It was Other Mammals not Dinosaurs that Held the Mammals Back

A team of scientists writing in the journal Current Biology have applied new statistical methods to assess how constrained different types of mammals were before and after the K-Pg extinction event that saw the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs. The researchers conclude that dinosaurs were probably not the main competitors of mammals during the Mesozoic. In addition, this study indicates that the ancestors of modern mammals during the age of the dinosaurs remained less diverse because of competition from other mammal groups.

Analysing the Variability of Mammal Fossils from the Mesozoic

The research involved scientists from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, the University of Birmingham and Oxford University and its aim was to challenge the long held belief that it was the non-avian dinosaurs dominating terrestrial environments that in effect, held back and stunted the evolution of mammals. Their conclusions such as the extinction of other mammal groups was more beneficial to modern mammals than the extinction of non-bird dinosaurs, highlights the importance of testing established ideas about evolution with new, modern methods.

Earlier Branches of the Mammal Evolutionary Tree Dominated

Co-author of the study Dr Elsa Panciroli (Oxford University Museum of Natural History), commented:

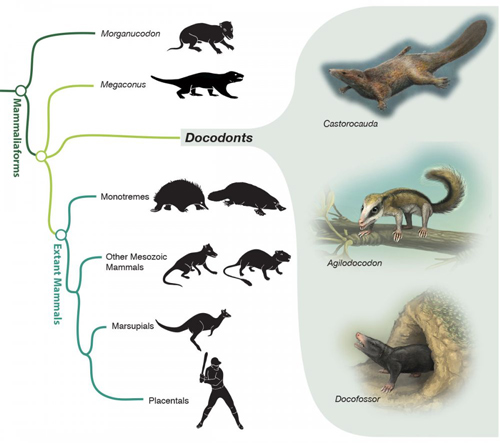

“There were lots of exciting types of mammals in the time of dinosaurs that included gliding, swimming and burrowing species, but none of these mammals belonged to modern groups, they all come from earlier branches in the mammal tree. These other kinds of mammals mostly became extinct at the same time as the non-avian dinosaurs, at which point modern mammals start to become larger, explore new diets and ways of life. From our research it looks like before the extinction it was the earlier radiations of mammals that kept the modern mammals out of these exciting ecological roles by outcompeting them”.

The Therians Kept in Check by Other Types of Mammaliaforms

Most of the mammal species alive today trace their origins to groups that expanded explosively 66 million years ago, when a mass extinction killed all non-avian dinosaurs. It was traditionally thought that, before the extinction, mammals lived in the shadow of the dinosaurs. They were supposedly prevented from occupying the niches that were already occupied by the giant reptiles, keeping the mammals relatively small and unspecialised in terms of diet and lifestyle. It appeared that they were only able to flourish after the dinosaurs’ disappearance left these niches vacant.

However, new statistical methods were used to analyse how constrained different groups of mammals were in their evolution before and after the mass extinction. These methods identified the point where evolution stopped producing new traits and started producing features that had already evolved in other lineages. This allowed the researchers to identify the evolutionary “limits” placed on different groups of mammals, showing where they were being excluded from different niches by competition with other animals. The results suggest that it may not have been the dinosaurs that were placing the biggest constraints on the ancestors of modern mammals, but their closest relatives.

The study looked at the anatomy of all the different kinds of mammals living alongside dinosaurs, including the ancestors of modern groups, also known as therians (placentals and marsupials).

By measuring how frequently new features appeared, such as changes in the size and shape of their teeth and bones, and the pattern and timing of their appearance before and after the mass extinction, the researchers determined that the modern mammals were more constrained during the time of the dinosaurs than their close relatives. This meant that while their relatives were exploring larger body sizes, different diets, and novel ways of life such as climbing and gliding, they were excluding modern mammals from these lifestyles, keeping them small and generalist in their habits.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from the University of Oxford in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Mammaliaform extinctions as a driver of the morphological radiation of Cenozoic mammals” by Neil Brocklehurst, Elsa Panciroli, Gemma Louise Benevento and Roger B.J. Benson published in Current Biology.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.