A Predator Becomes Prey as Remarkable Fossil is Investigated

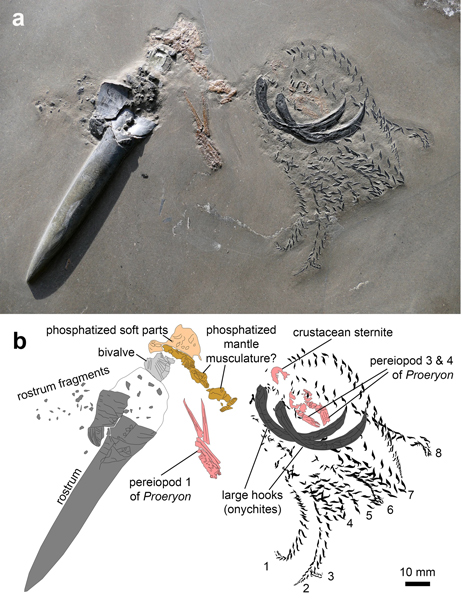

A team of scientists have interpreted a remarkable fossil from southern Germany as a rare example of predation in the fossil record. A belemnite (a squid-like animal), has been preserved with the remains of a crustacean still held in its arms. However, the belemnite (a cephalopod), never had a chance to finish its meal, its fossilised remains display damage that indicate that it too was predated upon.

The belemnite was attacking the crustacean, when it too was attacked, presumably by a vertebrate predator which the researchers postulate was a type of prehistoric shark.

Discovered in 1970

The specimen was discovered in 1970 by amateur fossil collector Dieter Weber. The fossils come from the famous Lower Jurassic, Posidonia Shale from near Holzmaden (Germany). These marine shales which are exposed in Switzerland, Luxembourg, Austria and Holland as well as Germany, are famous for their beautifully preserved but crushed fossil specimens including many types of Early Jurassic marine reptile and fish.

In Germany, these shales are known as the Posidonienschiefer Formation. The name of the formation is derived from the extensive and abundant fossils of the bivalve Posidonia bronni. Günter Schweigert (Natural History Museum Stuttgart), had been invited to view Herr Weber’s extensive private collection when he noted the fossilised remains of a belemnite (Passaloteuthis bisulcata) in close proximity to a crustacean. The remains of the crustacean, identified as an example of the decapod Proeryon, were still held in the arms of the belemnite and some soft tissue of the cephalopod had been preserved.

Damage to the Belemnite

When examined closely, the soft parts of the belemnite were far from complete and the scientists, which included researchers from the University of Zurich (Switzerland), Friedrich-Alexander-University (Erlangen, Germany), the Luxembourg National Museum of Natural History and the Ruhr-University Bochum (Germany), proposed that this was possible evidence of the belemnite having been attacked whilst in the process of subduing its prey.

Fossilised “Leftovers” – Pabulite

The specimen is interpreted as evidence of incomplete predation. The belemnite was attacked but not all of it was eaten. The assailant dropped the belemnite, which was still clutching the decapod, the remains settled on the seabed to be covered over in sediment and eventually turned to stone.

For this kind of fossil, one that provides circumstantial evidence to indicate these are the preserved remains of a dropped meal, the researchers coined the term “pabulite”. This word is derived from the Latin word “pabulum” for food and the Greek word “lithos” for stone.

What Sort of Animal Attacked the Belemnite?

As most of the belemnite soft parts between the arm crown and the calcitic rostrum are missing, the scientists postulate that this represents remains of a meal of a vertebrate predator, possibly of the Early Jurassic shark Hybodus hauffianus which is known to have eaten belemnites.

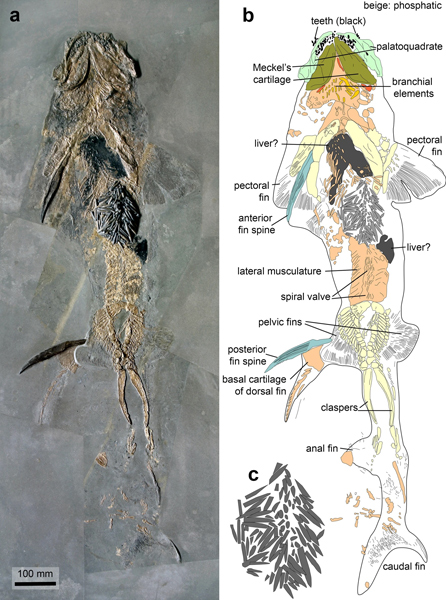

One remarkable fossil (SMNS 10062), in the collection of the Natural History Museum Stuttgart, depicts one of these small sharks which had at least 93 part or complete belemnite rostra wedged in its stomach. It has been suggested that this indigestible material probably killed the shark.

Evidence of Behaviour Preserved in the Fossil Record

These fossilised leftovers provide a glimpse into a marine food web that existed 180 million years ago. In the recently published scientific paper, the researchers speculate that vertebrate predators of belemnites, animals such as ichthyosaurs, sharks and metriorhynchid crocodiles learned to avoid the hard, indigestible rostra of these cephalopods. Instead, they bit off the soft parts and consumed them leaving the rostrum of their victim to descend to the seafloor.

The researchers suggest that the association of the complete belemnite arm crown with a complete rostrum and some soft parts represent the remains of the meal of a vertebrate predator, which had learned enough about belemnite anatomy to avoid the rostrum. This idea lends further credibility to the hypothesis that belemnite predation might contribute to belemnite accumulations (so-called battlefields, where huge numbers of fossilised belemnite guards are found together) under certain circumstances.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The scientific paper: “Fossilized leftover falls as sources of palaeoecological data: a ‘pabulite’ comprising a crustacean, a belemnite and a vertebrate from the Early Jurassic Posidonia Shale” by Christian Klug, Günter Schweigert, René Hoffmann, Robert Weis and Kenneth De Baets published in the Swiss Journal of Palaeontology.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.