Getting to Grips with Six New Species of Pterosaurs

The Pterosauria, that Order of winged reptiles that thrived alongside the dinosaurs were thought to have had their heyday in the Early Cretaceous. Only a single family, the Azhdarchidae (several of whom were giants), was known from the very end of the Cretaceous (Maastrichtian faunal stage). Many palaeontologists had thought that these flying reptiles, the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight, had gone into gradual decline, slowly but surely displaced by those rapidly evolving new masters of the air, the birds.

The Diversity of the Pterosaurs in the Late Cretaceous

However, a scientific paper, published this week in the academic journal “PLOS Biology”, challenges this view. A total of six new species, representing three families of pterosaurs have been discovered in Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) rocks in Morocco. This new discovery, the most diverse Late Cretaceous pterosaur fossil assemblage found to date, suggests that the Pterosauria may not have gradually faded away, as previously thought. Their long lineage probably ended abruptly, in essence, the Pterosauria met the same fate at the end of the Cretaceous as their archosaur cousins the Dinosauria.

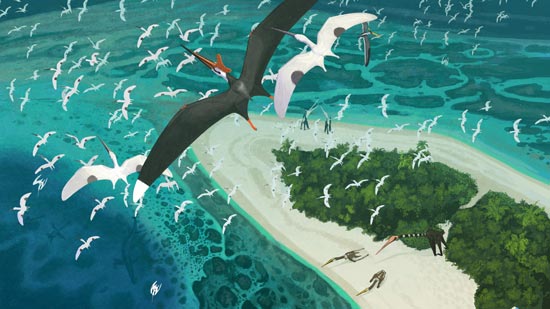

A Diverse Assemblage of Pterosaurs – Late Cretaceous Morocco

Picture credit: John Conway

A Treasure Trove of Ancient Vertebrate Fossils

Writing in the journal PLOS Biology, the researchers from the University of Bath, Portsmouth University and the University of Texas at Austin, identified a total of seven species of flying reptile from fragmentary and largely isolated fossils found in marine rocks from phosphate mines in northern Morocco (Ouled Abdoun Basin). Working in conjunction with local fossil hunters, the scientists were able to build up a collection of around two hundred pterosaur bones.

Over the years, commercial mining has revealed large numbers of marine vertebrates dating from the end of the Cretaceous and into the Palaeogene. Cretaceous fauna associated with these deposits include turtles, plesiosaurs, mosasaurs, sharks and lots of different types of teleost (bony fish). Occasionally the remains of terrestrial animals are preserved in such deposits, including the bones of Late Cretaceous dinosaurs, representing some of the youngest dinosaur fossils found.

To read our 2017 article about the discovery of an abelisaurid dinosaur: The Last Dinosaur in Africa.

Some of the Last Pterosaurs

The pterosaurs identified by the researchers range in size with the smallest found having a wingspan equivalent to that of an extant Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), to giants with wingspans approaching ten metres, three times bigger than the wingspan of the largest volant birds alive today. The fossil material has been dated to just over 66 million years ago, making these pterosaurs amongst the very last of their kind on Earth.

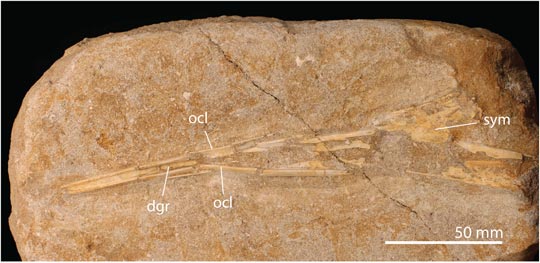

The Mandible of the Newly Described Nyctosaurid Alcione elainus

Picture credit: PLOS Biology

Key

dgr = dorsal groove, ocl = occlusal ridge, sym = symphysis.

Lead author of the study, Dr Nicholas Longrich, (Milner Centre for Evolution and the Department of Biology and Biochemistry, Bath University) stated:

“To be able to grow so large and still be able to fly, pterosaurs evolved incredibly lightweight skeletons, with the bones reduced to thin-walled, hollow tubes like the frame of a carbon-fibre racing bike. Unfortunately, that means these bones are fragile and so almost none survive as fossils.”

Six New Species of Pterosaur

The researchers were able to identify six new species of pterosaur, representing three different families:

- Tethydraco regalis (Pteranodontidae) – the youngest member of the Pteranodontidae family described to date. Estimated wingspan around 5 metres.

- Alcione elainus (Nyctosauridae) – wingspan estimated at about 2 metres.

