A Challenge to the Aquatic Spinosaurus Theory

Was Spinosaurus aegyptiacus at Home in the Water?

New research utilising computer modelling to study the buoyancy of Spinosaurus (S. aegyptiacus) by Dr Donald Henderson of the Royal Tyrrell Museum (Alberta, Canada), challenges the idea that this sail-backed theropod was adapted for a semi-aquatic way of life.

The research suggests that Spinosaurus could float and keep its head clear of the water to enable it to breathe, but other theropods could also float in positions that enabled them to breathe freely, but with its pneumatised skeleton and system of air sacs, diving for food was probably beyond Spinosaurus, thus hindering its ability to be an effective semi-aquatic, pursuit predator. Dr Henderson concludes that Spinosaurus may have been more at home wading through water, specialising in hunting along the shoreline or in shallow water, but still remaining a competent terrestrial predator.

Spinosaurus May Have Been a Shallow Water or Shoreline Predator

Picture credit: BBC

Challenging the 2014 Scientific Paper

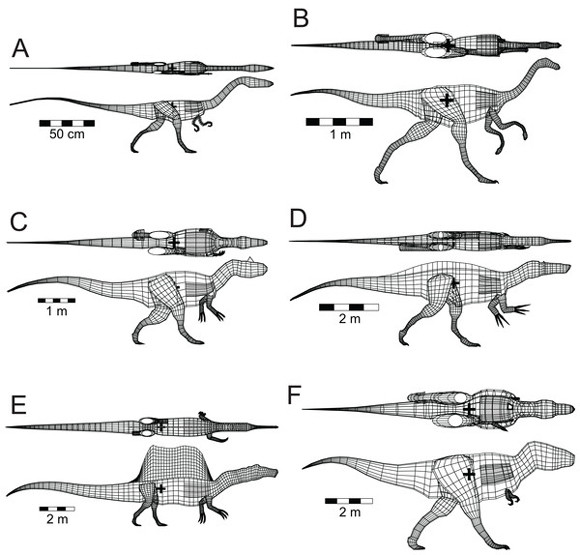

Dr Henderson set about creating three-dimensional computer models of Spinosaurus and several other theropods including Allosaurus, Coelophysis, the ornithomimid Struthiomimus, Tyrannosaurus rex and another member of the Spinosauridae family – Suchomimus tenerensis. Dr Henderson, who is the Curator of Dinosaurs at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, located in Drumheller, southern Alberta, wanted to test the hypothesis proposed by Dr Nizar Ibrahim and colleagues published in September 2014, that hypothesised that S. aegyptiacus was quadrupedal and a semi-aquatic dinosaur, a first for a member of the Theropoda.

To read Everything Dinosaur’s article about the 2014 scientific paper: Spinosaurus – Four Legs are Better than Two.

Intriguingly, the interpretation of Spinosaurus, as proposed by Ibrahim et al, was used as the basis for the digital Spinosaurus model by the Royal Tyrrell Museum researcher.

Views of the Theropod Body Plans Used to Test Buoyancy

Picture credit: PeerJ/Dr Henderson (Royal Tyrrell Museum)

The picture above shows the digital body plans used to test the theoretical buoyancy of different types of theropod dinosaur.

Key

A). Coelophysis bauri

B). Struthiomimus altus

C). Allosaurus fragilis

D). Suchomimus tenerensis (Baryonyx tenerensis) – it has been suggested that Suchomimus and Baryonyx fossil material might represent the same genus (Holtz, 2012; Sues et al., 2002), this conclusion was used in this study.

E). Spinosaurus aegyptiacus – the body plan based on the body shape proposed by Ibrahim et al in the 2014 paper.

F). Tyrannosaurus rex

Testing Buoyancy in Freshwater

To ensure that the digital models were able to replicate the orientation and depth of immersion in freshwater, Dr Henderson tested the software using a model of an alligator (A. mississippiensis). Furthermore, he assessed the buoyancy of a computer generated model of an emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri), which is also a member of the theropoda.

Dr Henderson explained:

“Science is self-correcting. Research is a competitive scientific process that continually generates new information and ideas, so here’s some of the self-correcting in action.”

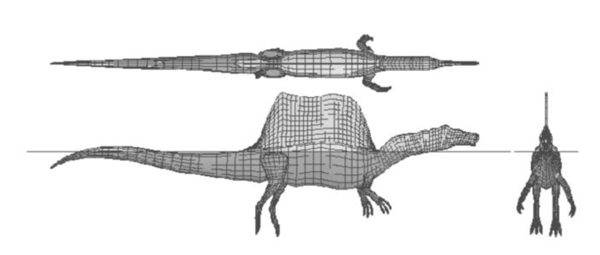

Testing the Stability and Buoyancy of Spinosaurus (S. aegyptiacus)

Picture credit: PeerJ/Dr Henderson (Royal Tyrrell Museum)

Spinosaurus Could Float But So Could Other Theropods

Dr Henderson’s digital models demonstrated that Spinosaurus could indeed float with its head above water, enabling it to breathe freely. However, the models of other theropod dinosaurs demonstrated similar results. This was not unexpected as most tetrapods can successfully float and swim, the shape of Spinosaurus did not necessarily give it an advantage over the body shape of other dinosaurs when it came to stability in water.

