Rhamphorhynchus Falls Victim to Ganoid Fish

Scientists have frequently speculated how the likes of Rhamphorhynchus, a Late Jurassic, long-tailed pterosaur hunted fish. A remarkable fossil find from lithographic limestone deposits of Solnhofen (Germany) may add weight to the theory that these pterosaurs skimmed the surface of the water, snatching fish from the sea with their spiky-toothed jaws. There is certainly evidence in the fossil record to suggest that Rhamphorhynchus genera were piscivores (fish-eaters), however, this amazing fossil discovery also suggests that certain types of fish lurking in the anoxic (depleted of oxygen, thus aiding fossil preservation), waters of the lagoon were prepared to attack these flying reptiles and drag them to their doom.

Rhamphorhynchus

It seems that after a successful hunt, one unlucky pterosaur was grabbed by a predatory fish, a ganoid fish known as Aspidorhynchus acutirostris. These two fish-eaters became tangled up, the pterosaur drowned and unable to shake the Rhamphorhynchus out of its mouth, the Jurassic fish also met its demise.

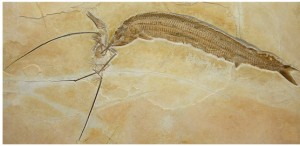

Pterosaur versus Ganoid Fish Preserved in the Fossil Record

Picture credit: PloS One/Frey, Tischlinger.

The picture above shows the flying reptile with its wing trapped in the fine teeth of the predatory fish. A number of fossils are known from the Solnhofen deposits were skull elements of ganoid fish are found in association with the remains of members of the Rhamphorhynchidae. Since the jaws of the fish could not open very wide, and since no pterosaur remains have been found in the stomachs of fossilised fish of this genus, it can be assumed that flying reptiles were not a normal prey item for this predator. Perhaps the water disturbance of a pterosaur skimming the surface water fishing attracted the attention of the larger fish, who inadvertently grabbed the Rhamphorhynchus as it flew passed.

Rhamphorhynchus is one of the best known of all the long-tailed pterosaurs. Several species have been identified, the largest of which had a wingspan about the size of the height of a man (nearly six feet). Fossils of the pterosaur have been found in strata associated with coastal areas. The teeth in the narrow jaws were long, pointed and interlocked when the jaws were closed indicating that this pterosaur was probably a hunter of fish, this new fossil discovery indicates that sometimes, inadvertently at least, Rhamphorhynchus became the hunted.

An Illustration of a Rhamphorhynchus

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

For models and replicas of Rhamphorhynchus and other pterosaurs: Wild Safari Pterosaur and Dinosaur Models.

Evidently, the flight membrane of the reptile, jammed in the teeth of the fish. Evidently, the fish could not swallow the pterosaur due to its size and bulky skeleton. Furthermore, ganoid fishes like Aspidorhynchus have skulls with limited kinetic options such that they were not suitable to manipulate prey that exceeded the standard gape of the jaws. So for the fish, it could not swallow its victim, nor could it free itself from the wing membrane.

The authors of the paper on this remarkable fossil find (paper published in the “Public Library of Science – Biology”), suggest that the aktinofibrils of the tough and leathery wing membrane of the pterosaur got jammed between the densely packed teeth of the fish. Like most extant fish Aspidorhynchus had no other possibility to get rid of its unwanted victim than trying to shake it loose or swimming rapidly and trying spinning or twisting manoeuvres. That the fish in fact tried to get rid of its unwanted meal by vigorous movements of its head is evidenced by the distortion of the left wing finger elements, while the remaining skeleton of the Rhamphorhynchus lies in natural articulation. This is one Jurassic encounter that ended fatally for both participants.

Vertebrate skeletons from different creatures found together is exceedingly rare in the fossil record. A number of fossils found at Solnhofen reveal this unfortunate relationship between Rhamphorhynchus and ganoid fish, but this specimen provides scientists with supporting evidence with regards to the feeding methods of the flying reptile. Lodged in the throat of the pterosaur are the fossilised remains of a small Leptolepidid fish. The pterosaur also has fish bones in its stomach. The undigested state of the fish in the throat suggests that the Rhamphorhynchus was seized during or immediately after a successful hunt.

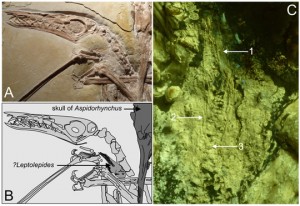

Evidence of Rhamphorhynchus Hunting Fish

Picture credit: PloS One/Frey, Tischlinger.

The picture shows a photograph (close up) of the jaws and throat of the Rhamphorhynchus (A), a line drawing showing the position of the small fish the pterosaur swallowed (B) and a close up of the tiny fish fossil viewed under filtered ultraviolet light which shows up greater detail than natural light (C).

In the PloS One journal the pictures are described, the straight vertebral column and the closed tail fin, which is orientated towards the mouth cavity suggests that the fish was not regurgitated during the agony of the pterosaur. Furthermore the prey does not show any trace of digestion. A) photograph of the specimen WDC CSG 255 showing the position of the Leptolepides? in the throat of the flying reptile. To the right hand side the skull of the ganoid fish predator visible. B) line drawing of (A), C) close-up of Leptolepides? under filtered UV light: 1 caudal fin, 2 neural spines, 3 vertebral column.

To read more about the theory regarding how pterosaurs such as the Rhamphorhynchidae may have hunted: Pterosaur Feeding Habits – Could they Skim the Water for Fish?

Solnhofen deposits outcrop in an east-west belt north of Munich (Germany), they have produced some exquisite fossils, a record of the flora and fauna of a Jurassic lagoonal environment. This remarkable fossil helps to add to our knowledge about vertebrate interactions that took place in that shallow water environment all those millions of years ago.

The scientific paper: “The Late Jurassic Pterosaur Rhamphorhynchus, a Frequent Victim of the Ganoid Fish Aspidorhynchus?” by Eberhard Frey and Helmut Tischlinger published in PLoS One.

Leave A Comment