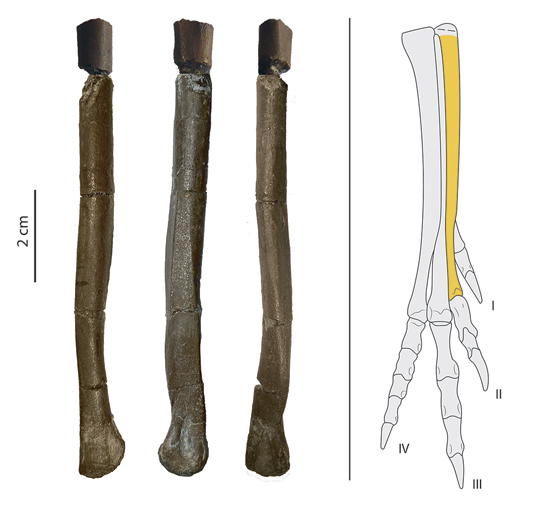

A team of international scientists including Steve Brusatte (University of Edinburgh), have confirmed the presence of troodontids in the Late Cretaceous of Europe. A new species of troodontid has been erected based on the discovery of a single metatarsal bone (the second metatarsal bone from the right foot), from Late Cretaceous strata in the Talarn Formation exposed at the Sant Romà d’Abella site in the southern Pyrenean region of Spain. This new dinosaur has been named Tamarro insperatus.

Picture credit: Oscar Sanisidro

Found in 2003

The single fossil bone indicating the presence of troodontids in Europe was found in September 2003 by a team of palaeontologists from the Museu de la Conca Dellà (Lleida, Isona, Spain) at the Sant Romà d’Abella site (Spain). It was found in fluvial floodplain deposits believed to have been laid down just 200,000 years or so before the K-Pg mass extinction event.

The fossil bone was found in the same horizon as plant fossils and the type specimen of the lambeosaurine Pararhabdodon isonensis, the metatarsal was found in close proximity to the Pararhabdodon type specimen, these are the only two vertebrates known from this site.

The Dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Europe

During the Late Cretaceous, high sea levels ensured that much of the European landmass we know today was underwater. Numerous islands existed, creating an extensive archipelago and several dinosaurs associated with these islands exhibit dwarfism or other unusual features associated with isolated ecosystems. Very little is known about the Theropoda that inhabited these islands. For example, the presence of troodontids in Europe has been debated for a long time. Several troodontid-like and Paronychodon teeth (a nomen dubium taxa referred by some to the Troodontidae), were recovered from the Campanian and Maastrichtian deposits of the ancient Hateg (Romania) and Ibero-Armorican (Portugal, France and Spain) islands, but this fossil bone provides definitive, unequivocal proof of these theropods being present in the Late Cretaceous of Europe.

Picture credit: Albert G. Sellés (Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafon/Museu de la Conca Dellà)

A Basal Troodontid with Asian Origins

An analysis of the bone and a phylogenetic assessment suggests that Tamarro is a basal member of the Troodontidae family and most likely a representative of the Asian subfamily the Jinfengopteryginae. The research team speculate on how a dinosaur with relatives in Asia could have become established in Europe. Maastrichtian troodontids like Tamarro could have reached Europe during the Cenomanian faunal stage and persisted on these islands until the K-Pg extinction event.

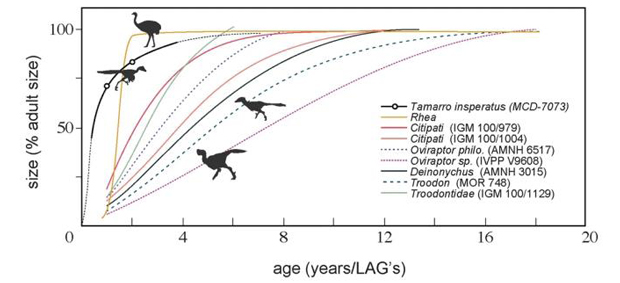

Estimated at around two metres in length Tamarro is around twice the size of other related troodontids. A close examination of the bone (cross-sectional histology), reveals that the metatarsal came from a subadult animal that was growing rapidly. Although troodontids are known to have fast growth rates, Tamarro seemed to be growing much quicker than other members of the Troodontidae, perhaps reaching full maturity in around two years.

The genus name is derived from the Catalan word “Tamarro” which refers to a small, mythical creature from local folklore. The species or trivial name “insperatus” is from the Latin for unexpected, a reference to the unexpected discovery of the fossil bone.

The scientific paper: “A fast-growing basal troodontid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the latest Cretaceous of Europe” by Albert G. Sellés, Bernat Vila, Stephen L. Brusatte, Philip J. Currie and Àngel Galobart published in Scientific Reports.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Dinosaur Models and Gifts.

Leave A Comment