Twisting and Turning Tyrannosaurs Made them Top Predators

New Study Suggests Tyrannosaurids More Manoeuvrable than Other Large Theropods

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and the Oklahoma State University Centre for Health Sciences have applied mathematical models to assess the manoeuvrability of predatory dinosaurs. This research, published in the on-line journal PeerJ, involving numerous collaborators, suggests that large bodied tyrannosaurs were more agile and able to turn more sharply than other similar sized theropods such as allosaurs and carcharodontosaurids.

A Large Tyrannosaur Attacks a Styracosaurus

Picture credit: John Gurche

A Factor in the Evolutionary Success of Tyrannosaurs

The research involving complex mathematics, a study of animal anatomy and physics compared how rapidly meat-eating dinosaurs could turn their bodies. In summary, the scientists concluded that tyrannosaurs could attack smaller, faster and more dangerous prey. It is suggested that the greater manoeuvrability of these carnivores may have been a factor in their evolutionary success.

Associate Professor at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, Eric Snively, in collaboration with co-author Haley O’Brien (Oklahoma State University Centre for Health Sciences) along with several other leading palaeontologists such as Professor Phil Currie (University of Alberta), demonstrated that whether a tyrannosaur was dog-sized or a fully-grown, mature adult, it retained its agility and manoeuvrability.

Three-dimensional Computer Models Used to Test Tyrannosaurid Manoeuvrability

Picture credit: University of Wisconsin-La Crosse

Enhanced Agility Compared to Other Super-sized Theropods

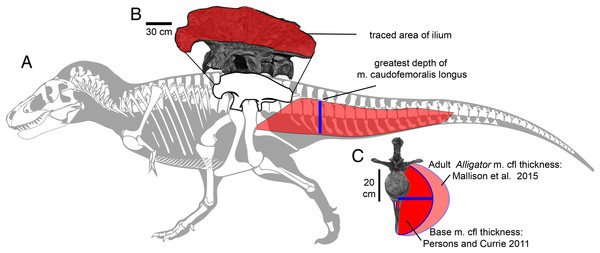

Tyrannosaurs were assessed to be more agile as they had relatively short bodies (anteroposteriorly short thoracic regions, and cervical vertebrae that aligned into posterodorsally retracted necks). In summary, shorter bodies meant less turning resistance and even their tiny arms helped! In addition, long, tall ilia bones (part of the hip), provided plenty of room for huge leg muscle attachments that gave the power needed for rapid turns and pivots.

The Size of the Ilia (Hip Bones) was Used to Infer Muscle Size Along with Postulated Tail Depth

Picture credit: PeerJ

In terms of the fastest results from the Tyrannosaur family, a horse-sized juvenile T. rex turned the quickest for its size, followed by the giant T. rex “Sue”, the enormous, mature adult from the Field Museum (Chicago).

Eric Snively described the T. rex turn as something akin to a “slow-motion-ten-tonne figure skater from hell,” quite apt in a way as T. rex fossils are known from the Hell Creek Formation.

Biomechanical Model Has Implications for Large Theropod Hunting Strategies

The researchers used very accurate anatomical assessments and rigorous statistics to create three-dimensional models that could then be tested for their range of movements. Different theropods were examined including Dilophosaurus, Ceratosaurus, Giganotosaurus, Sinraptor as well as numerous tyrannosaurs at different growth stages as well as smaller members of the Tyrannosauroidea Superfamily such as Raptorex. With respect to other theropods, tyrannosaurids were found to be increasingly agile without compromising their large body mass, such that in a pairwise comparison, tyrannosaurids were achieving the same agility performance as much smaller theropods. For example, a 500 kg Gorgosaurus had slightly greater agility scores than the 200 kg Eustreptospondylus, and an adult Tarbosaurus nearly twice the agility scores of the lighter Sinraptor.

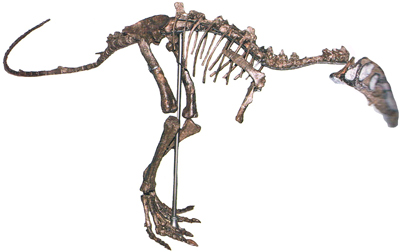

The Oxford University Specimen of Eustreptospondylus Used in the Study

Picture credit: Siri Scientific Press

Pursuing and Subduing Prey (Tyrannosaurs)

Enhanced agility and tight manoeuvrability in tyrannosaurids suggest that T. rex et al had superior abilities when it came to pursuing and subduing prey. This new research may have important implications when it comes to examining how large theropods hunted.

If tyrannosaurids were more agile and able to manoeuvre faster than other large predators they may have been more adept than earlier, super-sized, apex predators when it came to catching agile prey. It is postulated that this capability of tyrannosaurids is consistent with coprolite evidence that indicates that tyrannosaurids fed on juvenile ornithischians. Furthermore, it is proposed that healed tyrannosaur bite marks on fossilised remains of adult horned dinosaurs and hadrosaurs indicate an ability to outmanoeuvre quadrupedal prey.

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur commented:

“Whilst this is a fascinating piece of research, it is important that we don’t entirely discount observations of modern-day predator/prey interactions. Often an apex predator will select a weakened, or sick animal within a herd to attack. In addition, young animals are particularly vulnerable as they are smaller and less experienced in avoiding predators compared to adult animals.”

The largest non-tyrannosaurids, including Giganotosaurus, often lived in habitats alongside sauropod dinosaurs. These associations may suggest that allosauroids may have preferred less agile prey than did tyrannosaurids. It is also possible that stability conferred by high rotational inertia, as when holding onto giant prey, was more important for allosauroids than turning quickly.

The researchers intend to undertake research to assess the manoeuvrability of ceratopsids and other prey such as duck-billed dinosaurs before applying the same techniques to examine tyrannosaur bite forces.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.