Study Suggests Shift from Lamniform to Carcharhiniform Dominated Shark Populations

The Cretaceous mass extinction event saw the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs on land, but in the seas there was a massive faunal turnover too. For example, many of the marine reptiles became extinct. However, sharks seem to have come through the K-Pg extinction event largely unscathed, but a new study, published in the journal “Current Biology” suggests a subtle change in the diversity of shark species, a change that is reflected in extant shark species today.

Studying Fossil Shark Teeth

The researchers, which include scientists from Uppsala University (Sweden) and the University of New England (Australia), examined hundreds of fossilised shark teeth across the Cretaceous through to the Palaeogene and their study concludes that modern shark biodiversity was triggered by the mass extinction event that took place approximately 66 million years ago.

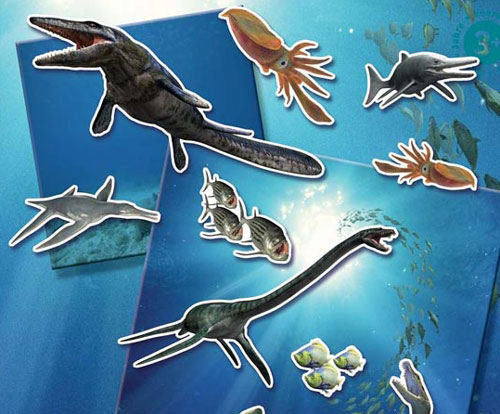

A Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Marine Faunal Assemblage

Picture credit: Julius Csotonyi

Hell’s Aquarium

The Upper Cretaceous marine deposits of Kansas have provided palaeontologists with an insight into the number of large predators that inhabited the sea during the last few million years of the Mesozoic. There were numerous types of mosasaur, such as Hainosaurus which was as long as Tyrannosaurus rex. In addition, you had enormous marine turtles as well as the elasmosaurids, giant plesiosaurs that measured up to fifteen metres in length. Then you have the fish, brutes like Xiphactinus (zie-fak-tin-us) with a mouth lined with needle-sharp teeth and the sharks, lots of species, some of which were apex predators, such as Squalicorax and Cretoxyrhina.

Hell’s Aquarium – Many Different Types of Predator in Late Cretaceous Seas

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Carcharhiniformes and Lamniformes – Two Different Types of Shark

Today, there are two major groups of predatory sharks. Firstly, there are the Carcharhiniformes, otherwise called “ground sharks”, typically represented by species such as the dangerous bull and tiger sharks, as well as the enigmatic hammerhead shark and closer to home, the lesser spotted dogfish (Scyliorhinus canicula) which is resident in British waters. There are around 270 extant species within this clade.

Secondly, there are the Lamniformes, or the “mackerel sharks” which has around fifteen species and includes the great white, mako and another resident of British waters, the Porbeagle shark (Lamna nasus). Back in the Cretaceous, things were very different, the lamniform sharks, in particular, a diverse group of great-white-like sharks, members of the family Anacoracidae, were much more numerous. The fearsome Squalicorax was an anacoracid and therefore along with Cretoxyrhina, members of the Lamniformes clade.

A Model of the Prehistoric Shark Cretoxyrhina

The Cretoxyrhina model (above) is from the PNSO Age of Dinosaurs range.

To view this range: PNSO Prehistoric Animal Figures.

Lead author of the study, PhD student at Uppsala University, Mohamad Bazzi stated:

“Our study found that the shift from lamniform to carcharhiniform-dominated assemblages may well have been the result of the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Unlike other vertebrates, the cartilaginous skeletons of sharks do not easily fossilise and so our knowledge of these fishes is largely limited to the thousands of isolated teeth they shed throughout their lives. Fortunately, shark teeth can tell us a lot about their biology, including information about diet, which can shed light on the mechanisms behind their extinction and survival.”

Fossil Shark Teeth

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Cutting-edge Analytical Techniques

The researchers used state-of-the-art analytical techniques to explore the variation of tooth shape in Carcharhiniformes and Lamniformes and measured diversity by calculating the range of morphological variation, also called disparity.

Dr Nicolás Campione, (University of New England), a co-author of the study added:

“Going into this study, we knew that sharks underwent important losses in species richness across the extinction. But to our surprise, we found virtually no change in disparity across this major transition. This suggests to us that species richness and disparity may have been decoupled across this interval.”

A More Complex Picture

Despite this seemingly stable pattern, the study found that extinction and survival patterns were substantially more complex. Morphologically, there were differential responses to extinction between lamniform and carcharhiniform sharks, with evidence for a selective extinction of Lamniformes and a subsequent proliferation of Carcharhiniformes in the immediate aftermath of the extinction.

Student Bazzi explained:

“Carcharhiniforms are the most common shark group today and it would seem that the initial steps towards this dominance started approximately 66 million years ago.”

Although the reasons for the shift in shark species are not that clear, the researchers hypothesise that the extinction of various types of prey such as the marine reptiles and ammonites may have played a significant role. In addition, it is likely that the loss of apex predators (such as Lamniformes and marine reptiles) benefited secondary predator sharks, a role fulfilled by many carcharhiniforms.

Dr. Campione concluded:

“By studying their teeth, we are able to get a glimpse at the lives of sharks and by understanding the mechanisms that have shaped their evolution in the past, perhaps we can provide some insights into how to mitigate further losses in current ecosystems.”

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Visit Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment