Researchers from the University of Southampton and Ohio University have recreated the brains and the inner ears of two early members of the Spinosauridae in a bid to better understand how these unusual theropods evolved as piscivores.

The spinosaurs Baryonyx walkeri and Ceratosuchops inferodios are the oldest members of the Spinosauridae family for which braincase material is known. When Baryonyx was formally named and described in 1986 (Charig and Milner), it helped revolutionise our understanding of these bizarre and enigmatic carnivorous dinosaurs. Ceratosuchops was scientifically described much more recently (2021). Several of the authors of the paper on Ceratosuchops participated in this study.

To read an article about the discovery of C. inferodios: Two New Spinosaurids from the Isle of Wight.

Having reconstructed the brains of these early spinosaurs, the researchers concluded that Baryonyx and Ceratosuchops brains were reminiscent of the brains of other theropods and lacked the specific adaptations and characteristics of later spinosaurs.

Spinosaurids – Not Your Usual Theropods

The Spinosauridae are considered unusual members of the theropod clade. Their evolutionary origins and their exact placement within the Theropoda remain uncertain. These dinosaurs are united by having a series of adaptations that indicate a more specialised predatory role within the ecosystem. They seem to have specialised in catching fish, evolving long snouts, nostrils placed further up the skull and crocodile-like jaws that were lined with large numbers of conical teeth. Adaptations that distinguish the Spinosauridae from other theropod dinosaurs such as the allosaurs, abelisaurids and tyrannosaurs, which seem to have been more generalist hypercarnivores.

Scanning the Braincase and Digitally Reconstructing the Brain

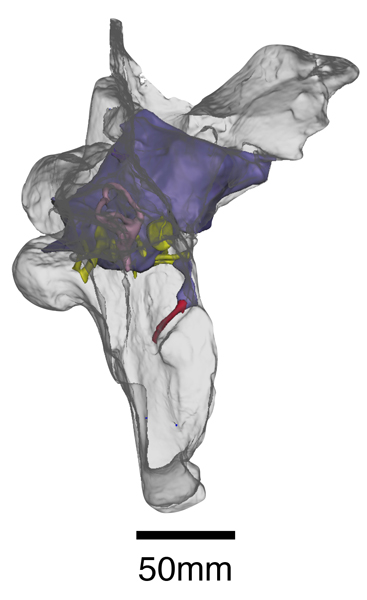

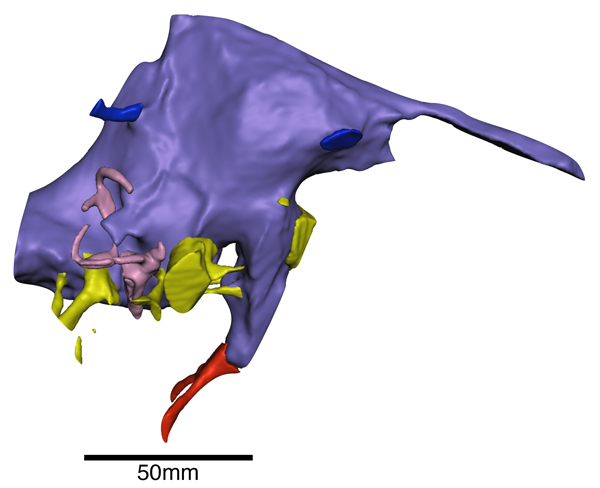

To help the researchers better understand the evolution of the spinosaur brain. The braincase fossils of Baryonyx and Ceratosuchops were scanned in high resolution. Sophisticated computer models of the brains, inner ears and related soft tissues of these two dinosaurs were created from these scans.

The digital reconstruction of spinosaur “grey matter” revealed that the olfactory bulbs, which process smells, weren’t particularly developed, and the ear was probably attuned to low frequency sounds. Those parts of the brain involved in keeping the head stable and the gaze fixed on prey were possibly less developed than they were in later, more specialised spinosaurs.

Commenting on the results, lead-author of the study, PhD student Chris Barker (University of Southampton), stated:

“Despite their unusual ecology, it seems the brains and senses of these early spinosaurs retained many aspects in common with other large-bodied theropods – there is no evidence that their semi-aquatic lifestyles are reflected in the way their brains are organised.”

Interpreting the Data

Although the fossil record of early spinosaurids is particularly poor, the researchers suggest that one interpretation of this brain study is that the theropod ancestors of spinosaurs already possessed brains and sensory adaptations that were suited to catching fish. Perhaps, as a way of avoiding direct competition with other large carnivores, the ancestral spinosaurids gradually spent more and more time hunting fish. Fish became an increasingly important part of the diet, a food resource not exploited to the same extent by other theropods. This led to the evolution of piscivorous adaptations such as longer jaws and conical teeth.

British Spinosaurs Contributing to Palaeontology

Co-author of the study, published in the Journal of Anatomy, Dr Darren Naish (University of Southampton) stated:

“Because the skulls of all spinosaurs are so specialised for fish-catching, it’s surprising to see such ‘non-specialised’ brains. But the results are still significant. It’s exciting to get so much information on sensory abilities – on hearing, sense of smell, balance and so on – from British dinosaurs. Using cutting-edged technology, we basically obtained all the brain-related information we possibly could from these fossils.”

Learning More About the Spinosauridae

The non-destructive technique of using sophisticated computerised tomography (CT scans) in palaeontology is helping to change views and perceptions about the Dinosauria. Spinosaurs remain one of the most enigmatic and controversial families within the Theropoda. This new research mapping the brains and inner ears of early members of the Spinosauridae provides a valuable contribution to the on-going discussions about the evolutionary development of spinosaurids and their role as specialist piscivores in Early Cretaceous dinosaur dominated terrestrial communities.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the contribution of a press release from the University of Southampton in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Modified skulls but conservative brains? The palaeoneurology and endocranial anatomy of baryonychine dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae)” by Chris Tijani Barker, Darren Naish, Jacob Trend, Lysanne Veerle Michels, Lawrence Witmer, Ryan Ridgley, Katy Rankin, Claire E. Clarkin, Philipp Schneider and Neil J. Gostling published in the Journal of Anatomy.

Leave A Comment