Two New Chinese Dinosaurs Prove Handy

Plotting the Evolution of the Alvarezsauridae with Bannykus and Xiyunykus

A team of international scientists writing in the journal “Current Biology” have published details of two new Chinese alvarezsaurid dinosaurs that will help palaeontologists to better understand the evolution of this group of bizarre theropods. Some later genera becoming the prehistoric equivalents of today’s aardvarks and anteaters. The dinosaurs have been named Bannykus and Xiyunykus and their fossilised bones are proving handy, as palaeontologists seek to understand how the alvarezsaurian dinosaurs reduced and lost most of their digits, except the thumb, which became very large and robust. These sleek, fast-running and very bird-like dinosaurs seemed to have become very specialised over some ninety million years.

Two Newly Described Chinese Dinosaurs Help to Plug an Evolutionary Gap in the Alvarezsauridae

Picture credit: Viktor Radermacher

Chinese Alvarezsaurid Dinosaurs

The Alvarezsauroidea have a long history, basal forms such as Haplocheirus lived in Asia around 160 million years ago and the very last members of the Alvarezsauridae family were present in the Late Cretaceous, a temporal range of at least ninety million years.

The last of these bizarre, very bird-like dinosaurs have been classified into the sub-clade Parvicursorinae and these animals seem to have been very specialised insect eaters, with a strong single thumb digit with an oversized claw, powerful arm and chest muscles (although the length of the arm was much reduced), long snouts, with thin narrow jaws. It has been speculated that these dinosaurs could rip apart the nests of termites or dig into logs to find insects. It has even been suggested that they evolved a long tongue to help them lap up their prey in the same way that an extant anteater does.

The earliest alvarezsaurids were not insectivores, dinosaurs like Haplocheirus were probably hunters of small vertebrates. Haplocheirus (H. sollers), had the teeth of a typical meat-eating theropod and grasping hands to catch prey. Only later alvarezsaurids had much reduced teeth and evolved a hand with a single, large curved thumb claw.

Digit Reduction in Tetrapods

The loss of fingers and toes has occurred numerous times amongst tetrapods. Perhaps the most famous example of all, is the evolution of the foot of the horse. It was the notable American palaeontologist Charles Othniel Marsh, who plotted the evolution of equines by studying the toe bones of ancient horses. Marsh was able to demonstrate how primitive horses gradually lost their toes evolving into the single-toed, fast running animal we know today.

To read more about the contribution of Marsh and the evolution of horses: The Contribution of Othniel Charles Marsh.

Both Bannykus and the slightly smaller Xiyunykus are important because they show transitional steps in the process of alvarezsaurs adapting to new diets.

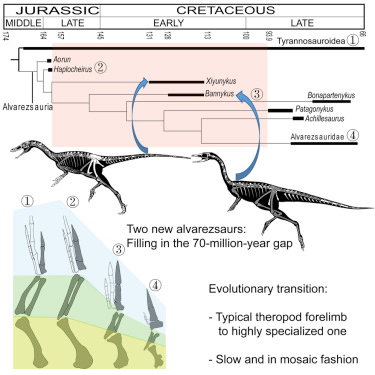

Mapping the Evolutionary History of the Alvarezsauroidea

Picture credit: Current Biology

The image (above) shows the temporal position of the two, newly described species. Both Xiyunykus and Bannykus lived during the Early Cretaceous, their fossils are helping to bridge a seventy million year gap between Late Jurassic basal forms and the advanced and highly specialised Late Cretaceous forms.

Xiyunykus pengi

Xiyunykus was the first of these new dinosaurs to be discovered. Its fossils were found in 2005, by an international expedition to the Junggar Basin (Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of north-western China). The fossil remains consist of a partial, disarticulated skeleton and the material has been dated to the Barremian-Aptian faunal stages of the Early Cretaceous. The researchers, including Xu Xing from the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology (IVPP) have estimated that this dinosaur weighed around fifteen kilograms.

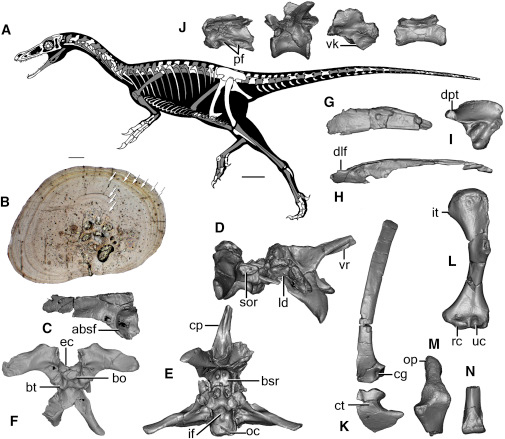

Skeletal Remains of Xiyunykus pengi

Picture credit: Current Biology

A cross-sectional analysis of lower leg bone (B) in the image above, indicates that this dinosaur was around nine years of age when it died and probably a sub-adult. The genus name is from “Xiyu”, the Mandarin for denoting the western regions of Central Asia and from the Greek “onyx” meaning claw. The trivial name honours Professor Peng Xiling, who has played a significant role in the study of the geology of this region.

