Scientists have proposed that the bizarre, chicken-sized alvarezsaurid Shuvuuia (S. deserti) had amazing eyesight and owl-like hearing, adaptations for a nocturnal hunter in its Late Cretaceous desert environment.

A Very Bizarre, Tiny Theropod

Named and described in 1998 from fossil material associated with the famous Djadochta Formation (Campanian faunal stage), Shuvuuia has been assigned to the Alvarezsauridae family of theropods. It may have been small (around 60 cm in length), but its skeleton shows a range of bizarre anatomical adaptations. It had long legs, a long tail, short but powerful forelimbs that ended in hands with greatly reduced, vestigial digits except for the thumb which was massive and had a large claw. The skull was very bird-like with disproportionately large orbits.

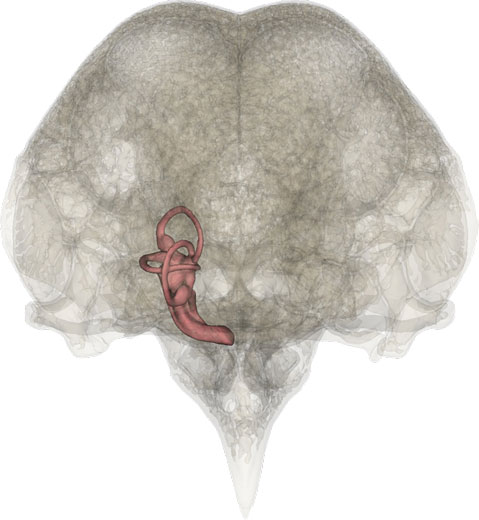

Writing in the academic journal “Science” a team of scientists led by Professor Jonah Choiniere (University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa), used sophisticated computerised tomography to examine the skull of Shuvuuia and to map this dinosaur’s sensory abilities, as part of a wider study into non-avian dinosaur sensory abilities.

Nocturnal Dinosaurs

The international team of researchers used CT scanning and detailed measurements to collect data on the relative size of the eyes and inner ears of nearly 100 living bird and extinct dinosaur species. There are more than 10,000 species of bird (avian dinosaurs) alive today, but only a few have evolved sensory abilities that enable them to track and hunt prey at night. Owls are probably the best known, but not all owls are nocturnal.

Kiwis hunt at night using their long, sensitive beaks to probe in the leaf litter for worms, whilst another bird endemic to New Zealand, the large, flightless Kakapo (a member of the parrots – Order Psittaciformes), is also nocturnal. Other birds active at night include the globally widespread black-capped night heron and the Stone-curlew (Burhinus oedicnemus) which is an occasional visitor to East Anglia in the UK.

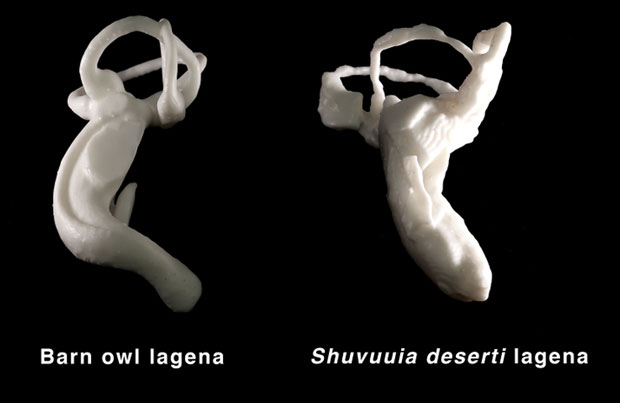

To measure hearing ability, the team measured the length of the lagena, the organ that processes incoming sound information (known as the cochlea in mammals). The barn owl, which can hunt in complete darkness using hearing alone, has the proportionally longest lagena of any bird.

Assessing Vision

To examine vision, the team looked at the scleral ring, a series of bones surrounding the pupil, of each species. Like a camera lens, the larger the pupil can open, the more light can get in, enabling better vision at night. By measuring the diameter of the ring, the scientists could estimate how much light the eye can gather.

The researchers found that many carnivorous theropods such as large tyrannosaurs and the much smaller Dromaeosaurus had vision optimised for the daytime, and better-than-average hearing presumably to help them hunt.

However, Shuvuuia, had both extraordinary hearing and night vision. The extremely large lagena of this species is almost identical in relative size to today’s barn owl, suggesting that Shuvuuia could have been a nocturnal hunter. With many predators sharing its Late Cretaceous desert environment, a night-time existence may have proved to be an effective strategy to avoid the attentions of much larger theropods.

Commenting on the significance of this discovery, joint first author of the scientific paper, Dr James Neenan exclaimed:

“As I was digitally reconstructing the Shuvuuia skull, I couldn’t believe the lagena size. I called Professor Choiniere to have a look. We both thought it might be a mistake, so I processed the other ear – only then did we realise what a cool discovery we had on our hands!”

Extremely Large Eyes

The eyes of Shuvuuia were also remarkable. Skull measurements suggest that this little dinosaur had some of the proportionally largest pupils yet measured in birds or dinosaurs, This suggests that they could likely see very well at night.

The Alvarezsauridae remain one of the most unusual of all the types of non-avian dinosaur known to science. Their place within the ecosystems of the Late Cretaceous remains controversial. Geographically widespread, a recently described alvarezsaurid from China Qiupanykus zhangi may have been a specialised ovivore (egg-eater), whilst other palaeontologists have postulated that these theropods used their strong forelimbs and large thumb claws to break into termite mounds. Perhaps, these small (most probably feathered), dinosaurs occupied a number of niches within Late Cretaceous ecosystems – including that of a nocturnal hunter of small vertebrates and insects.

To read Everything Dinosaur’s blog article about Qiupanykus zhangi and the evidence behind the egg-eating theory: Did Alvarezsaurids Eat Eggs?

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Witwatersrand in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Evolution of vision and hearing modalities in theropod dinosaurs” by Jonah N. Choiniere, James M. Neenan, Lars Schmitz, David P. Ford, Kimberley E. J. Chapelle, Amy M. Balanoff, Justin S. Sipla, Justin A. Georgi, Stig A. Walsh, Mark A. Norell, Xing Xu, James M. Clark and Roger B. J. Benson published in the journal Science.

For dinosaur models and prehistoric animal figures: Dinosaur and Prehistoric Animal Figures.

Leave A Comment