Largest Pterosaur Mandible Ever Found

Giant Romanian Pterosaur Hints at Ecological Niches within the Azhdarchidae

Transylvania back in the Late Cretaceous was a very scary place. This central part of Romania, might be associated with vampires today, thanks mainly to Bram Stoker’s Gothic horror “Dracula”, but towards the end of the Mesozoic, much of Europe was under the sea, rising above the remnants of the once mighty Tethys was an island and real monsters including giant pterosaurs lurked there.

The island is known as Hateg Island and it was a very strange place indeed. There were dinosaurs, but the apex predator was an animal capable of flight, just like the blood-sucking protagonist from the 1897 novel. Huge azhdarchid pterosaurs stalked Hateg Island and an international team of researchers writing in the academic journal “Lethaia”, report finding the largest pterosaur jawbone known to science.

Huge Azhdarchid Pterosaurs Stalked Hateg Island

Picture credit: Mark Witton

Niche Partitioning Amongst Giant Flying Reptiles

Pterosaurs in the family Azhdarchidae, represent the largest flying animals to have ever existed, with the longest skulls of any terrestrial tetrapod. They were globally distributed, with azhdarchid fossils having been reported from every continent except Antarctica. However, despite their huge size (wingspans in excess of ten metres have been estimated for several species), their fossil record is extremely poor, with most species, even giants such as Quetzalcoatlus, known from a few fragmentary, mere scraps of bone.

The mandible fossil is part of the largest pterosaur mandible (lower jaw) found to date. The fossil was collected from Maastrichtian continental deposits near Vălioara in the Hațeg Basin, Romania. The azhdarchid pterosaur Hatzegopteryx thambema is known from these Upper Cretaceous sandstone deposits (Red Cliffs), but this new fossil cannot be confidently referred to H. thambema due to the absence of overlapping skeletal elements. In short, the lower jaw fossil of H. thambema which would correspond to the newly described mandible has not been found.

It has been suggested that this, as yet, unnamed Hateg pterosaur, may have been a relatively stocky, heavy-set flying reptile, with a short neck and a huge head. It is reported that comparisons with previously described large‐sized azhdarchid mandibles indicate a certain degree of morphological and probably ecological disparity within the Azhdarchidae. Different giants may have occupied slightly different niches in the ecosystem, in this way they could avoid direct competition. The dividing up of resources in this way is referred to as niche partitioning.

A View of the Red Cliffs in Romania (Location of Fossil Find)

Picture credit: Mátyás Vremir

A Six to Eight Metre Wingspan for a Pterosaur

Lead author of the study, published in “Lethaia” an international journal of palaeontology and stratigraphy, Mátyás Vremir of the Transylvanian Museum Society stated:

“It is not the largest pterosaur ever found, but it is the largest mandible recovered to date, with a reconstructed length of 110 to 130 centimetres. This might indicate a very large size pterosaur, possibly 8 to 9 metres in wingspan.”

A trio of enormous pterosaurs are associated with the Hateg Formation. With the discovery of this partial mandible, Transylvania can claim to be a “hot spot” for super-sized flying reptiles. It had been thought that towards the end or the Cretaceous, the Pterosauria were in decline, however, a paper published in March this year identified a Late Cretaceous ecosystem in Morocco with at least six coeval species of pterosaur including the presence of two azhdarchid pterosaurs, one of whom could have been a giant.

To read our article about the Moroccan fossil discovery: Pterosaurs More Diverse Than Previously Thought.

Fragmentary remains of another azhdarchid pterosaur from Romania, uncovered in 2009, which have yet to be formally described, confirm that Hateg Island was home to a variety of giant flying reptiles. The fossils associated with this pterosaur have been nicknamed “Dracula” by scientists.

A Piece of the Pterosaur Fossil Bones Nicknamed “Dracula” Eroding Out of a Cliff

Picture credit: Mátyás Vremir

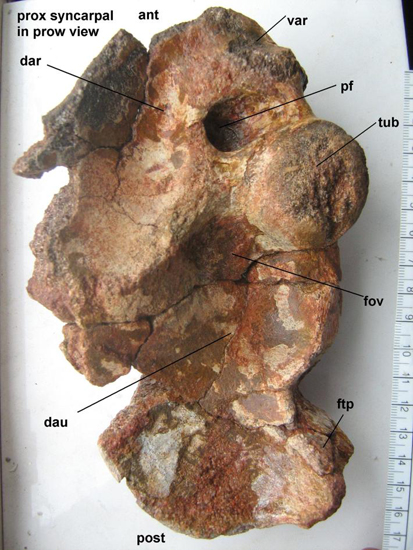

Specimen Number LPB (FGGUB) R.2347

The mandible fossil, part of the back of the lower jaw exhibits anatomical traits that are present in both azhdarchid and tapejarid pterosaurs. This suggests that the specimen (LPB (FGGUB) R.2347), comes from an animal that had a more basal position within the Azhdarchidae family. The researchers conclude that this bone shares a number of features with the smaller azhdarchoid Bakonydraco galaczi ,which is known from much older Cretaceous deposits in Hungary.

Vremir added:

“Except for a few scraps, after more than a century of fossil collecting in Transylvania, nothing was known about Pterosaurs until the last 16 years. In the past 10 years, the picture changed substantially and over 50 fossil specimens were collected from various sites.”

Azhdarchid Pterosaur Wrist Bone

Picture credit: Mátyás Vremir

The huge, partial mandible, the only part of the new animal found so far, was originally dug up in the Hateg region of Transylvania in 1978, but at the time it wasn’t recognised as a pterosaur fossil. Vremir and co-author of the scientific paper, Gareth Dyke, (University of Debrecen, Hungary), were visiting Bucharest’s fossil collection in 2011 and made the connection.

Flightless Giants

Using analogies such as the Elephant Bird of Madagascar and the Dodo from Mauritius, island life can lead to volant creatures evolving in very different directions. The Dodo and the Elephant bird were descended from birds that could fly, but once established on an island, with few predators, these birds adopted a ground-dwelling existence and over many subsequent generations they lost the ability to take to the air.

Mátyás Vremir and his colleagues speculate that some of the very largest Hateg pterosaurs may have taken a similar evolutionary route. Perhaps as young animals they could fly, a very good way to avoid terrestrial predators, but as they grew and became adults reaching a size whereby they were unlikely to be attacked by other animals, they were unable to fly.

Everything Dinosaur team members are aware that are number of papers are currently being prepared that explore this intriguing idea further.

The scientific paper: “Partial Mandible of a Giant Pterosaur from the Uppermost Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of the Hațeg Basin, Romania” by Mátyás Vremir, Gareth Dyke, Zoltán Csiki‐Sava, Dan Grigorescu and Eric Buffetaut.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.