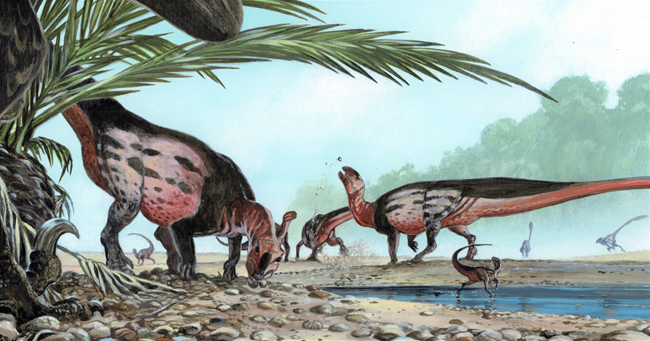

Researchers from the University of Manchester examining the fossilised remains of a Tenontosaurus have revealed new information about this ornithopod as well as evidence to support a trophic relationship (predator/prey or scavenging) with Deinonychus (D. antirrhopus).

Found in an “Ash Layer” – Cloverly Formation

The fossils of a Tenontosaurus tilletti were discovered on private land in Wheatland County (Montana) in 1994 and acquired by the University of Manchester five years later. The fossils (specimen number MANCH LL.12275) represent one of the most complete and best-preserved T. tilletti known from the fossil record. It was originally described as a mounted, articulated skeleton found with gastroliths and cycad seeds in the stomach region that had been excavated from an ash layer (Cloverly Formation, upper Aptian-lower Albian, upper Lower Cretaceous). In addition, it was stated that two broken Deinonychus teeth had been discovered in association with the cervical vertebrae (neck bones).

The original description of the dinosaur nicknamed “April” was not challenged and the specimen was displayed in the Fossil Gallery of the Manchester Museum, until 2004, when it was replaced with a replica of a Tyrannosaurus rex (“Stan” – BHI 3033).

Not an Ash Layer and No Cycad Seeds

The research team used X-ray CT scanning and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to assess so-called “seeds” and “ash” found with the specimen and revealed that they were not seeds after all and that the dinosaur did not die in a layer of ash, as had previously been suggested when it was found. The sediment, originally described when the specimen was collected as volcanic ash is actually lime mud. The team concluded that whilst the deposit might consist of a small proportion of volcanic ash, this dinosaur was not buried in a layer of ash as a consequence of a volcanic eruption.

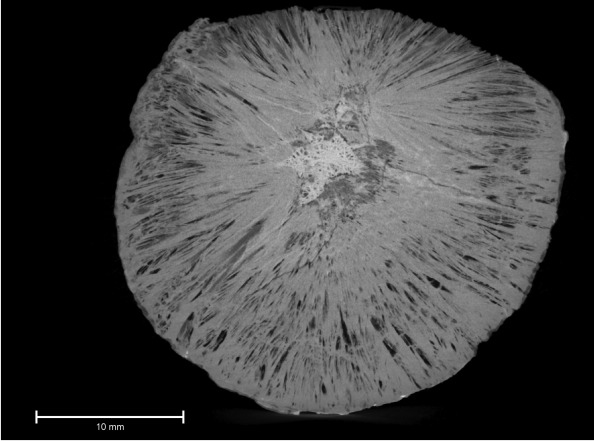

The cycad “seeds” found with the fossilised bones, measure 25 mm and 35 mm in diameter. When analysed, these spherical structures were identified as inorganic mineral concretions and not evidence of the last meal of this plant-eating dinosaur.

Evidence of Gastroliths

When first described for sale, it was stated that twelve gastroliths had been found in the body cavity. Gastroliths are stones found in the digestive tract, they help to grind up plant-material, providing mechanical assistance and aiding the extraction of nutrients from the vegetation consumed. Only a handful of examples of gastroliths being associated with ornithopods have been reported. The research team were able to confirm that the small, smooth pebbles found were most probably gastroliths. These small stones could have been washed into the body cavity of the dead dinosaur, but this idea is not compatible with the muddy sediment (representing a low energy depositional environment), in which the skeleton was entombed.

“April’s” stomach stones are the second oldest occurrence of gastroliths in an ornithopod known to science and the first gastroliths to be identified in a more derived member of the Ornithopoda.

The Diet of Tenontosaurus

Whilst gastroliths have been recorded in a wide variety of extinct vertebrates, only three unambiguous records of gastroliths in ornithopods had been reported previously. The earliest known evidence of stomach stones in a member of the Ornithopoda comes from Changmiania (C. liaoningensis) from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Liaoning Province (China), that was formally named and described in 2020 (Yang et al).

To view Everything Dinosaur’s blog post from 2020 about the discovery of Changmiania: The Eternal Sleeping Dinosaur.

The Manchester Tenontosaurus is the largest ornithopod dinosaur known with gastroliths. The confirmation of stomach stones lends weight to the assertion that the teeth and jaws of Tenontosaurus were not as effective at processing vegetation as later, more derived ornithopods such as the Hadrosauroidea. However, the flora and therefore the diet of these herbivores changed dramatically during the Cretaceous as gymnosperms (conifers, cycads and such like) were gradually replaced by angiosperms (flowering plants).

The Deinonychus Teeth

Writing in the academic journal “Cretaceous Research”, the researchers report that one of the broken teeth was now missing but the other tooth most probably comes from a Deinonychus, providing further evidence to support the long-standing assertion, originally made by John Ostrom in 1970, that Tenontosaurus was a common food item for Deinonychus.

Dedicated to Dr Jon Tennant

Doctors Dean Lomax and John Nudds from The University of Manchester dedicated this study to their friend, colleague and co-author, Dr Jon Tennant, who sadly died on 9 April 2020, before this study could be published.

Dr Dean Lomax commented:

“Jon completed his Masters at Manchester on this very specimen, in 2010. It was his idea for the three of us to come together and write this paper, which we officially began in 2018. Jon contributed significantly to palaeontology and was a massive advocate for open access. At every opportunity Jon encouraged others and was immensely passionate about palaeontology. This project would not have been possible if it was not for his research on the specimen described herein. Jon leaves a remarkable legacy behind.”

Whilst predator/prey relationships are often inferred, this specimen provides further evidence to support the hypothesis that Deinonychus fed on Tenontosaurus. The completeness and exceptional state of preservation suggests that further study of “April” may yield yet more information about the life and behaviour of this Early Cretaceous dinosaur.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from the University of Manchester in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Gastroliths and Deinonychus teeth associated with a skeleton of Tenontosaurus from the Cloverly Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Montana, USA” by John R. Nudds, Dean R. Lomax and Jonathan P. Tennant published in Cretaceous Research.

Leave A Comment