Giant Ordovician Filter Feeder Provides Important Clues to Arthropod Evolution

Two Metre Long Aegirocassis benmoulae Expands Ecological Role of Anomalocarids

A beautifully preserved fossil of a giant arthropod from Morocco is helping palaeontologists to gain a better understanding of the evolution and the development of the arthropoda as well as providing a new perspective on the fauna that formed an extensive and diverse ecosystem in an Early Ordovician sea.

The Arthropoda

The Arthropoda are the largest phylum in the Kingdom Animalia and the first fossils of these segmented creatures with their hard, external skeletons date from the Early Cambrian. Characteristics of these animals include that exoskeleton, a segmented body plan and paired, jointed appendages that can perform a variety of functions, such as swimming, walking and feeding. Typical arthropods include crustaceans, spiders, king crabs, scorpions, mites and insects, all very familiar to us today. Extinct forms include the Trilobita and the anomalocarids, one of which turns out to be a two-metre-long giant that fed like a baleen whale.

A team of researchers including scientists from Yale University and the University of Oxford have been examining the three-dimensional remains of this strange, new type of anomalocarid in a bid to understand how the arthropods diversified and those highly adaptable paired, jointed appendages first evolved. It could be argued that it is the arthropods that dominate animal life on our planet. As a phylum they have adapted to a huge range of different habitats and they make up over eighty percent of all described animal species. Enter into the debate, a newly described anomalocarid named Aegirocassis benmoulae.

The Anomalocarididae Family

The Anomalocarididae family are long-extinct. However, they are regarded as basal members of the Arthropoda and their fossil record extends from the Cambrian into possibly the Devonian, although Devonian anomalocarids remain a controversial area of palaeontology due to differing interpretations of fossil material. These marine creatures grew to very large sizes in relation to other marine fauna and the majority of them were nektonic predators. However, A. benmoulae evolved in a very different direction.

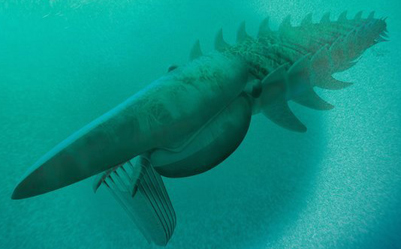

An Illustration of the Giant Aegirocassis benmoulae – Filter Feeder of the Early Ordovician

Picture credit: Marianne Collins, ArtofFact

Unlike Any Living Animals

The anomalocarids were like no living animal today. The mouth was circular on the underside of the head and surrounded by frightening, jagged (in most cases) hard tooth plates, designed for crushing the exoskeletons of other arthropods. The large, compound eyes gave these active hunters an excellent all-round field of vision and at the front of the head was a pair of spiny, grasping appendages used to grab prey. Their elongated, segmented bodies had flaps on the side that were used for propulsion. Until the discovery of A. benmoulae it had been believed that anomalocarids had only one set of flaps per body segment and that they had completely lost their walking legs.

The fossils, which have been preserved in three dimensions, an extremely rare preservation state for an arthropod, come from the Draa valley in south-east Morocco. The sediments were formed at the bottom of a deep sea and the strata has provided palaeontologists with an insight into life in the Early Ordovician. Very occasionally violent storms disturbed the seabed and buried large numbers of animals. These events led to the formation of a very rich Lagerstätten, which has helped scientists to map the pace of evolution from the Cambrian explosion some sixty million years before these fossils formed to the end of the Ordovician some 443 million years ago.

The fossils from this part of Morocco form the Fezouata Biota, representing a marine habitat dating from around 485-480 million years ago.

To read about the discovery of a giant, predatory anomalocarid from the same region of Morocco: Giant Marine Predator of the Ordovician.

Aegirocassis benmoulae

The description of Aegirocassis benmoulae provides new evidence for Arthropoda evolution. The exquisite preservation reveals that anomalocaridids had in fact, two separate sets of flaps per segment. The upper flaps equate to the upper limb branch of modern Arthropods, while the lower set of flaps represent modified walking limbs that were adapted for swimming. A reassessment of older anomalocarid fossilised remains also show two separate flaps per body segment. The scientists have concluded that the anomalocaridids represent a stage of Arthropoda evolution before the fusion of the upper and lower appendages that form the double-branched limbs of extant arthropods.

Peter Van Roy, an associate research scientist (Yale University) and an authority on the Fezouata Biota stated:

“It was while cleaning the fossil that I noticed the second, dorsal set of flaps. It is fair to say I was in shock at the discovery and its implications. It once and for all resolves the debate on where anomalocaridids belong in the arthropod tree and clears up one of the most problematic aspects of their anatomy.”

The Adaptable Arthropoda

As if to reflect the adaptability of the Arthropoda bauplan, it seems that this Moroccan giant evolved to exploit the abundance of small marine organisms that flourished in the Early Ordovician. The head appendages that formed the spiky, grasping claws of this anomalocarid became modified into delicate filter feeding apparatus. It is likely that this creature cruised the oceans feeding on tiny plankton and other organisms floating on the currents just like modern baleen whales, manta rays and whale sharks.

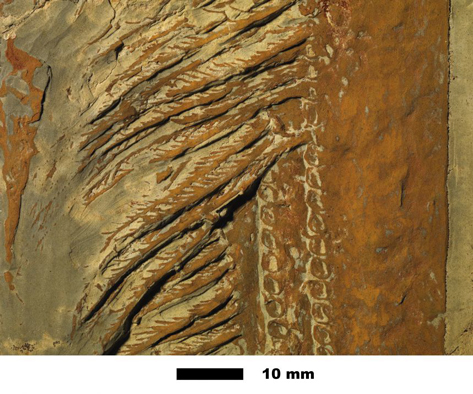

A Close up Showing the Delicate “Fronds” of the Filter Feeding Net

Picture credit: Peter Van Roy (Yale University)

The picture shows a close up of the prepared fossil material showing the delicate fronds which the creature used to sieve sea water for food (scale bar = 10 mm).

Filling an Ecological Role

Commenting on the implications for Early Ordovician ecosystems, co-author of the scientific study, Dr Allison Daley (Oxford University’s Department of Zoology) stated:

“These animals are filling an ecological role that hadn’t previously been filled by any other animal. While filter feeding (filtering water to find food) is probably one of the oldest ways for animals to find food, previous filter feeders were smaller, and usually attached to the sea-floor [benthic]. We have found the oldest example of gigantism in a freely swimming filter feeder.”

Everything Dinosaur stocks a variety of invertebrate replicas, models of iconic fossil animals including important arthropods. To view the range available: CollectA Prehistoric World/Prehistoric Life.