Cretaceous, then their extinction rates would have been generally higher than their speciation rates wherever the team looked. However, the team found that the balance of speciation and extinction changed both through geological time and between different geographic regions.

Two different types of ammonite (a regularly coiled homomorphic ammonite and an irregularly coiled heteromorphic ammonite) in a Late Cretaceous marine environment. Picture credit: Callum Pursall.

The differences in ammonoid diversification in different parts of the world has not been fully explored. However, it is crucial to understanding their state prior to the mass extinction event.

Co-author Dr James Witts (London Natural History Museum), explained:

“These differences in ammonoid diversification around the world is a crucial part of why their Late Cretaceous story has been misunderstood. Their fossil record in parts of North America is very well sampled, but if you looked at this alone then you might think that they were struggling, while they were actually flourishing in other regions. Their extinction really was a chance event and not an inevitable outcome.”

Why Did Ammonoids Continue to be Successful?

To discover more about the factors responsible for the continued success of ammonoids, the team looked for possible influencing criteria that might have caused their diversity to change. There are two contrasting theories. Were speciation and extinction rates driven mainly by environmental conditions like sea temperatures and sea levels (the Court Jester Hypothesis), or by biological processes like pressure from predators and intraspecific competition (the Red Queen Hypothesis).

Co- author Dr Corinne Myers (University of New Mexico) commented:

“What we found was that the causes of ammonite speciation and extinction were as geographically varied as the rates themselves. You couldn’t just look at their total fossil record and say that their diversity was driven entirely by changing temperature, for example. It was more complex than that and depended on where in the world they were living.”

Dr Flannery-Sutherland added:

“Palaeontologists are frequently fans of silver bullet narratives for what drove changes in a group’s fossil diversity, but our work shows that things are not always so straightforward. We can’t necessarily trust global fossil datasets and need to analyse them at regional scales. This way we can capture a much more nuanced picture of how diversity changed across space and through time, which also shows how variation in the balance of Red Queen versus Court Jester effects shaped these changes.”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Bristol in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Late Cretaceous ammonoids show that drivers of diversification are regionally heterogeneous” by Joseph Flannery-Sutherland, Cameron Crossan, Corinne Myers, Austin Hendy, Neil Landman and James Witts published in Nature Communications.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Prehistoric Animal Models and Toys.