The Tale of the Spiders with Tails

Prehistoric Spiders Had Tails

A team of international scientists, including researchers from the University of Manchester, have announced the discovery of a new species of Cretaceous-aged spider. The arachnid (Class Arachnida), which was preserved in amber from Myanmar (burmite), is helping palaeontologists to better understand the evolution of these very successful and diverse, eight-legged invertebrates. This new spider species, named Chimerarachne yingi possessed a whip-like tail, a characteristic associated with ancestral forms and the most primitive types of extant spider, but the burmite has preserved a spider with this characteristic, that lived at least 250 million years after the first spiders evolved.

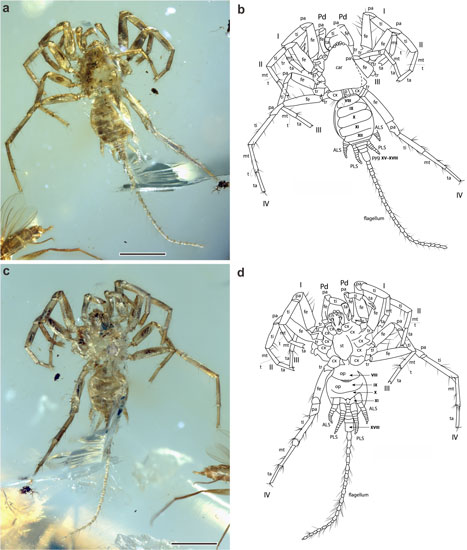

Photographs of the Spider Fossil with Accompanying Line Drawings

Picture credit: The University of Manchester

Chimerarachne yingi – Potentially a Transitional Fossil

The characteristics of today’s spiders are very well known. These creatures have eight legs, several eyes and can spin silk, often to create cobwebs. A “whip-like tail” is one feature that you would not normally associate with these particular creepy-crawlies. The researchers, writing in the academic journal “Nature Ecology and Evolution”, conclude that the specimen might represent a transitional fossil, it possesses a tail (flagellum) and as such, the fossil may help scientists to better understand how the Arachnida evolved and diversified.

What is a Transitional Fossil?

Transitional fossils are defined as any fossil that demonstrates traits that are common to both an ancestral group and descendants. Perhaps the best-known example is Archaeopteryx lithographica from the Late Jurassic of southern Germany. The “Urvogel” shows both reptilian traits and characteristics of a bird, so it is regarded as a transitional fossil highlighting the evolution of one part of the Theropoda into modern Aves (birds).

A Fossil of the “Urvogel” Archaeopteryx Regarded as a Transitional Form

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Chimerarachne yingi

The genus name comes from the Greek chimera – a mythical beast that was made up of parts from numerous animals. The research team conclude that this new species belongs to an extinct group of spiders which were very closely related to true spiders. What makes the fossil so unique, and different to spiders of today, is the fact it has a tail. The discovery sheds important light on where modern spiders may have evolved from.

The Arachnida is an extremely successful class of invertebrates. Spiders are the most diverse and numerous of all the arachnids, together spiders are grouped into the Order Aranae, some 47,000 living species have been documented. Their evolutionary origins are obscure, but the first spiders may have evolved in the Late Devonian. Over hundreds of millions of years, they have evolved several key innovations found only in this group. These include spinnerets for producing silk for webs (as well as for other purposes like egg-wrapping), modified male mouthparts (pedipalps), unique to each species, which are used to transfer sperm to the female during mating, and venom for paralysing prey.

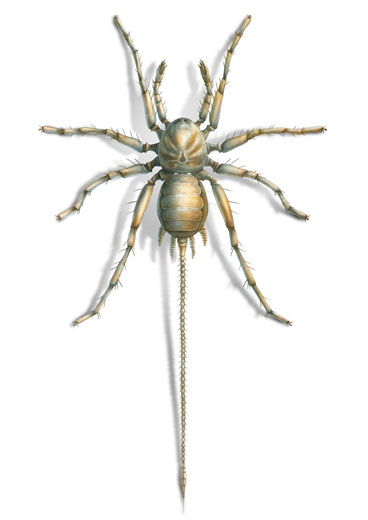

An Illustration of the Newly Described Cretaceous Arachnid Chimerarachne yingi

Picture credit: The University of Manchester

The researchers, led by Bo Wang from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and including Dr Russell Garwood (University of Manchester), state that Chimerarachne yingi closely resembles a member of the most primitive group of modern living spiders – the mesotheles. These spiders have a segmented abdomen unlike other groups found today, such as the mygalomorphs (Mygalomorphae), which include well-known spider species like tarantulas and funnel-webs. Mesothelae spiders are restricted to south-east Asia, China and Japan today, but in the past they probably had a world-wide distribution (across the ancient super-continent of Pangaea).

