Ancient Butterflies, Flutter By as New Research is Published

Fossilised Wing Scales Provide Evidence of Triassic Moths and Butterflies

Butterflies and moths might be regarded as delicate creatures, what with the diaphanous wings and light-weight bodies, but a new study published in the journal “Science Advances” suggests that the Lepidoptera have been around for many millions of years longer than previously thought. The new fossil discoveries, made by an international team of scientists led by Timo van Eldijk and Bas van de Schootbrugge (Utrecht University), have also challenged the presumed co-evolution between flowering plants (angiosperms) and pollinating insects.

Triassic Moths and Butterflies

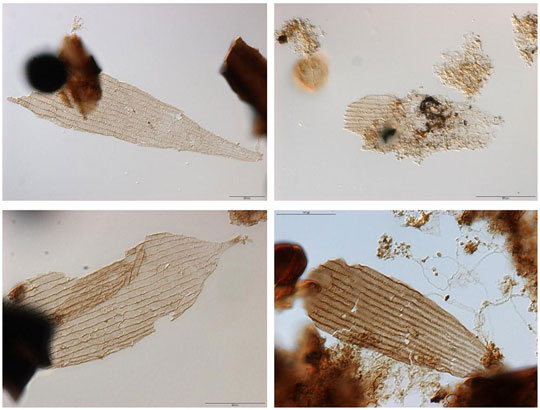

Fossil Evidence for Ancient Moths and Butterflies

Picture credit: University of Utrecht

A core drilled into sediments in Schandelah, Lower Saxony (northern Germany), revealed microscopic wing scales some 70 million years older than the oldest, confirmed fossils of flowering plants. The team’s findings suggest that wing and body scales found in rocks some 201 million years old, provide evidence that the Lepidoptera survived the end-Triassic mass extinction event. Indeed, like the Dinosauria, moths and butterflies may have benefited from the extinction event, being able to exploit environmental niches vacated by extinct species.

Drilling into Ancient Rocks Triassic/Jurassic Strata

Picture credit: University of Utrecht/Dr Bas van de Schootbrugge

Commenting on the significance of the core drill study, Utrecht University student Timo van Eldijk explained:

“The mass extinction event occurred at the end of the Triassic and was associated with massive volcanism as the super continent Pangaea started to break apart. As a result, biodiversity on land and in the oceans suffered a setback with many key Triassic species going extinct, including many primitive reptiles. However, one major group of insects, the Lepidoptera, moths and butterflies, appeared unaffected. Instead, this group diversified during a period of ecological turnover.”

The Moth and Butterfly “Tongue”

Extant butterflies and moths have a well-known association with flowering plants. As they feed on the nectar with their long proboscis (an elongated, sucking mouthpart), they pick up pollen and therefore play an important role in angiosperm reproduction.

Dr Bas van de Schootbrugge (Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University) stated:

“The fossil remains contain distinctive hollow scales and provide clear evidence for a group of moths with sucking mouthparts, which is related to the vast majority of living moths and butterflies.”

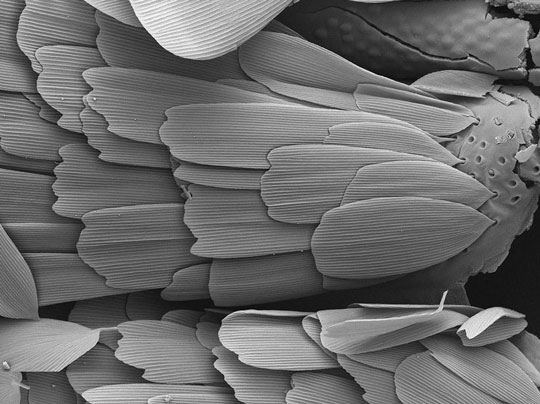

A Scanning Electron Microscope Image of the Wing Scales on an Extant Moth Species

Picture credit: University of Utrecht

What Did the Triassic Lepidoptera Feed On?

If there were moths and butterflies about some 201 million years ago, some 70 million years before the first flowering plants, then what were the adult animal’s feeding on? The researchers conclude that the first lepidopterans were feeding on non-flowering seed plants (gymnosperms), one of the most successful plant groups of the early Mesozoic. The earliest proboscid moths (Glossata), likely used their long, sucking mouthparts to feast on the sugary pollination beads secreted by several groups of gymnosperms.

There is another tantalising and very controversial aspect that is worth considering. What if the flowering plants evolved much earlier than previously thought?

In 2013, Everything Dinosaur published an article providing information on some intriguing research that suggested flowering plants originated more than 240 million years ago, in the Early Triassic. If flowering plants were around over 100 million years earlier than previously thought than a symbiotic relationship between early Lepidoptera and early angiosperms could have already been in place.

To read the article about evidence for Lower Triassic flowering plant fossils: Saying it with Flowers 100 Million Years Before Anyone Expected.

On the basis of the fossilised wing and body scales recovered from Upper Triassic and Lower Jurassic sediments, the scientists have provided the earliest evidence to date for moths and butterflies. The diversity of the scales found confirm a Late Triassic radiation of lepidopteran forms, including the divergence of the Glossata, a clade that consists of the living butterflies and moths with a sucking proboscis. The team conclude that the early evolution of the Lepidoptera was probably not severely interrupted by the end-Triassic mass extinction event.

Providing an Insight into Today’s Climate Change

MSc student Timo Van Eldijk stated:

“This evidence has transformed our understanding of the evolutionary history of moths and butterflies as well as their resilience to extinction. By studying how insects and their evolution was affected by dramatic greenhouse warming at the start of the Jurassic, we hope to provide insight into how insects might respond to the human-induced climate change challenges we face today.”

An Example of an Extant Member of the Glossata Clade

Picture credit: Hossein Rajaei/Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart (Stuttgart, Germany)

The scientific paper: “A Triassic-Jurassic Window into the Evolution of Lepidoptera” by Timo van Eldijk, Torsten Wappler, Paul Strother, Carolien van der Weijst, Hossein Rajaei, Henk Visscher and Bas van de Schootbrugge, published in the journal “Science Advances”.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from the University of Utrecht in the compilation of this article.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.