Alligators Much Better Suited to Water Than Spinosaurus

The stability of a Spinosaurus in freshwater was also compared to the digital alligator. When tipped to the side, the alligator model returned to its original topside position. Such behaviour is seen in semi-aquatic animals, they have the ability to right themselves when floating. The Spinosaurus model did not perform well in the same tests. When tilted, the model rolled over onto its side, demonstrating very little lateral stability in water. The research implies that Spinosaurus would have easily tipped over and would have had to use its limbs constantly to maintain an upright posture in the water.

Assessing the Centre of Mass

One of the key points of the 2014 paper, was that an anatomical study based on the known Spinosaurus fossil material (which represented numerous individuals of different sizes), indicated that this dinosaur walked on all fours.

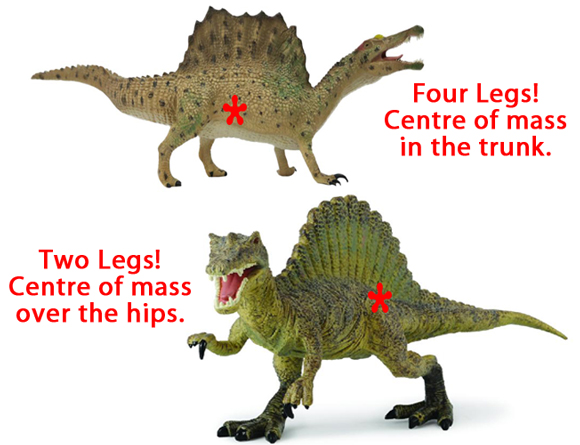

In this new research, the centre of mass of the digital model of Spinosaurus was found to be close to the hips, similar to what is seen in other theropods. This contradicts the 2014 research, as Dr Ibrahim and his colleagues proposed that S. aegyptiacus had a centre of mass located towards the centre of the torso. With the centre of mass located further forward, it suggests a quadrupedal form of locomotion, however, Dr Henderson’s research indicating a centre of mass positioned over the hips suggests that Spinosaurus could have walked around on land quite happily on just its hind legs (bipedal).

The Position of the Centre of Mass Would Affect Locomotion on Land

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The models featured in the image above are from the CollectA Deluxe range.

To view this range of prehistoric animal models: CollectA Deluxe Prehistoric Life Models.

Spinosaurus Probably Couldn’t Dive

Dr Henderson’s models also found Spinosaurus to be unsinkable. Living aquatic birds, reptiles, and mammals all have the ability to submerge themselves to pursue their prey underwater. Although the bones of Spinosaurus might be more dense than other carnivorous dinosaurs, they still were substantially pneumatised. This anatomical feature in conjunction with the air sac breathing system found in living theropods (birds), probably made it very difficult, if not impossible, for this dinosaur to dive underwater in search of prey.

Dr Henderson concludes that this inability to dive, combined with a centre of mass close to the hips and a tendency to roll onto its side, suggests that Spinosaurus was not a specialised semi-aquatic predator after all.

He added:

“Spinosaurus may have been specialised for a shoreline or shallow water mode of life, but it would have still have been a competent terrestrial animal.”

Few Spinosaurus Bones to Study

However, as there are so very few Spinosaurus fossil bones to study, it is possible that this dinosaur lacked a significant number of avian style air sacs and pneumatised bones. Even with an increased mass offered by a denser skeleton the digital model when “tweaked” in this way, still suggested that being able to submerge and go underwater would have been a considerable challenge. Dr Henderson does concede that if it could be shown that the mass deficit represented by the lungs and air sacs was offset by the increased mass of a denser skeleton that might help the claim of a semi-aquatic Spinosaurus.

This is essentially, the central point of the Spinosaurus controversy. This dinosaur did live in a habitat dominated by large bodies of water. There were plenty of large fish around for an aquatic predator to eat, but in the absence of fossil evidence, the actual role of Spinosaurus in the North African Cretaceous ecosystem and its habits remain very much open to debate.

The scientific paper: “A Buoyancy, Balance and Stability Challenge to the Hypothesis of a Semi-aquatic Spinosaurus Stromer, 1915 (Dinosauria: Theropoda)” by Donald M. Henderson and published in the academic on-line journal PeerJ.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.