Scientists have re-examined fossil bones associated with the Chinese mamenchisaurid dinosaur Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum and propose that the robust limb bone associated with this sauropod represents an entirely different genus which they have named Rhomaleopakhus turpanensis.

The forelimb bones are exceptionally stout and strong, particularly the ulna. These fossils represent a giant sauropod. The researchers, who include Professor Paul Barrett of the London Natural History Museum, speculate that strong forelimbs could have helped this dinosaur to “push off” from the ground so that it could rear up onto its back legs to feed. Strong forelimbs would also have helped to resist the deceleration forces as the huge dinosaur lowered itself back onto all fours.

The robust right forelimb of Rhomaleopakhus turpanensis (specimen number IVPP V11121-1) showing the bones in approximate anatomical position (anterior view). The bones had been ascribed to Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum although they were not found at the same location as vertebrate that led to the erection of the Hudiesaurus genus. The forelimb bones demonstrate several autapomorphies that led the research team to propose a new genus R. turpanensis. Picture credit: Upchurch et al.

Picture credit: Upchurch et al.

Note – the scale bar in the picture (above) equals 20 cm. Although, only described from bones from the right forelimb, it is estimated that Rhomaleopakhus (pronounced Row-ma-lee-oh-pack-hus) could have been between 25 and 30 metres long.

Core Mamenchisaurus-like Taxa

In 1993, a joint Chinese/Japanese field team uncovered sauropod fossil material from the Jurassic-aged Kalazha Formation within Shanshan County in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region of north-western China. The fossils consisted of a single, huge vertebra, four teeth and a nearly complete right forelimb. On the basis of these fossils, a new member of the Mamenchisauridae family of long-necked dinosaurs was erected in 1997 – Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum. This dinosaur’s name translates as Chinese/Japanese butterfly lizard, in recognition of the co-operation between China and Japan in field excavations and because the vertebra had a flat butterfly-shaped process on the front base of the vertebral spine.

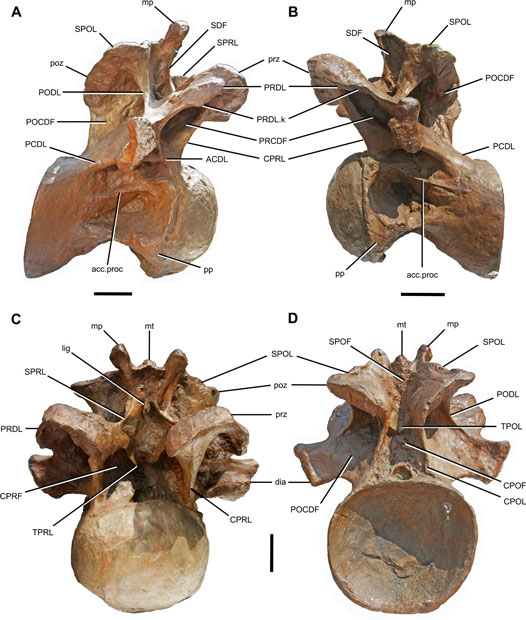

Posterior cervical vertebra of Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum (IVPP V11120; holotype). A, right lateral view; B, left lateral view; C, anterior view; D, posterior view. Scale bar = 10 cm. Picture credit: Upchurch et al

Picture credit: Upchurch et al

Having reassessed the fossil material ascribed to Hudiesaurus the scientists, writing in the “Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology”, suggest that the bone from the spine, with its unique anatomical characteristics should remain the holotype material for H. sinojapanorum, but the forelimb which was found 1.1 kilometres from the vertebra and the teeth should not be assigned to Hudiesaurus. Indeed, the researchers propose that the robust forelimb with its own unique anatomical characteristics represents a new taxon. The teeth are too poorly preserved and can only be assigned to “core Mamenchisaurus-like taxa”.

Closely Related Mamenchisaurids

The researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, University College London as well as the London Natural History Museum undertook a phylogenetic assessment of the Hudiesaurus and the newly assigned Rhomaleopakhus fossil material. The analysis indicates that Hudiesaurus is closely related to the “core Mamenchisaurus-like taxon” Xinjiangtitan, although differences between them indicate that they should remain separate genera for the time being. The four, poorly preserved teeth cannot be identified with any certainty, but they too probably represent a mamenchisaurid. Rhomaleopakhus too is very likely a member of the Mamenchisauridae family, albeit closely related to Chuanjiesaurus and Analong from the Middle Jurassic and found in Yunnan Province (south-western China).

A view of the giant PNSO Er-ma the Mamenchisaurus dinosaur model. A typical mamenchisaurid sauropod, with a very long neck. Mamenchisaurids have many more cervical vertebrae (18+) when compared to most other sauropods. The evolution of an exceptionally long neck could have occurred as a way to exploit other food resources or perhaps through sexual selection.

View the extensive PNSO prehistoric animal model range: PNSO Dinosaur Figures.

The scientific paper: “Re-assessment of the Late Jurassic eusauropod dinosaur Hudiesaurus sinojapanorum Dong, 1997, from the Turpan Basin, China, and the evolution of hyper-robust antebrachia in sauropods” by Paul Upchurch, Philip D. Mannion, Xing Xu and Paul M. Barrett published in the Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Dinosaur Toys.

Leave A Comment