Admiring the Remarkable Accipitridae (Eagles, Vultures etc.)

Eagles, Hawks and Vultures

It is not very often that we get the chance to get up close to extant “raptors” but an opportunity was taken recently by Everything Dinosaur team members to take some pictures of birds of prey at a Game Fair. Studying extant (creatures that live today), animals and birds can provide scientists with a better understanding of how extinct creatures might have behaved. Studying a bird such as a Vulture might provide some pointers to those researchers working on a group of pterosaurs known as the Azhdarchidae – the largest flying creatures known to science. Intriguingly, there were two birds that we took particular interest in. Firstly, there was a Old World Vulture within the collection, (we are not sure what the collective noun for a group of assorted birds of prey is), we think this was a young Ruppells Vulture (Gyps rueppellii), although our knowledge of ornithology is a little lacking. This large scavenger had the typical long neck devoid of feathers which for many years scientists had thought had evolved simply to permit the bird to stick its head deep into a carcase in order to feed without its feathers getting clogged with blood.

Admiring the Accipitridae

The Young Vulture – Gyps rueppellii?

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Necks Devoid of Feathers

Having a neck devoid of feathers seems to make sense when you stick it inside dead animals in order to feed, but recent research has suggested that a long neck with limited plumage may serve a second, equally important purpose. Thermo-regulation studies have shown that vultures lose a considerable amount of body heat through their heads and necks. One of the characteristics of azhdarchid pterosaurs such as Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx is that they had long, cylindrical neck bones. This gave them long, slender, but rather inflexible necks. Some scientists have proposed that since fossils of Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx are associated with sediment laid down in non-marine environments (granted H. thambena fossils are associated with an archipelago – Hateg), these pterosaurs were the Late Cretaceous equivalent of vultures. The long necks and large jaws would have enabled these prehistoric animals to reach deep inside the carcase of a dead dinosaur to feed.

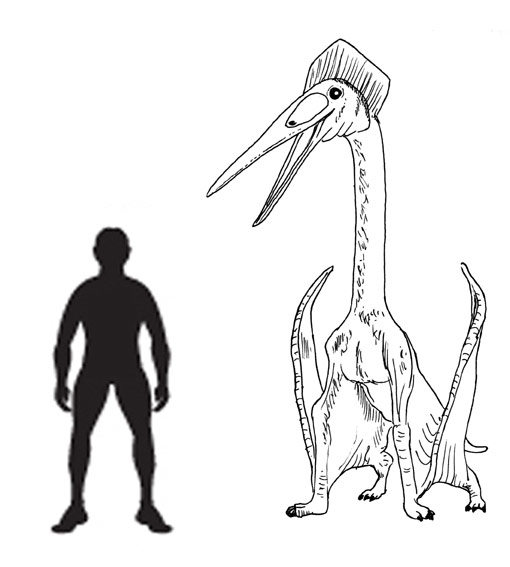

A Scale Drawing of the European Azhdarchid Pterosaur – Hatzegopteryx

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Other theories have proposed that these animals may have hunted like giant storks, stalking prey including small dinosaurs, on the ground and then grabbing the unfortunate victim with their long slender jaws before swallowing it whole. The debate as to what these animals ate, how they hunted and how they behaved goes on. What is known is that a number of large pterosaurs were covered in fine, insulating hair. Perhaps the long neck was particularly sparsely covered with insulating hairs and this part of the body served as a thermo-regulatory device just as it seems to do in modern-day vultures.

The second bird of prey we took a close look at was the American Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), simply because it looked magnificent. After all, any bird that features on the Presidential Seal of the U. S. President has got to be worth taking a second look at.

The American Bald Eagle

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

As for the name – Bald Eagle, we think the name originates from the old English word for white. It certainly is a magnificent creature.

For flying reptile figures and other prehistoric animal models: Models of Pterosaurs and Prehistoric Animals (CollectA Prehistoric Life).