Giant Kangaroos Made for Walking

Giant Sthenurine Kangaroos Probably Walked Rather Than Hopped

The Pleistocene prehistoric fauna of Australia may not quite be as embedded into the public’s consciousness as the Woolly Mammoths, Cave Bears and Sabre-toothed cats that represent examples of European Pleistocene prehistoric animals, but if anything, ancient “Aussies” were even more amazing than the shaggy coated examples typical of the fauna of the western hemisphere.

Giant Kangaroos

In a new study, published in the on line academic journal PLOS One (Public Library of Science), a team of researchers propose that ancient, giant Australian Kangaroos were walkers rather than hoppers, making up part of a prehistoric fauna that was truly astonishing.

The Kangaroos in question are the heavy-weight members of the Sthenurinae (the short-faced kangaroos). A sub-family of the Macropodidae (means “big feet”), the family to which all Kangaroos belong. Following a rigorous comparative analysis, the research team conclude that these large animals, some of which stood over two metres tall, did not hop but were adapted to a pedestrian lifestyle, these animals were walkers.

Sadly, like most of Australia’s mega fauna these herbivores became extinct and did not make it into the Holocene. The last of the Sthenurinae died out about 30,000 years ago, shortly before the last of the Neanderthals in western Europe.

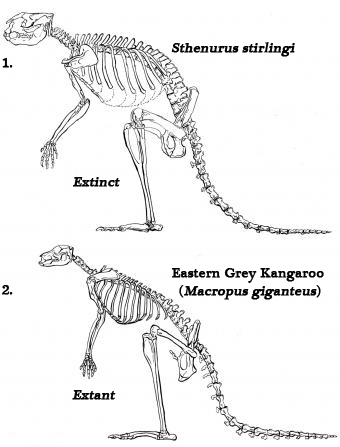

A Comparison Between an Extant Sthenurinae Kangaroo (Sthenurus stirlingi) and a Large Extant Species

Picture credit: Wells and Tedford, 1995. Original artist Lorraine Meeker, American Museum of Natural History, with additional annotation from Everything Dinosaur

Extinction Theories

As for reasons for their extinction, that question remains to be answered, however, it is thought that the presence of man on the continent from around 60,000 years ago had a severe impact on the fauna of Australia. Giant Short-faced Kangaroos such as Simosthenurus occidentalis (short-faced, strong tail, western Kangaroo), known from fossils found in south-western Australia, probably could not move very quickly and could be caught by human hunters. The use of fire could also have devastated their forest habitats leaving these browsers with little food.

The research team was led by Professor Christine Janis, (Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Brown University, Rhode Island, USA). Over one hundred comparative measurements were made, comparing the skeletons of living and extinct Kangaroo and Wallaby types. For Professor Janis, her eureka moment occurred in 2005. She was examining the bones of a mounted skeleton of a sthenurine Kangaroo in a Sydney museum when she noticed how inflexible the spine looked when compared to a modern-day counterpart. The professor began to wander whether these Pleistocene roos moved in the same way as extant Kangaroos.

Extinct Sthenurines

Working in collaboration with the papers co-authors, Borja Figuerido of the University of Malaga (Spain) and Karalyn Kuchenbecker, a former undergraduate at Brown University, the Professor spent several years examining the fossilised remains of extinct Kangaroos to determine their method of locomotion. In the published account of their studies, the team hypothesise that in their motion the extinct sthenurines were very different from large Kangaroos found today. The scientific paper is intriguing entitled: “Locomotion in Extinct Giant Kangaroos: Were the Sthenurines Hop-Less Monsters?”.

Extant Kangaroos can hop very quickly and utilise this unique form of motion to cover vast distances very efficiently. They can also move about on all fours as their front limbs are capable of helping to support bodyweight, an anatomical characteristic absent in the larger members of the Sthenurinae. The tail of many members of the Macropodidae is also able to bear weight, providing additional support for many Kangaroos and Wallabies. The use of the tail as a fifth limb has been referred to as a “pentapedal” stance. Extinct Kangaroos such as Sthenurus stirlingi seem to lack the flexible spine need to make leaps and bounds. Their anatomy seems best suited to putting one foot in front of the other – a walking Kangaroo!

Sthenurines had proportionally bigger hip and knee joints. The shape of the pelvic area differs significantly as well (see diagram above). The sthenurines had a broad and flared pelvis that would have allowed for proportionally much larger gluteal muscles than other Kangaroos. Those muscles would have allowed them to balance weight over just one leg at a time, as do the large gluteals of humans during walking.

One Massive Toe

Unlike modern Kangaroos with their four-toed feet, the extinct sthenurines had just one, massive toe on the end of each foot. The research team conclude that when the anatomy of all the Macropodidae is considered, the “weird” ones are the extant species that hop. They are very lightly built for their size and their preferred method of locomotion may not be typical for the group as a whole. A bit like using the Cheetah as a template for all Felidae motion.

Commenting on the research Professor Janis stated:

“If it is not possible in terms of biomechanics to hop at very slow speeds, particularly if you are a big animal and you cannot easily do pentapedal locomotion, then what do you have left? You have to move somehow.”

An over reliance on walking, which is not as efficient as hopping, might explain the demise of these Kangaroos about 30,000 years ago. These animals might have been easier to catch so humans took a toll on the population. Or as the climate became more arid, these walking Kangaroos were not able to migrate far enough to find new sources of food.

An Artist’s Impression of a Short-Faced Kangaroo

Picture credit: Brian Regal

The research team admit that more evidence is required to back up their anatomical study. Ideally, if a set of “walking Kangaroo” tracks could be discovered, that would add considerable weight to their hypothesis.