Ellesmere Island Fossil Suggests Giant Birds Wandered Northern Canada

Fossils found in the 1970s on the remote Ellesmere Island, in the high Arctic suggest that giant, flightless birds roamed this part of the world during the Eocene. In a new study, published this week in the open access scientific journal “Scientific Reports” a single toe bone is described that indicates that Gastornis lived this far north around 52 to 53 million years ago.

Gastornis Roamed the Arctic During the Eocene

Model of a giant, flightless bird from Safari Ltd.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Colorado Boulder, describe a single toe bone, which suggests this two-metre-tall bird lived this far north. This fossil along with a partial humerus (upper arm bone) which as been identified as belonging to a member of the Presbyornithidae clade of waterfowl, also found in the same area, represent the oldest Cenozoic avian fossils found in the Arctic to date.

A Toe Bone Points to Gastornis

The toe bone is almost an identical match to Gastornis toe bones excavated from Wyoming from similar aged Eocene sediments. Scientists have speculated that Gastornis was likely to be an all year round resident of Ellesmere Island, although during the Eocene the Arctic was much warmer than it is today, this giant bird would still have had to endure harsh winters and almost four months of total darkness (the polar night).

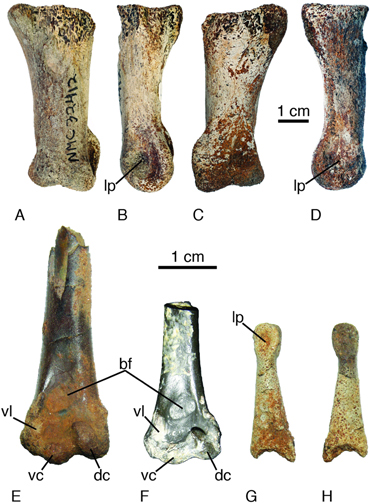

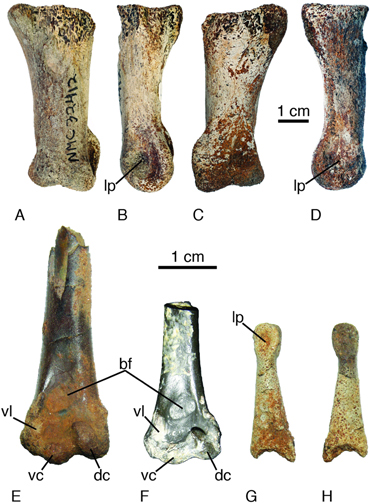

The Gastornis Toe Bone (Several Views) and Presbyornis Humeri

Gastornis toe bone (above).

Picture credit: Scientific Reports

The picture above shows the probable left phalanx (toe bone) of digit IV from a Gastornis (A) viewed from the top, (B) lateral, view, (C) view from underneath posterior/plantar view and (D) medial view. The other pictures show the a distal partial humerus (E) recovered from the Margaret Formation of Ellesmere Island (Canadian territory of Nunavut) compared to a Presbyornis specimen (F) from the University of California Museum of Palaeontology. The fossil bone (pictures G and H) represents an indeterminate pedal phalanx, probably from digit III on the left side. This specimen also comes from the Ellesmere Island locality.

Key

- bf = brachial fossa

- dc = dorsal condyle

- lp = collateral ligament pit

- vc = ventral condyle

- vl =facet for the ventral collateral ligament on the ventral supracondylar tubercle.

Specimen (E) the distal humerus assigned to the Presbyornithidae, is much larger than the Californian specimen. The extensive pitting of the bone is not regarded as sign that this is from a juvenile individual. Lack of further fossil evidence precludes any significant calculations as to the size of the Arctic Presbyornis in relation to its contemporaries from more southerly latitudes.

Gastornis

The fact that Gastornis (also referred to as Diatryma), fossil evidence has been found on Ellesmere Island has been discussed before, this flightless bird appears on a few faunal lists, but this is the first time that the bone has been closely examined and described in detail.

Very Rare Fossil Find

One of the researchers, co-author of the paper Jaelyn Eberle (Associate Professor in Geological Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder) stated:

“We knew there were a few bird fossils from up there, but we also knew they were extremely rare.”

Around 53 million years ago the environment of Ellesmere Island was very different from that of today. It was much warmer and wetter with a significant portion of the island forming a swamp dominated by Cypress trees. Living alongside Gastornis and Presbyornis were turtles, crocodilians, primates and large mammals such as tapirs.

Originally thought to be a fearsome carnivore, recent research indicates Gastornis probably was a vegan, using its huge beak to tear at foliage, nuts, seeds and hard fruit.

To read an article about our changing perceptions of Gastornis: Was the “Terror Bird” Gastornis a Herbivore?

The second Ellesmere Island prehistoric bird described in the paper is Presbyornis, a member of the duck family but with much longer legs. The research team compared fossils from Wyoming to the Ellesmere Island specimen and they could not find any significant differences, even though the fossils were 2,500 miles apart. This might indicate that these types of birds migrated up to the Arctic, perhaps to breed, in a similar fashion to a number of North American duck and goose species today. Alternatively, Presbyornis might have been a year round resident of Ellesmere Island.

A New Analysis of Eocene Avian Fauna

This new analysis of Eocene avian fauna from the high Arctic has implications for the rapidly warming Arctic climate of today.

Associate Professor Eberle explained:

“Permanent Arctic ice, which has been around for millennia, is on track to disappear. I’m not suggesting there will be a return of alligators and giant tortoises to Ellesmere Island any time soon. But what we know about past warm intervals in the Arctic can give us a much better idea about what to expect in terms of changing plant and animal populations there in the future.”

The CollectA range of scale figures contains a number of replicas of Eocene animals and a model of a flightless bird (Kelenken). To view this range: CollectA Deluxe Prehistoric Life.