Dinosaur Tracks from Alaska Reveals Herd Structure of Edmontosaurs

Thousands of dinosaur footprints discovered in Alaska have provided palaeontologists with the first definitive guide to the herd structure of Late Cretaceous duck-billed dinosaurs. The fossil site location is within the boundaries of Denali National Park and it represents one of the greatest concentrations of dinosaur tracks ever discovered. The site provides evidence that at least four different sizes of the same species lived together in a herd and it supports the theory that dinosaurs lived at high latitudes all year round.

Dinosaurs at High Latitudes

The tracksite was discovered back in the summer of 2007 by a field team led by a trio of palaeontologists, Dr Anthony Fiorillo (Perot Museum of Nature and Science, Dallas), Dr Yoshitsugu Kobayashi (Hokkaido University Museum, Japan) and Dr Stephen Hasiotis (University of Kansas), an academic paper detailing the discovery has just been published in the journal “Geology”. The actual fossil site is being kept a closely guarded secret but the strata is part of the Upper Cretaceous Cantwell Formation.

Commenting on the discovery, lead author of the scientific paper, Dr Fiorillo stated:

“Without question, Denali is one of the best dinosaur footprint localities in the world, but what we found was incredible, so many tracks, so big and so well preserved. Many had skin impression so we could even see what the bottom of their feet looked like. And there were lots of invertebrate traces, the tracks of bugs, worms, larvae and more, which were important to us because they showed an ecosystem existed during the warm parts of the year.”

An Illustration Depicting the Late Cretaceous of Alaska

Picture credit: Karen Carr

Edmontosaurus

The picture above depicts an imagined summer scene in the Late Cretaceous of Alaska. A herd of Edmontosaurus (duck-billed dinosaurs) wade across a body of water, whilst a tyrannosaur ambushes a group of these herbivores, on the left of the scene, a giant therizinosaur looks on. A flock of azhdarchid pterosaurs soars overhead.

Dr Fiorillo and his colleagues from the Perot Museum of Nature and Science have been at the fore front of studies into Alaskan dinosaurs. As well as exploring the fossilised trackways, the Dallas based scientists have helped with the documentation of a new species of Alaskan pachyrhinosaur and provided footprint evidence to suggest that therizinosaurs roamed this far north.

To read an article about the discovery of a fossilised footprint from a potential therizinosaur: Is this Evidence for an Alaskan Therizinosaur?

Five Exposed Bedding Planes

The fossil site, was believed to represent as many as five exposed bedding planes when it was initially examined but a number of summer expeditions were able to map the area and identify this location as a single bedding plane preserving the footprints made by several types of dinosaur as they wandered close to a large body of water, either a slow moving river or possibly a large lake. The vast majority of the footprints are those made by duck-billed dinosaurs, as fossilised remains of Edmontosaurus have been found in this part of the world, it has been assumed that the tracks were made by a herd of Edmontosaurus dinosaurs.

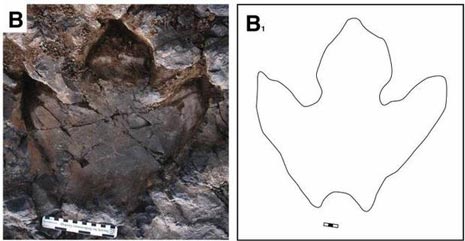

A Close Up of One of the Fossilised Plant-Eating Dinosaur Footprints

Picture credit: Perot Museum of Nature and Science

The picture shows B an in situ photograph of a single footprint with its associated line drawing (B1).

Aerial Photographs and Pictures that Provide an Overview of the Fossil Site

Picture credit: Perot Museum of Nature and Science

The picture above shows various black and white views of the location. The large photograph in the centre is a view of the Denali National Park tracksite from the air. Picture B shows the left side of the trackway with each dimple in the shot representing a single footprint. Picture C shows a typical hadrosaur track at the site, whilst D shows hadrosaur footprints from the right side of the fossil site.

Different Dinosaurs Including Theropods

Other types of dinosaur also walked over the muddy surface, preserving their footprint impressions as trace fossils, picture E records the tracks of two, small theropod dinosaurs.

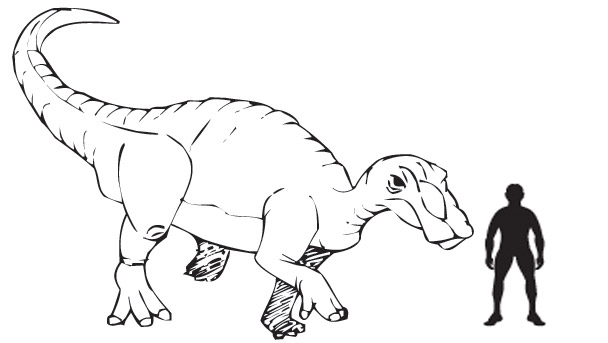

An Illustration of an Edmontosaurus (Hadrosaur)

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

As this part of Alaska is subject to occasional Earthquakes, steps have been taken to preserve as much data about the site as possible. Over the last few years, the tracks have been carefully measured, photographed and recorded. In addition, many casts of individual prints have been made and these are now safely in storage at the Dallas museum. Some of these casts are on display, permitting members of the public to gain in insight into the ongoing research on polar dinosaurs.

