Rare Fossil Flakes and Dinosaur Dandruff

Dinosaur and Early Bird Dandruff

A team of international scientists led by researchers from University College Cork (Ireland), have discovered the fossilised remains of skin flakes from feathered dinosaurs and primitive birds that lived during the Early Cretaceous. The fossil flakes of skin, preserved amongst the plumage of the feathered creatures, has provided evidence on how dinosaurs shed their skin. Unlike many reptiles alive today, animals such as lizards and snakes, which shed their skin as a single piece or as several large pieces, it seems that basal birds and non-avian dinosaurs shed small epidermal flakes just like modern birds and mammals and that includes us with our dandruff.

Preserved Soft Tissue Evidence – Flakes of Skin in Maniraptoran Dinosaurs and the Basal Bird Confuciusornis

Picture credit: Nature Communications

Fossil Flakes

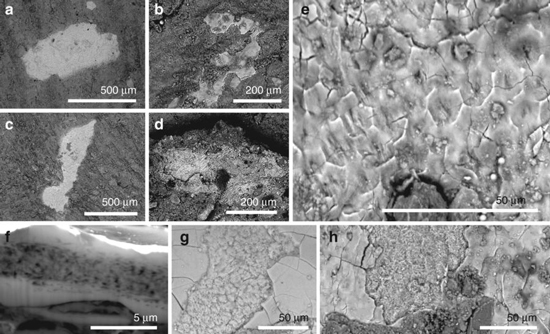

The photographs above (labelled a to h), show scanning electron microscope generated images of tissue in the Early Cretaceous Aves C. sanctus (a,e and f), the dromaeosaurid Sinornithosaurus (S. millenii) in photographs c and h, along with the therizinosaur Beipiaosaurus (B. inexpectus), photos b and g. The photograph labelled d, is a view of epidermal flakes preserved in association with the fossilised remains of Microraptor, which along with Sinornithosaurus is believed to have been capable of flight or at least gliding.

Studying the constituents of flakes of dinosaur skin, which come from animals that might have been volant, is very important. Palaeontologists can compare these flakes to living birds which are capable of powered flight. These flakes, in turn can be examined in relation to the flakes of terrestrial feathered dinosaurs such as Beipiaosaurus. Any differences in the composition of these flakes might provide scientists with further information on the aerial abilities of dinosaurs such as Microraptor and Sinornithosaurus.

An International Team

The scientists include researchers from the Chinese Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Bristol University, Linyi University (China), the Open University as well as Queen Mary University (London) and the University College Dublin (Ireland). They studied the fossil cells and dandruff from a range of Early Cretaceous Theropods and compared the skin flakes to those of living, extant birds.

Lead author of the research, Dr Maria McNamara (University College Cork), stated:

“The fossil cells are preserved with incredible detail, right down to the level of nanoscale keratin fibrils. What’s remarkable is that the fossil dandruff is almost identical to that in modern birds – even the spiral twisting of individual fibres is still visible.”

Getting to Grips with Corneocytes

The scientists used a scanning electron microscope (SEM), to examine the beautifully preserved, but microscopic fossilised fragments of skin associated with three feathered dinosaur specimens (Microraptor, Beipiaosaurus and Sinornithosaurus) and one Early Cretaceous bird Confuciusornis (Confuciusornis sanctus). All of these fossils are associated with the Jehol biota of north-eastern China.

A Pair of Fossilised Confuciusornis (Liaoning Province) Showing the Two Known Body Plans for these Ancient Birds

Just like our own flakes of skin, our dandruff, the fossil flakes consist of tough cells known as corneocytes. These cells are full of protein fibres (keratin), such was the quality of preservation that the SEM analysis was able to identify bundles of these fibres and even to hone in on single strands.

