Dense Bones and Other Aquatic Adaptations in Spinosaurs

South American Giant Provides Further Information on Enigmatic Spinosaurs

A partial leg bone found in north-eastern Brazil has helped scientists to better understand the adaptations members of the Spinosauridae may have evolved to help them with their semi-aquatic lifestyles. Furthermore, the fragmentary fossil, a large partial tibia from the Aptian-Albian Romualdo Formation, (Araripe Basin, north-eastern Brazil), when compared to other spinosaur remains, indicates an individual dinosaur much larger than other South American spinosaurids. This single fossil suggests a sub-adult animal around ten metres in length, far larger than the other South American spinosaurids from the Araripe Basin such as Irritator and Angaturama.

Studying the Spinosauridae

A South American Lagoon Around 115-110 Million Years Ago – A Spinosaurid Attacks a Pterosaur

Picture credit: Julio Lacerda

For models and replicas of members of the Spinosauridae and other theropod dinosaurs: CollectA Deluxe Prehistoric Life Models.

Sail-back Dinosaur from the Heart of the Brazilian Outback

The Brazilian dinosaur fossil is providing another piece of the puzzle as palaeontologists strive to better understand the enigmatic spinosaurids. The discovery of the fossil bone and its implications for Spinosaur research has been published in the academic journal “Cretaceous Research”. The research was led by a team of Brazilian palaeontologists in collaboration with colleagues from Yale University, the University of Bonn and Trinity College (Dublin).

The partial tibia (lower leg bone) was found in Ceará, a state in the heart of the Brazilian outback. Although only a fragment of bone, its size in relation to other spinosaurid fossils suggests a dinosaur measuring about ten metres in length, considerably bigger than other South American members of the Spinosauridae.

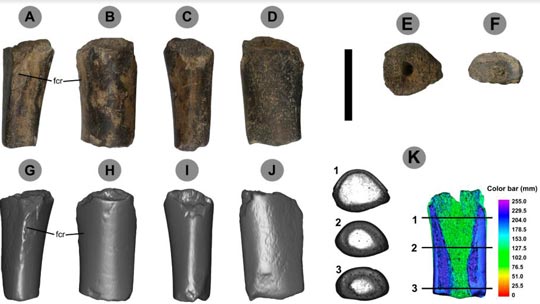

The Partial Tibia Bone (Various Views)

Picture credit: Cretaceous Research

Large Predators with an Aquatic Lifestyle

Over the last five years or so, there have been a number of papers published looking at how these large predators lived. Many palaeontologists believe that these theropods adopted a specialist lifestyle, becoming semi-aquatic and essentially piscivores. Interest in these enigmatic dinosaurs has certainly been piqued in recent years, especially with the publication of a fascinating paper in 2014 that proposed that Spinosaurus aegyptiacus was a semi-aquatic, obligate quadruped.

The partial tibia has anatomical traits previously only observed in the north African S. aegyptiacus, traits such as a reduced fibular crest and dense bones (osteosclerotic bones). These types of bones are characteristic of the limb bones of vertebrates that spend a lot of their time in water. The leg bones of hippos, for example, exhibit this condition. The partial tibia from north-eastern Brazil, supports the idea that spinosaurids were adapted to an aquatic environment, in addition, the Brazilian fossil is many millions of years older than those fossils associated with S. aegyptiacus, so, this suggests that high bone compactness was already present in Brazilian spinosaurids long before S. aegyptiacus evolved.

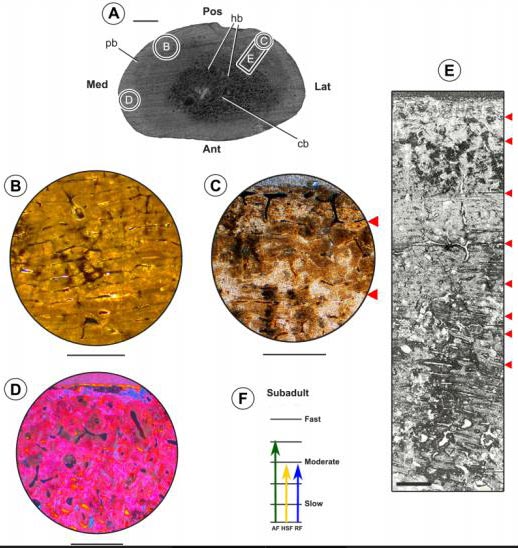

Cross-sectional Views of LPP-PV-0042 Indicating Bone Density and Growth Rate

Picture credit: Cretaceous Research

Fossilised bone cells in detail, observed under the microscope. Different growth pulses of the animal are represented by the red arrows. Absence of certain characteristics in the bone tissue lead palaeontologists to conclude the spinosaurid was a sub-adult and still growing when it died.

To read Everything Dinosaur’s article on the 2014 Spinosaurus paper: Spinosaurus – Four Legs are Better Than Two.

“Heavy Bones” of the Spinosauridae

The study was led by postgraduate student Tito Aureliano (Campinas State University, Unicamp, Brazil), along with researchers from the Federal University of Sao Carlos (Brazil). The dense bones of the Brazilian Spinosaur would have helped the animal to dive and to move in water in a similar way to a hippopotamus.