Several Important Spider Characteristics

Chimerarachne yingi has several important spider features such as the spinnerets and a modified male pedipalp, but, outside of the obvious tail, it also demonstrates some anatomical differences. For instance, the male pedipalp organ of Chimerarachne appears quite simple, more like that of a mygalomorph spider than a mesothele spider.

Note the Long “Whip-like Tail” (Flagellum)

Picture credit: The University of Manchester

Dr Garwood explained:

“Based on what we see in mesotheles, we also would have expected the common ancestor of spiders alive today to have had four pairs of spinnerets, all positioned in the middle of the underside of the abdomen. Chimerarachne only has two pairs of well-developed spinnerets, towards the back of the animal, and another pair that is apparently in the process of formation.”

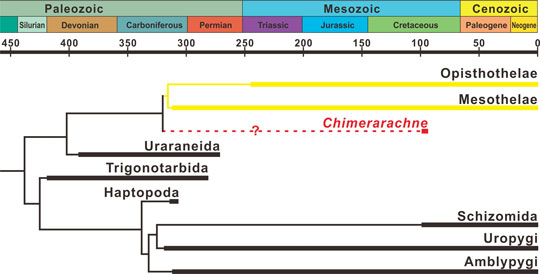

Working Out the Evolutionary Tree of the Arachnida

The team studied the fossil using a range of different techniques. One of Dr Garwood’s roles in the study was to help work out where this fossil sits in the evolutionary tree of the Arachnida.

Dr Garwood added:

“Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the new fossil is the fact that more than 200 million years after spiders originated, close relatives, quite unlike arachnids alive today, were still living alongside true spiders.”

Despite the beautiful state of preservation, the scientists are unable to state what function the tail might have had, or indeed, if this spider had a venomous bite.

Co-author of the study, published today, Dr Jason Dunlop (Museum Für Naturkunde in Berlin) stated:

“We don’t know whether Chimerarachne was venomous. We do know that the arachnid ancestor probably had a tail and living groups like whip scorpions also have a whip-like tail. Chimerarachne appears to have retained this primitive feature. Taken together, Chimerarachne has a unique body plan among the arachnids and raises important questions about what an early spider looked like, and how the spinnerets and pedipalp organ may have evolved.”

A Timescale Outlining the Proposed Evolution of the Chimerarachne

Picture credit: The University of Manchester

Despite its appearance, the research team have concluded that C. yingi is not a direct ancestor of modern day spiders. Spider fossils, although very rare, go back a long way into deep geological time. Instead Chimerarachne belongs to an extinct lineage of spider-like arachnids which shared a common ancestor with the spiders, some of whom survived into the mid-Cretaceous of Southeast Asia.

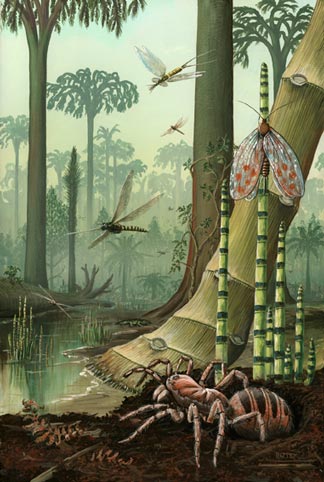

By the Late Carboniferous Arachnids Represented a Diverse and Important Group of Terrestrial Predators

Picture credit: Richard Bizley

The scientific paper: “Cretaceous Arachnid Chimerarachne yingi et sp. nov. Illuminates Spider Origins”, by Wang, B., Dunlop, J. A., Selden, P. A., Garwood, R. J., Shear, W. A., Müller, P. & Lei, X published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of the University of Manchester in the compilation of this article.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.