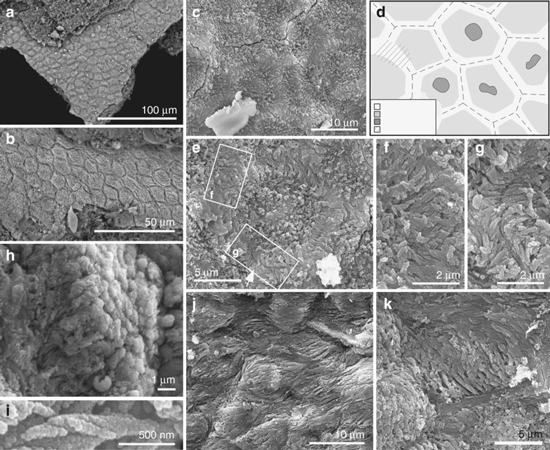

Scanning Electron Micrographs of Skin Flakes Associated with C. sanctus

Picture credit: Nature Communications

The photographs (above) show highly magnified images of the skin flakes associated with Confuciusornis. Closely packed polygons can be observed (a and b), whereas (c) shows a detailed view of the polygons and the first signs at this magnification of the bundles of fibrous keratin. The drawing (d) interprets the bundles as more darkly shaded areas in the central part of each polygon. Photograph (e) shows the area that was more closely observed (f and g) indicating the presence of fibres, whereas, (h) shows the fibrous bundle associated with a skin flake in an extreme close-up view.

Helical coiling of the tiny fibres is shown (picture i) and photographs j and k show polygons having been deformed by some form of stretching.

These structures were then compared to the flakes of skin associated with living birds, in this case, male specimens of Zebra Finches (Taeniopygia guttata) and the Java Sparrow (Lonchura oryzivora). In addition, the fossil evidence was compared to the moulted, downy feathers of a male American Pekin Duck (Anas platyrhynchos domestica).

Fossil Flakes Provide Clues About Dinosaur Metabolism

This research suggests that this ability to constantly shed skin evolved sometime in the late Middle Jurassic, around the same time as a host of other skin features evolved. The feathered epidermis of dinosaurs acquired many, but not all, anatomically modern attributes close to the base of the Maniraptora clade.

Dr McNamara explained:

“There was a burst of evolution of feathered dinosaurs and birds at this time, and it’s exciting to see evidence that the skin of early birds and dinosaurs was evolving rapidly in response to bearing feathers.”

Co-author, Professor Mike Benton (Bristol University), commented:

“It’s unusual to be able to study the skin of a dinosaur, and the fact this is dandruff proves the dinosaur was not shedding its whole skin like a modern lizard or snake but losing skin fragments from between its feathers.”

Corneocytes in Living Birds

Picture credit: Nature Communications

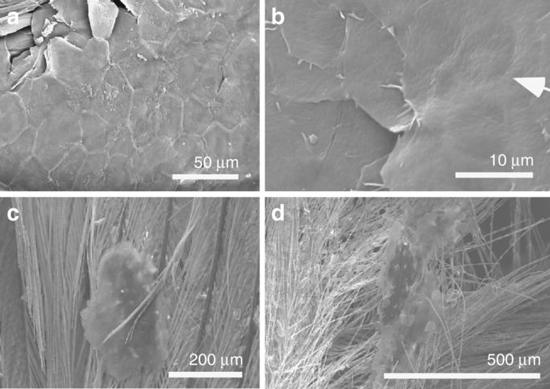

The four photographs above, show scanning electron micrographs of shed skin flakes in living birds. Note the polygonal structure (a), which is reminiscent of the shapes seen when the corneocytes of extinct dinosaurs and birds were studied. Photograph (b) shows a central depression in the cell associated with a pycnotic nucleus, whilst photographs (c and d) show skin flakes stuck to the bird’s feathers.

Modern birds have very fatty corneocytes with loosely packed keratin, which allows them to cool down quickly when they are flying for extended periods. The corneocytes in the fossil dinosaurs and birds, however, were packed with tightly bundled keratin, suggesting that the extinct creatures didn’t get as warm as modern birds, presumably because they couldn’t fly at all or for as long.

This suggests that Confuciusornis did not fly that well, if probably flew in short bursts, but may not have been capable of making prolonged flights. The lack of fatty corneocytes in those dinosaurs which are thought to have had some aerial ability (Microraptor and possibly Sinornithosaurus), sheds doubt on whether they were truly volant.

Could Some Dinosaurs Like Microraptor Fly?

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The picture (above) shows a Microraptor model from Safari Ltd.

To view this range of models and figures: Wild Safari Prehistoric World.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from the University College Cork (Ireland) in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Fossilised Skin Reveals Coevolution with Feathers and Metabolism in Feathered Dinosaurs and Early Birds” by Maria E. McNamara, Fucheng Zhang, Stuart L. Kearns, Patrick J. Orr, André Toulouse, Tara Foley, David W. E. Hone, Chris S. Rogers, Michael J. Benton, Diane Johnson, Xing Xu and Zhonghe Zhou published in Nature Communications.

Visit the website of Everything Dinosaur: Everything Dinosaur.