Trace fossils such as surface trails and shallow burrows from insects and other invertebrates found amongst the dinosaur footprints led the scientists to conclude that this site represents a single event, one that was produced in the warmer months of the year – the polar summer.

Seasonal Distribution

Seasonal distribution of modern, extant, equivalent invertebrates suggest that the tracksite was formed in the warmest months of the year during the Late Cretaceous. How warm was it? Palaeoenvironmental studies indicate that this part of the world had a much milder climate than it does today. Summer temperatures could have averaged 12-14 degrees Celsius, whilst the darkest winter months would have led to freezing temperatures with perhaps occasional highs of 4 -5 degrees Celsius.

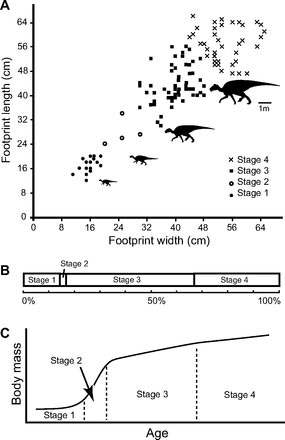

Duck-billed dinosaur footprints (the ichnogenus Hadrosauropodus, but believed to represent Edmontosaurus), in the 180 metre by 60 metre site were then measured (length v width measurements) and a scatter-plot graph generated. The scientists discovered that four different sized prints of duck-bills were present at the site. This suggests that adult animals roamed in herds that also contained sub-adults, juveniles and very young animals.

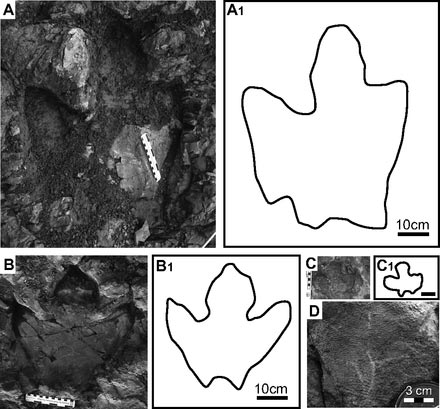

Scientists Identified Different Sized Duck-billed Dinosaur Prints

Picture credit: Perot Museum of Nature and Science

The picture shows photographs and corresponding scale drawings of three differently sized dinosaur prints found at the site. So well preserved were the prints from these hadrosaurs that something like fifty percent of the tracks preserved traces of the skin impressions from the underside of the dinosaur’s foot (D). These tracks suggest that this group of dinosaurs formed a herd structure similar to extant elephants. Elephants live in extended families with many different age groups represented in the herd.

Maastrichtian Faunal Stage

The fossilised footprints, estimated to be around 70 million years old, indicate that at least some types of plant-eating dinosaur may have lived in similar social groups.

In addition, the scientists looked at the frequency of the different sized prints across the site. The two largest classes of print made up 84% of all the footprints found. The smallest prints made up 13% but the second smallest footprints only represented 3% of all the tracks. The researchers have suggested that this frequency pattern reinforces the histological studies of dinosaur bones carried out by other palaeontologists that indicate duck-billed dinosaurs experienced a rapid growth spurt.

Scatter Graph of the Footprint Data Linked to Projected Hadrosaur Growth Chart

Picture credit: Perot Museum for Nature and Science

Different size classes are consistent with extant populations that breed seasonally (A), the bar graph (B) shows the relative frequencies of each growth stage with figure C plotting frequency against proposed hadrosaur growth stages. The tracks support earlier studies of duck-billed dinosaur bones that showed that these reptiles underwent a rapid growth spurt as relatively young animals. Presumably, this strategy had evolved as an adaptation against predation.

To read an article about hadrosaur growth rates: Duck-billed Dinosaurs Grew Fast to Avoid Tyrannosaurs.

The research team also suggest that since small hadrosaurs were members of the herd, then it was unlikely that these dinosaurs migrated northwards to take advantage of the long daylight hours before returning to the south to avoid the worst of the polar winter. The young hadrosaurs were probably not capable of making long migrations and this implies that these dinosaurs were year-round residents of the polar regions.

For models and figures of duck-billed dinosaurs and other Late Cretaceous prehistoric animals: CollectA Deluxe Prehistoric Life Figures.

Leave A Comment