Rare Ichthyosaur Snout Shows Signs of Prehistoric Battle

Tell-Tale Gouges in Fossil Jaws indicate Ichthyosaur Fight

This week it is the ichthyosaurs that have dominated the articles on our blog site. Firstly, there were lots of Jurassic ichthyosaur fossils to see at the Lyme Regis Fossil Festival, we commented on the fear of accidents as people wandered to closely to the dangerous cliffs as they searched for fossils. Then we had to locate a particular ichthyosaur model for one of Everything Dinosaur’s customers – we ended up going on a hunt for ichthyosaurs in our own warehouse. Now we have the published information on the evidence of a fight between an ichthyosaur and an unknown assailant. The attacker left tell-tale scratches and marks on the fossilised snout of its victim. This fossil provides evidence of behaviour, two fossils in one as it were. We have the body fossil (the bones) plus the bite marks, evidence of activity and therefore a trace fossil.

Ichthyosaur

First a quick reminder, the Ichthyosauria is an Order of extinct marine reptiles that evolved in the early Triassic and became extinct approximately 80 million years ago, towards the end of the Cretaceous Period. With their streamlined bodies, many members of the Ichthyosauria looked like dolphins, although the resemblance was only superficial, they are not closely related; although scientists have speculated that many marine reptiles, including the ichthyosaurs were warm-blooded just like dolphins.

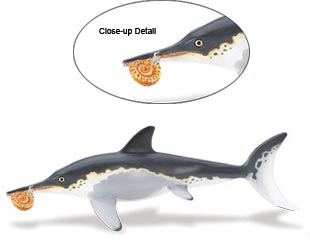

A Model of an Ichthyosaurus (Carnegie Safari Ichthyosaurus)

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The picture above is of an Ichthyosaurus model, the Carnegie Collectibles Ichthyosaurus model.

To view the range of prehistoric animal models and figures in the Wild Safari Prehistoric World range: Safari Ltd. Wild Safari Prehistoric World.

The fossilised snout of this particular ichthyosaur was discovered in South Australia, near the town of Marree. The fossil has been dated to approximately 120 million years ago (Aptian faunal stage), the Early Cretaceous a time when much of the landmass we now know as Australia was at the bottom of a vast sea that teemed with prehistoric life despite being close to the South Pole.

The gouged and scratched jaw indicate that this animal was involved in a fight with another sea monster, but scientists writing in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica remain uncertain as to who the attacker was. The fossil snout suggest that this individual ascribed to the ichthyosaur genus of Platypterygius may have been more than five metres in length – a sizeable beast but the snout shows that in the Cretaceous seas, being big did not keep you out of trouble. The series of scratches and gouges with some more than a centimetre long are testament to this.

This individual, spanning about 16 feet in length, is a member of the genus Platypterygius.

Researcher Benjamin Kear of Uppsala University (Sweden) commented:

“The bone itself was not broken, rather it was scored, suggesting that the bite was strong but not ‘bone puncturing’ like that of a predator.”

The research team suggest that this Platypterygius survived its encounter, as the wounds show signs of healing and a there is evidence on the bone of a callus forming – part of the healing process.

Although, the Cretaceous Period was generally much warmer than today, the sea temperatures at such a latitude would have been much colder than the habitats normally associated with marine reptiles – such as the Jurassic aged ichthyosaur fossils found in Dorset. These animals swam in a warm, shallow sea, a similar environment to the Caribbean sea of today. Whereas, the marine reptiles living around the coast of what was to become Australia, had to cope with extremely cold winters, prolonged periods of darkness for much of the year a sea so cold that icebergs would have been common – hence the belief of many palaeontologists that many types of marine reptile were actually warm-blooded.

The large red arrow in the picture is highlighting the indentation in the bone caused by the tooth of another animal. Scientists are confident that these teeth marks and scratches were not made as scavengers fed on the corpse of the dead ichthyosaur as the wounds show signs of healing indicating that the animal was very much alive when it was attacked.

But which animal was responsible for the marks on the ichthyosaur’s snout. Palaeontologists have been turning detective to find clues as to the identity of the attacker as they investigate a case of grievous bodily harm (gbh) from 120 million years ago.

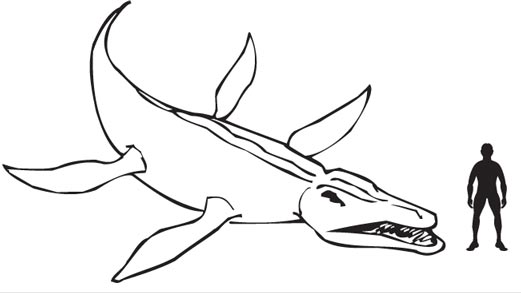

Sharing the seas with the ichthyosaurs were strong-jawed, giant pliosaurs such as Kronosaurus. Many of these pliosaurs were the apex predators in this environment, animals like Kronosaurus (K. queenslandicus) reached lengths in excess of ten metres, and their jaws were over two metres long.

An Illustration of Kronosaurus – A Suspect in the Ichthyosaur Assault?

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

To read more about this fierce pliosaur: The Fearsome Kronosaurus.

Benjamin Kear stated that this prehistoric animal was a huge predator “with a head the size of a small car and teeth as big as bananas”, however, the marks on the ichthyosaur jawbone don’t indicate an attack from a pliosaur, even a small one. An accidental encounter with a long-necked, fish-eating plesiosaur could have resulted in the damage seen. Perhaps, these animals corralled fish into bait balls, just like some marine predators do today and in the resulting feeding frenzy the ichthyosaur got bitten by a plesiosaur, whose teeth would have been conical in shape and would have left wounds similar to those seen on the fossil. This would be an example of interspecific competition, when two different species, in the case the ichthyosaur and a plesiosaur come into conflict.

The research team have also suggested that the damage seen on the jawbone was as a result of intraspecific competition – a fight between two animals of the same species, possibly over mates, food or territory.

Whatever the cause of the injuries, this fossil provides scientists with evidence of behaviour, making this fossil particularly significant.