Bannykus wulatensis

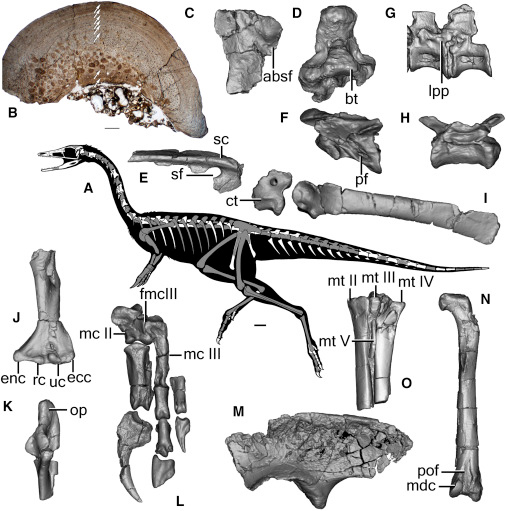

The second alvarezsaurid was discovered in 2009 in western Inner Mongolia. The fossils come from the Bayingobi Formation (Aptian faunal stage of the Early Cretaceous). Histological analysis of a cross-section of bone taken from the fibula indicates that this dinosaur was around eight years of age when it died. It, like the Xiyunykus specimen, was probably a sub-adult.

Skeletal Remains of Bannykus wulatensis

Picture credit: Current Biology

The genus name comes from the Mandarin “Ban” meaning half, a reference to the transitional anatomical features seen in this dinosaur and “onyx”, from the Greek for claw. The trivial name refers to Wulatehouqi (Wulate Rear Banner), the county-level administrative division in which the type locality is situated.

Long Arms and Grasping Hands to Reduced Arms and Digits

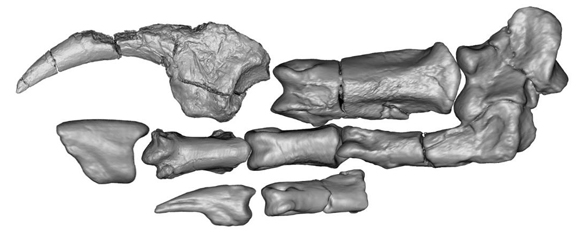

These two newly described Alvarezsaurian dinosaurs have helped to determine that these peculiar Theropods very probably originated in Asia, before migrating to other parts of the world such as North and South America over their long evolutionary history. Bannykus and Xiyunykus are important because they show transitional steps in the process of alvarezsaurs adapting to new ecological niches, Bannykus, which may have lived slightly later than Xiyunykus, is showing signs of that mechanically efficient forearm, a more robust and powerful upper arm and an enlarged thumb.

The Manus (Hand) of Bannykus Showing a Transitional Stage in Alvarezsaurid Evolution

Picture credit: Current Biology

Still a Puzzling Group of Bird-like Dinosaurs

The discovery and scientific description of these new members of the Alvarezsauridae is very significant. These fossils will help scientists to better understand the evolution of the specialised hand of alvarezsaurids and provide assistance when it comes to phylogenetic placement for group members.

Lead author of the scientific paper, Xu Xing commented on the evolutionary changes that had been highlighted stating:

“This transition plays out in an incremental fashion over more than 50 million years. It could one day potentially serve as a classic example of macroevolution akin to the ‘horse series’ of North America.”

These dinosaurs are some of the more bizarre and peculiar forms of theropod. Ancestral forms seemed to have anatomical features quite typical of carnivorous dinosaurs, before evolving much more specialised forms, probably in response to exploiting a particular ecological niche.

Co-author James Clarke (George Washington University), added:

“The fossil record is the best source of information about how anatomical features evolve and like other classic examples of evolution such as the “horse series,” these dinosaurs show us how a lineage can make a major shift in its ecology over time.”

Chinese Alvarezsaurid Dinosaurs – A Puzzle

The alvarezsaurian dinosaurs remain a puzzle. They may have evolved into specialist insectivores, but they retained their long legs and the ability to run fast throughout their evolutionary history. The forelimbs, hands and digits may have undergone a radical change, but these dinosaurs always seem to have remained quite graceful and agile animals.

Why these animals retained their ability to run very quickly when their prey was to be found in a termite mound or a rotting log is not clear. However, it is likely, that the ability to run fast was continued to be selected for in this group as an adaptation to avoiding being eaten by larger predatory dinosaurs.

Palaeontologists Xu Xing and James Clarke Searching for Dinosaur Fossils

Picture credit: Xu Xing

The scientific paper: “Two Early Cretaceous Fossils Document Transitional Stages in Alvarezsaurian Dinosaur Evolution” by Xing Xu, Jonah Choiniere, Qingwei Tan, Roger B.J. Benson, James Clark, Corwin Sullivan, Qi Zhao, Shuo Wang, Hai Xing and Lin Tan published in Current Biology.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.