Nosing Around Dinosaurs with a New Study

New Study Sniffs Out Details of the Pachycephalosaur Nose

A study into the nasal passages conducted by a team of scientists from Ohio University suggests that certain types of dinosaur used their complicated noses to help cool their brains as well as to enhance their ability to smell. A new study has got to grips with the noses of dinosaurs.

The Noses of Dinosaurs

The study, which focused on specimens from the Pachycephalosauridae family (the bone-heads), involved the development of computer models derived from CT scans of fossilised skulls in order to map the airflow in and out of a dinosaur’s snout. Palaeontologists have known for some time that a number of different types of dinosaur had very complex nasal passages. The nasal region although mostly associated with breathing (respiration), also plays an important role in helping to define and enhance a creature’s sense of smell. In addition, the ability to bring in air at an ambient temperature into the skull may have a function in helping the brain to keep cool.

In the Late Cretaceous of North America, Pachycephalosaurs may have had small brains in their heavily armoured skulls but they did not want them to cook inside those thick heads.

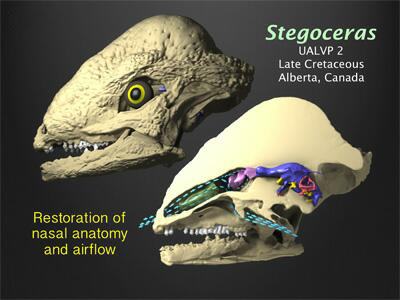

A Model of a Typical Member of the Pachycephalosauridae Family

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Lead author of the research, which has just been published in the academic journal “The Anatomical Record”, Jason Bourke (Ohio University) states:

“Figuring out what’s going on in their [dinosaurs] complicated snouts is challenging because noses have so many different functions. It doesn’t help that all the delicate soft tissues rotted away millions of years ago.”

Examining the Nasal Passages

In order to gain an appreciation of the nasal passages of long extinct dinosaurs, the team examined the snouts of extant relatives of the Dinosauria, namely birds, crocodiles and other reptiles including lizards. The study of fossil skulls of pachycephalosaurs was supported by lots of dissections, blood-vessel injections to map blood flow as well as CT scans. The researchers also relied upon computer models that provided a three-dimensional analysis of airflow.

A technique more commonly applied to the study of airflow in the aerospace industry, a technique called computational fluid dynamics was used to better understand how extant animals such as Alligators and Ostriches breathe.

As PhD student Jason Bourke explained:

“Once we got a handle on how animals breathe today, the tricky part was finding a good candidate among the dinosaurs to test our methods.”

The team turned to a family of bird-hipped dinosaurs known as the pachycephalosaurs, the bone-headed dinosaurs. These particular dinosaurs were chosen as a number of specimens were readily available to study in the United States/Canada and skulls attributed to several genera were known. The thick skulls with their ornamentation may have been used by these relatively small dinosaurs for head-butting or visual displays. The skull bones, some of which are several inches thick, has helped to preserve details of the nasal passages which the scientists were able to map and analyse in great detail.

Getting Up a Dinosaur’s Nose

Picture credit: Ohio University/The Anatomical Record

Studying Stegoceras

One pachycephalosaur that was studied was Stegoceras (S. validum) and the researchers were able to show that some of the airflow that they mapped would have carried odours to the olfactory region, helping to improve this dinosaur’s sense of smell. In addition, the team tried to piece together the shape of the nasal concha, otherwise known as the turbinates, that help to direct and manage airflow through the nasal passage. This small bone, superficially resembles a sea shell (hence the name) and the fossil evidence supports the presence of such a bone but it is not found in the Dinosauria fossil record (as far as we at Everything Dinosaur know).

As the researchers point out, there is the bony ridge preserved on pachycephalosaur skulls that indicate its presence and when airflow models were created, the best and most efficient ones produced included a turbinate structure within the model.

Commenting on the research results, Jason Bourke stated:

“We don’t really know what the exact shape of the respiratory turbinate was in Stegoceras, but we know that some kind of baffle had to be there.”

Study co-author Ruger Porter (Ohio University), pointed out that turbinates may well direct air to the olfactory region, but they might have also played another critical role, helping to cool the brain or at least helping to conserve moisture that might have been lost during exhalation.

Porter pointed out:

“The fossil evidence suggests that Stegoceras was basically similar to an Ostrich or an Alligator. Hot arterial blood from the body was cooled as it passed over the respiratory turbinates and then that cooled venous blood returned to the brain.”

Endothermic Implications?

Whether this new research supports the theory that these dinosaurs were warm-blooded (endothermic) is being debated, but it does suggest there was more going on within dinosaur’s noses than scientists had previously thought. It is hoped that the research team will be able to apply their analytical methods to other types of dinosaur such as the Thyreophora (armoured dinosaurs), known for their notoriously complex nasal passages. This research may also provide answers to the questions concerning the bizarre shape of many crests found in lambeosaurine dinosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs).

For models and figures of dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures: CollectA Prehistoric Life Models and Figures.