- Simurghia robusta (Nyctosauridae) – a large pterosaur with a wingspan of around 4 metres.

- Barbaridactylus grandis (Nyctosauridae) – an even bigger pterosaur with a wingspan estimated to be about 5.2 metres.

- Quetzalcoatlus spp. (Azhdarchidae) – described from a single neck bone (cervical vertebra) which resembles the cervical vertebrae of Quetzalcoatlus (Q. northropi). Size estimates for this flying reptile are very speculative, however, it could have had a wingspan of around 4 metres based on comparisons with better known azhdarchid pterosaurs.

- Sidi Chennane specimen (Azhdarchidae) – not scientifically named as yet, known from a single, partial ulna (arm bone), measuring 362 mm long, but when complete it would have been around 600 to 700 mm in length. This suggests a giant azhdarchid pterosaur with a wingspan of approximately 9 metres. This specimen has been named after the phosphate mine where it was found, formal scientific description will depend on the discovery of more fossil material. The researchers conclude that this animal was probably related to the giant azhdarchid Arambourgiania philadelphiae, which is known from the Late Cretaceous of Jordan and the United States.

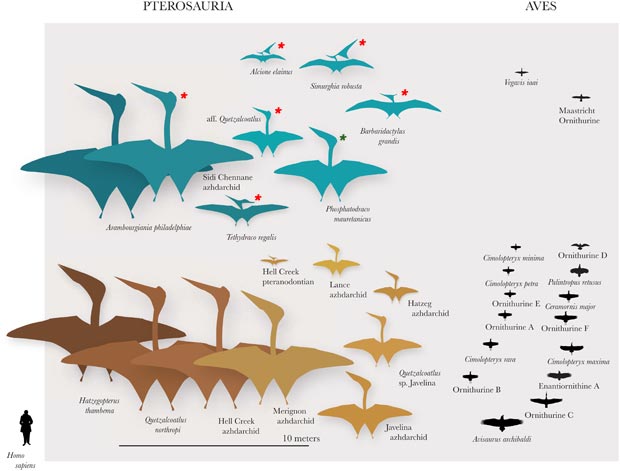

Late Cretaceous Pterosaur Faunas (Marine and Terrestrial) Compared to Late Cretaceous Birds

Picture credit: PLOS Biology with additional annotation by Everything Dinosaur

The diagram above compares the size disparity between Late Cretaceous pterosaurs with those of contemporaneous birds (coeval Aves – birds that lived at the same time as these flying reptiles). Pterosaurs shaded blue are associated with marine environments, pterosaurs shaded in brown are associated with terrestrial habitats. The six new species from the Ouled Abdoun Basin identified in the scientific paper have been given a red star. The one species from the Ouled Abdoun Basin that had been previously described (2003), has been labelled with a green star (the azhdarchid Phosphatodraco mauritanicus).

A Giant Pterosaur

The giant pterosaur referred to as the Sidi Chennane specimen is estimated to have approached Quetzalcoatlus in size, but it was much more lightly built and therefore, presumably weighed less. These proportions indicate a distinct flight mode and ecological niche, suggesting that giant pterosaurs occupied a range of niches in Late Cretaceous habitats. In addition, the researchers conclude that this flying reptile fossil assemblage demonstrates that the Maastrichtian pterosaurs show increased ecological niche occupation when compared to earlier Late Cretaceous pterosaurs (Santonian to Campanian faunas). This study also indicates that when it came to developing large body forms, the Pterosauria were able to outcompete coeval birds.

The Fossilised Partial Ulna of the Sidi Chennane Specimen

Picture credit: PLOS Biology

Key

ut = ulna tubercle, vp = ventral process

A 5% Increase in Known Pterosaur Species

Co-author of the study, Dr Brian Andres, from the Jackson School of Geosciences at The University of Texas at Austin, commented:

“The Moroccan fossils tell the last chapter of the pterosaurs’ story – and they tell us pterosaurs dominated the skies over the land and sea, as they had for the previous 150 million years.”

With around 130 pterosaur species described to date, these fossils from Morocco have led to a 5 percent increase in the known number of flying reptile species. This diversity of pterosaur species from Upper Maastrichtian deposits in Morocco suggest an abrupt mass extinction of the Pterosauria at the Cretaceous-Palaeogene boundary.

The scientific paper: “Late Maastrichtian Pterosaurs from North Africa and Mass Extinction of Pterosauria at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary” by Nicholas R. Longrich, David M. Martill and Brian Andres published in PLOS Biology.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the help of a press release from the University of Bath in the compilation of this article.

Visit the award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Amen this mad monkey all day