Dimetrodon with “Steak-knife” Teeth According to New Research

Serrated Teeth – The Secret of Dimetrodon’s Success

Long before the first dinosaurs evolved, one of the top terrestrial predators on the planet was Dimetrodon, the famous sail-backed reptile, a pelycosaur and now a new study by University of Toronto scientists suggests how this large carnivore was able to achieve apex predator status.

Dimetrodon

Graduate student Kirstin Brink, in collaboration with Professor Robert Reisz (University of Toronto), have studied the dentition (teeth) of a number of Dimetrodon species and they have discovered that these kinds of mammal-like-reptile were the first land living vertebrates to evolve ziphodont (serrated) teeth. The pointed, recurved and serrated teeth allowed Dimetrodon to tackle prey animals much larger than itself. The strong, reinforced skull and these knife-like teeth gave these reptiles a formidable bite, one that was capable of ripping and tearing flesh from their victim’s bodies.

An Illustration of Dimetrodon

Picture credit: Safari Ltd/Everything Dinosaur

To view models and replicas of Palaeozoic animals: Wild Safari Dinos and Prehistoric World Models.

Sail-backed Reptile

Dimetrodon is one of the easiest to recognise of all the prehistoric animals, thanks to its huge “sail” that rose up out of this animal’s back. This is a feature found in a number of pelycosaurs, although palaeontologists remain uncertain as to its exact role and function. Models of this Permian predator are often found in “dinosaur model sets” although the Dimetrodon genus was extinct millions of years before the first dinosaurs evolved. A synapsid reptile, Dimetrodon is actually more closely related to mammals than it is to the Dinosauria.

To read an article that attempts to explain why Dimetrodon is often regarded as a dinosaur: Dimetrodon – Often Mistaken for a Dinosaur.

Ziphodont Teeth

Although, most meat-eating theropod dinosaurs had ziphodont (serrated) teeth, this new study suggests that Dimetrodon spp. evolved dentition that was serrated over thirty-five million years before the first dinosaurs. The scientists used scanning electron microscopy to examine minute structures in the teeth of a Dimetrodon species, analysing specimens from the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum.

Several different species of Dimetrodon were included in the tooth study, the fossils spanning some twenty-five million years of the Permian geological period.

Dimetrodon Species

The scientists conclude that Dimetrodon spp. had a diversity of previously unknown tooth morphology including cusps (raised points on the crowns of the teeth), the dominant morphology of teeth in modern Mammalia. Intriguingly, the researchers suggest that as Dimetrodon spp. evolved into the likes of the giant Dimetrodon grandis, so serrated teeth evolved too.

Ziphodont tooth structures are absent in earlier species of the Dimetrodon genus. As the skull morphology remains relatively consistent across all the Dimetrodon species studied, it is the shape of the teeth that change, this indicates a gradual change in feeding habits.

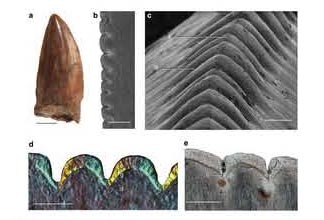

The Teeth of D. grandis Show “Tell-Tale” Serrations

Picture credit: University of Toronto

The picture shows a Dimetrodon grandis tooth specimen from the Royal Ontario Museum (Canada) (a), along with various scanning electron microscope images showing the serrations (b-e).

Professor Reisz explained:

“This research is an important step in reconstructing the structure of ancient, complex communities. Teeth tell us a lot more about the ecology of animals than just looking at the skeleton.”

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur commented:

“It is very likely that Dimetrodon species such as D. grandis were highly mobile, apex predators, this new study provides further insights into how these large reptiles came to dominate terrestrial environments of the Late Permian.”

Research into Dentition

The research into the dentition of Dimetrodon and the way in which the teeth evolved but the skull shape and structure remained relatively unchanged suggests a change in feeding style and trophic interactions. The term trophic, when used in biology, refers to feeding styles and nutrition. The researchers conclude that ziphodont teeth evolved in the larger species of Dimetrodon independently from the ziphodont teeth that has been recorded from later therapsids.

The likes of Dimetrodon grandis would certainly have been one animal best avoided during the Permian, Professor Reisz stated:

“The steak-knife configuration of these teeth and the architecture of the skull suggest Dimetrodon was able to grab and rip and dismember large prey. Teeth fossils have attracted a lot of attention in dinosaurs but much less is known about the animals that lived during this first chapter in terrestrial evolution.”