Australopithecus sediba – Jaw Study Suggests a More Delicate Bite

Australopithecus sediba – Bio-mechanical Study Hints at Diet

South Africa might be regarded by many as the “cradle of humanity”, thanks to the wealth of Australopithecus and early hominin fossils found in that part of the world. Thanks to a collaborative research effort involving a bio-mechanical study of skull strength and bite forces, it seems that further light is being shed on the diet of one of southern Africa’s most famous early residents Australopithecus sediba. This new research may help palaeoanthropologists to further refine the evolutionary position A. sediba in relation to the hominins and ultimately this Australopith’s relationship to our own species.

H. sapiens Compared to A. sediba and Pan troglodytes (Chimpanzee)

A. sediba is in the middle, the human to the left of the picture with the chimp skeleton on the right.

Picture credit: University of Witwatersrand

Fossils Found in 2008

Fossils which came to be known as A. sediba were discovered in 2008 at the famous dig site of Malapa in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site, located around thirty miles north-west of the city of Johannesburg. Research published in 2012 suggested that this gracile, possible early human ancestor, had lived on a eclectic woodland diet including hard foods mixed with tree bark, fruit, leaves and other plants. Other research, reported upon by Everything Dinosaur in 2013, provided further insight into the dietary habits of early hominins.

To see the article on research into early hominin diets: From a Forest Diet to a Savannah Smorgasbord.

To read an article explaining how A. sediba came to be named: South African “Cradle Fossil” Named.

This new study carried out by an international team of researchers, including Professors Lee Berger and Kristian Carlson from the Evolutionary Studies Institute (ESI) at the University of the Witwatersrand, now shows that Australopithecus sediba did not have the jaw and tooth structure necessary to exist on a steady diet of hard foods. This may have important implications on how this species of australopith is viewed in terms of its evolutionary link to that line of hominins that eventually led to our own kind.

Bio-mechanical Study Indicates that A. sediba Did Not Have “Nutcracker Jaws”

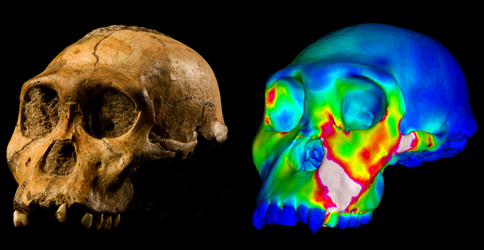

Picture credit: Image of MH1 by Brett Eloff provided courtesy of Lee Berger (University of the Witwatersrand).

Finite Element Modelling

The picture above show the fossilised skull of A. sediba (specimen number MH1) and a finite element model of the skull depicting strains experienced during a simulated bite on the its back teeth (premolars). “Warm” colours indicate high mechanical strain, whilst “cool” colours indicate areas of low strain on the skull.

Commenting on the research, published today in the scientific journal “Nature Communications”, Professor David Strait (Washington University, St Louis, USA) stated:

“Most australopiths had amazing adaptations in their jaws, teeth and faces that allowed them to process foods that were difficult to chew or crack open. Among other things, they were able to efficiently bite down on foods with very high forces.”

Co-author Dr Justin Ledogar, researcher at the University of New England in Australia added:

“Australopithecus sediba is thought by some researchers to lie near the ancestry of Homo, the group to which our species belongs, yet we find that A. sediba had an important limitation on its ability to bite powerfully; if it had bitten as hard as possible on its molar teeth using the full force of its chewing muscles, it would have dislocated its jaw.”

Not Bitting Off More Than It Could Chew

Bio-mechanical modelling based on a computer generated replica of the fossil skull material does not provide conclusive evidence that Australopithecus sediba was on the direct evolutionary line towards Homo, but it does indicate that dietary changes were shaping the evolutionary paths of early human species. The data acquired from the bio-mechanical analysis does not dispute the possibility that A. sediba occasionally ate hard foods such as nuts and bark. However, limitations on the amount of bite force that the skull could withstand suggests that hard foods needing to be processed with high bite forces were not an important component of the diet of this species.

About Australopithecus sediba

Australopithecus sediba, a diminutive pre-human species that lived about two million years ago in southern Africa, has been heralded as a possible ancestor or close relative of Homo, our own family. Australopiths appear in the fossil record about four million years ago, and although they have some human traits such as the ability to walk upright on two legs, most of them lack other characteristically human features such as a large brain, flat faces with small jaws and teeth, and advanced use of tools. Humans, members of the genus Homo, are almost certainly descended from an Australopith ancestor, and A. sediba is a candidate to be either that ancestor or something similar to it.

Dr Justin Ledogar explained:

“Humans also have this limitation on biting forcefully and we suspect that early Homo had it as well, yet the other Australopiths that we have examined are not nearly as limited in this regard. This means that whereas some Australopith populations were evolving adaptations to maximise their ability to bite powerfully, others (including A. sediba) were evolving in the opposite direction.”

Foods that were important to the survival of Australopithecus sediba probably could have been eaten relatively easy without the need for high bite forces.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the support of the University of Witwatersrand in the compilation of this article.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s award-winning website: Everything Dinosaur.