The dense bones are analogous to the lead weights used by divers to counteract their own buoyancy. This research suggests that osteosclerotic bones were present in the South American Spinosaurinae at least ten million years earlier than those associated with their north African cousins. It is not known when osteosclerotic bones evolved in spinosaurs, but this characteristic may have evolved relatively early in these types of dinosaurs.

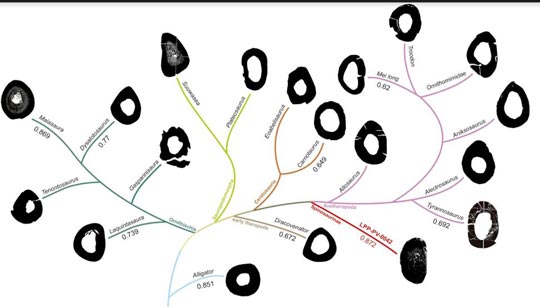

Bone Density Comparisons

Picture credit: Cretaceous Research

Commenting on the significance of this study, Tito Aureliano stated:

“It may be possible that Brazilian spinosaurs were the first to adopt this way of life. Now we need to investigate an even older species.”

An Example of Convergent Evolution

Several types of not-closely related vertebrates have dense bones, reflecting an adaptation to an aquatic lifestyle. Penguins, crocodiles and sealions along with hippos and spinosaurids have these types of bones, this is an example of convergent evolution.

Aline Ghilardi (Federal University of Sao Carlos) explained:

“It is interesting how this adaptation evolved multiple times in different groups of animals that adopted the same lifestyle.”

The spinosaurids evolved in a different direction when compared to most of the Theropoda. Whilst most dinosaurs evolved ways to make the skeleton lighter, epitomised in the extreme pneumaticity observed in birds, the spinosaurs developed a way to make their skeleton heavier. This aided them when it came to occupying a very distinct and specialised niche amongst the Dinosauria.

South American Giants

South America might be famous for its huge Cretaceous plant-eating dinosaurs such as the titanosaurids Argentinosaurus, Patagotitan and Dreadnoughtus but the partial tibia bone hints at super-sized predators too. An analysis of the fossilised cells showed that the studied dinosaur had not reached its maximum size by the time of its death and was still growing. This indicates that these dinosaurs could reach larger sizes than previously thought, the Araripe Basin Spinosaurinae could have been giants, which would make them the top predators of the Cretaceous coastal lagoons of Ceará.

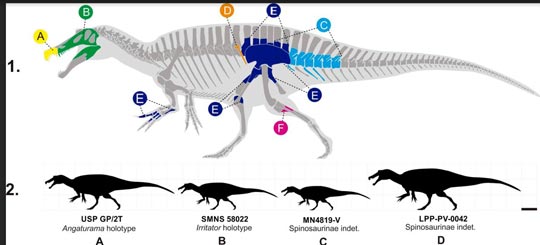

South American Spinosaur Size Comparison

Picture credit: Cretaceous Research

The image (above), shows all the known spinosaurid fossils from the Araripe Basin. The fossil used in this study is marked in pink (F). Note, figure 1 shows the fossil bones not to scale but figure 2 provides a scale comparison between the spinosaur specimens from the Araripe Basin. The largest spinosaurid found to date (LPP-PV-0042), was the subject of the research paper.

Pterosaur Vertebrae from Ceará

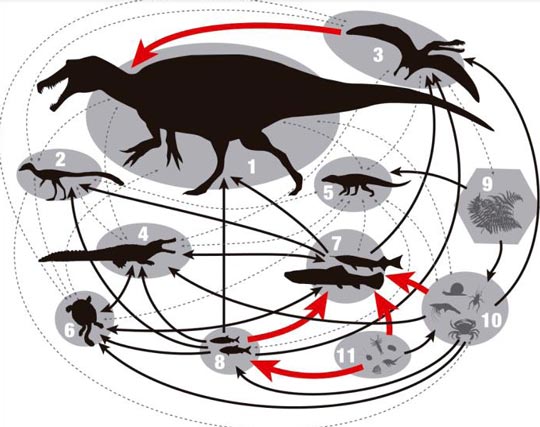

The Ceará state has been synonymous with amazing spinosaur fossil finds. In 2004, researchers led by the famous French palaeontologist Eric Buffetaut, described a remarkable fossil find from this region, three articulated pterosaur vertebrae (Ornithocheiridae) were found with the tooth of a spinosaurid embedded in one of the bones. This fossil represents direct evidence that spinosaurs included other prey items in their diets as well as fish. The broken tooth also provides evidence that the light bones of pterosaurs were much stronger than previously assumed.

A Food Chain of the Lagoonal Environment (Araripe Basin in the Early Cretaceous)

Picture credit: Cretaceous Research

Lots of questions about the Spinosauridae remain. For example, whether these aquatic adaptations are related to the establishment of a large system of lagoons between South America and Africa caused by the opening of the Atlantic Ocean during this period in Earth’s history. As with many whales today, was the adaptation of an aquatic lifestyle the trigger that enabled these theropods to evolve into giants?

Our thanks to Tito Aureliano ((Campinas State University, Unicamp, Brazil) for their help in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Semi-aquatic Adaptations in a Spinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil” by Tito Aureliano, Aline M. Ghilardi, Pedro V. Buck, Matteo Fabbri, Adun Samathi, Rafael Delcourt, Marcelo A. Fernandes and Martin Sander published in the journal Cretaceous Research.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.