Research shows that Dinosaurs May have Grown Quickly but Died Young

The Life of a Dinosaur – Short and likely to end Unpleasantly

Although many scientists now believe that dinosaurs are closely related to birds there has been considerable debate about the length of dinosaurs lives, how quickly they grew and when they reached an age when they could reproduce.

Newly Published Research

Dinosaurs Grew Quickly

The finding, Werning said, suggests that dinosaurs were born precocious and suffered high adult mortality, making early reproductive maturity necessary for survival. It seems that all those monster movies were right when the dinosaurs in the picture end up deceased, with the chances of few dinosaurs living into old age, having the ability to raise a family early makes evolutionary sense.

“This is an exciting finding, because age at reproductive maturity is related to so many things,” said the students’ adviser, Kevin Padian, who is a professor of integrative biology and a curator in UC Berkeley’s Museum of Palaeontology. “It also shows that you can’t use reptiles as a model for dinosaur growth, as many scientists still do.”

Diverse Dinosauria

Unfortunately, dinosaurs are an exceptionally diverse group with huge titans such as Argentinosaurus and Brachiosaurus as well as very much smaller members of the group like Microraptor. Such very different animals may well have exhibited contrasting growth rates and life spans. It could be imagined that a small theropod such as Microraptor may have led a short life, with a rapid growth rate to maturity, perhaps similar to the life styles and growth rates in garden birds. Garden birds such as blackbirds and robins can grow from a hatchling into a fully fledged adult in under a year.

Animals such as the sauropods may have lived for much longer and continued growing throughout their lives, although their growth rates would have decreased once they had reached full maturity. It has been estimated that a sauropod such as Brachiosaurus could have lived for as much as 150 years.

Pinpointing the age of reproductive maturity “opens up so many complementary avenues of dinosaur research,” Werning commented. “You can talk about dinosaur physiology, lifespan and reproductive strategies”.

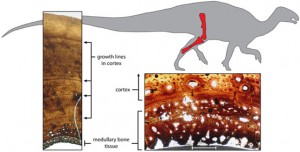

The conclusion, reported the week of Jan. 14 in the on line early edition of the journal “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences”, comes from an analysis of the only three dinosaur fossils that have been definitively identified as female. Thin slices of these dinosaurs’ fossil bones all show an internal structure similar to tissue found in living female birds – a layer of calcium-rich bone tissue called medullary bone that is deposited in the marrow cavity just before egg-laying as a resource for making eggshells.

Studying Dinosaur Bones and Eggshells

Dinosaurs, which also laid eggs, apparently stored calcium in similar structures prior to ovulation. In their new paper, Werning and Lee report that leg bones from the carnivorous Allosaurus and the plant-eater Tenontosaurus both contained this structure, which means both creatures died shortly before laying eggs. The researchers concluded that these dinosaurs were both mere adolescents, because the Allosaurus was age 10 and the Tenontosaurus age eight at time of death, and prior studies have shown that these types of dinosaurs probably lived up to 30 years.

Werning and Lee also confirmed that a third bone, from a female Tyrannosaurus rex reported by Museum of the Rockies palaeontologist Mary H. Schweitzer in 2005, contained medullary tissue upon the dinosaur’s death at the age of 18. Werning noted that all three dinosaurs might have reached reproductive maturity much earlier.

“We were lucky to find these female fossils,” Werning said. “Medullary bone is only around for three to four weeks in females who are reproductively mature, so you’d have to cut up a lot of dinosaur bones to have a good chance of finding this.”

In the past 10 to 15 years, studies of dinosaur bones have revealed much about the growth strategy of dinosaurs because bone lays down rings much like tree rings. If, as with trees, each ring signifies one year, then dinosaurs grew rapidly after birth and continued to grow over several years until death. Despite the presumed close relationship between dinosaurs and reptiles, dinosaurs grew faster than living reptiles, and their bones had a bigger blood supply.

Among living vertebrates, only birds and mammals exhibit such fast growth, perhaps this is another indication that dinosaurs were indeed warm-blooded like birds and mammals. Birds and small mammals grow quickly to maturity and then become reproductively mature, but large mammals reach maturity just before growth slows.

Attempts to determine when dinosaurs became able to reproduce, and thus whether they more closely resemble birds or mammals, have been difficult because there have been no clear signs of reproductive maturity in dinosaur skeletons.

Medullary Bone

Hence the excitement when Schweitzer discovered medullary bone in a T. rex femur. Though other palaeontologists have searched fruitlessly for similar signs in fossil bones, Werning and Lee found success by focusing on Tenontosaurus (a large hypsilophodontid) and Allosaurus, a predator from the Late Jurassic whose fossils are relatively common (well at least for a carnivorous dinosaur anyway).

Werning was able to obtain many fossil bone slices from the Oklahoma Museum of Natural History. Both a femur (thigh bone) and a tibia (shin bone) from the same fossilised Tenontosaurus showed medullary bone, while growth rings in its bones indicated the pregnant dinosaur was eight years old.

“These were prey dinosaurs, so they were probably taken out when really young and small or when old,” Werning said. “So, if you don’t reproduce early, you lose your chance.”

Lee, on the other hand, focused on Allosaurus fossils from the Cleveland-Lloyd quarry in Utah, where several thousand Allosaurus bones from at least 70 individuals have been discovered. A smaller and older version of T. rex, Allosaurus lived 155 to 145 million years ago in the Late Jurassic. Lee found one tibia with medullary bone from the University of Utah vertebrate palaeontology collection.

The two researchers are continuing to analyse thin slices of fossilised dinosaur bone in hopes of finding more skeletons with medullary bone.

The work was made possible by grants from the Geological Society of America, the Palaeontological Society and the University of Oklahoma Graduate Student Senate to Werning and by grants to Lee from the Jurassic Foundation and UC Berkeley’s Department of Integrative Biology.

This article has been reproduced from press release extracts from the University of California.

Dinosaur Growth Rates Demonstrated by Tenontosaurus

CAPTION: Cross-sections through the fossilised tibia or shinbone of a 120-million-year-old female Tenontosaurus skeleton, showing growth rings and medullary bone laid down in the marrow cavity just prior to egg laying. This individual died at the age of eight, shortly before she would have laid her eggs.

Picture credit: Sarah Werning/UC Berkeley & Andrew Lee/Ohio University; fossil courtesy of the Oklahoma Museum of Natural History