New Study Looks at the Growth Rates of Polar Hypsilophodonts

Researchers from Museums Victoria (Melbourne, Australia) and the Oklahoma State University Centre for Health Studies, have published a new paper in the academic journal “Scientific Reports” that examines the growth rates of polar dinosaurs, specifically the growth rates of those fleet-footed ornithischians the hypsilophodontids. Palaeontologists have long-debated whether these small dinosaurs, which were geographically widespread during the Early Cretaceous, showed different growth rates between high latitude forms and those that lived closer to the Equator.

An Illustration of a Typical Hypsilophodont Dinosaur

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The Perils of Being a “Polar” Dinosaur

Dinosaurs that lived in high latitude habitats such as those that lived on the southernmost portions of Gondwana, had to endure low temperatures, plus periods of prolonged darkness as the sun dropped below the horizon. Although, nowhere near is as cold as the Antarctic today, close to the South Pole in the Early Cretaceous was quite a foreboding, formidable environment. However, several types of non-avian dinosaurs, including several hypsilophodonts seem to have flourished. Four taxa have been described to date, from two principle locations namely:

- Fulgurotherium australe from the Flat Rocks and Dinosaur Cove locations (Victoria)

- Qantassaurus intrepidus (Flat Rocks location)

- Leaellynasaura amicagraphica from Dinosaur Cove

- Atlascopcosaurus loadsi (Dinosaur Cove)

As all these genera are named from fragmentary remains (elements from the jaw and individual teeth), with the exception of L. amicagraphica, which is known from more substantial material, in the absence of more fossil remains some of these taxa are regarded as nomen dubia.

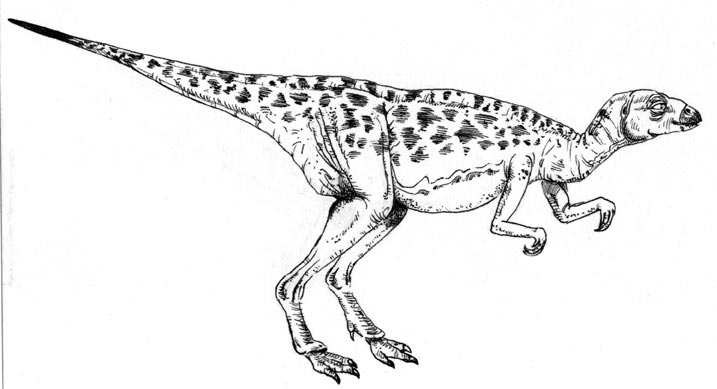

The microstructure of limb bones (femora and tibias) were analysed to identify growth trends, the study revealed that there were probably two genera present in those fossils studied which had come from Dinosaur Cove. Bone microstructure alone, could not distinguish taxa within the sample of bones from the Flat Rocks area. The researchers, which included Dr Thomas Rich and his partner Dr Patricia Vickers-Rich conclude that further histological study of hypsilophodont material from these sites may help to confirm the number of genera present as well as to help improve the data on polar dinosaur growth rates. Leaellynasaura was named in honour of the couple’s daughter Leaellyn Rich.

Several Hypsilophont Species Likely

Flat Rocks and the Dinosaur Cove locations are separated by Port Phillip Bay, they are approximately 120 miles (200 kilometres) apart. These areas are also distant from a geological perspective, with the Flat Rocks locality being made up of sedimentary rocks that date from around 133 – 128 million years ago (Late Valanginian or Barremian faunal stages of the Early Cretaceous).

Whereas, the rocks that formed Dinosaur Cove on the other side of Cape Otway, are much younger, being laid down approximately 106 million years ago (Albian faunal stage of the Early Cretaceous). Based on the temporal range that these fossils represent, then it is quite likely that these dinosaur fossils from the coast of Victoria do, indeed, represent several genera.

Growth Rates Amongst Polar Hypsilophodonts

The research into the bone microstructure of the limb bones of these types of polar dinosaur reveals that both the Flat Rocks and Dinosaur Cove specimens were growing in a similar way, at a similar rate to many typical small-bodied vertebrates. These animals tended to have lower annual growth rates when compared to larger vertebrates.

The palaeontologists note that the large (eight metres long), ornithischian Maiasaura from the Late Cretaceous of the United States took around eight years to reach adult size, whereas one of the specimens in the study seems to have reached maturity a year earlier, but it was a much smaller-bodied dinosaur, only growing at a fraction of the rate of the larger Maiasaura.

Transverse Sections from the Femur of a Hypsilophodont Used in the Study

Picture credit: Scientific Reports

A Slow Growth Rate

The researchers did note that although the polar hypsilophodontids grew quite slowly compared to their larger relatives, the bone histology studies revealed that they had a relatively elevated growth rate for the first few years of their life. Growing up relatively quickly, or at least reaching a certain threshold body size could have been an evolutionary response to avoid predation.

The paper published in “Scientific Reports”, is the first study of its kind into the growth rates of Australian polar hypsilophodonts. The team conclude that these dinosaurs might have reached maturity in about five to seven years. As adults, these genera only rarely exceeded lengths of 2.8 metres, most of which was tail and individual body mass for most of these dinosaurs was under fifty kilograms.

The research could be extended to include an analysis of hypsilophodontid limb bones excavated from lower latitudes. A more complete comparison between the ontogeny of hypsilophodonts from different parts of the world could then be made.

Visit the website of Everything Dinosaur: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment