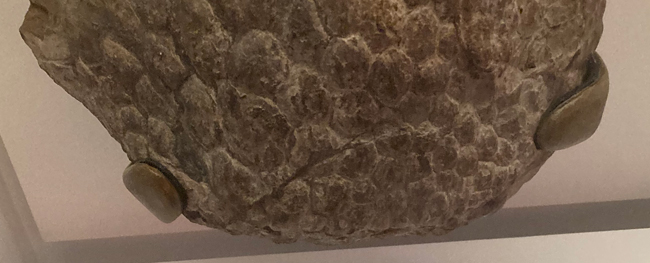

Team members photographed a sauropod skin impression whilst visiting the London Natural History Museum. The specimen is part of the Patagotitan exhibition entitled “Titanosaur – Life as the Biggest Dinosaur”. Although most visitors probably overlook this fossil it is perhaps one of the most important fossil specimens on display in this part of the museum.

A detailed analysis of the skin impression provided new information on the anatomy of sauropods. A study revealed features on the skin that might explain how these dinosaurs were able to grow so big.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Studying a Sauropod Skin Impression

This is a fossilised imprint of sauropod skin. It is specimen number NHMUK R1868. It was the first skin impression to be described in any non-avian dinosaur. The fossil, discovered in 1852 provided the first evidence that sauropods had scaly skin. The impression was formed when the skin of a carcase was pressed into soft mud. This left an impression of the skin contours imprinted on the sediment. Over millions of years the ground hardened into rock.

The fossil was discovered in Hastings along with a large forelimb. The material comes from the Hasting Beds, which are part of the Wealden Group and represent Lower Cretaceous deposits. The sauropod, possibly a basal titanosaur, has been named Haestasaurus becklesii. The skin impression is thought to have come from the forearm, the presence of smaller scales at one end of the specimen suggests that the skin impression might have come from the elbow area. The smaller scales would have permitted greater flexibility in the joint.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The image above shows the recently introduced Wild Safari Prehistoric World Patagotitan dinosaur model.

To view this range of prehistoric animal figures: Wild Safari Prehistoric World Models.

A Sauropod Skin Scientific Paper

A paper published in February 2022 (Pittman et al) examined NHMUK R1868 in detail using laser-simulated fluorescence (LSF). This technique reveals much more detail at the microscopic level than exposure to normal light and UV light. The researchers discovered that the skin was covered in tiny bumps (papillae). These convex bumps increased the surface area of the skin, and it was thought that they played a role in thermoregulation.

Large animals, such as sauropods need to find ways to stop their bodies overheating. The extended surface area of their long necks and tails would have helped, but the researchers speculate that these small bumps greatly increased the skin surface area, thus permitting more efficient heat exchange between their bodies and the environment.

A review of other sauropod skin fossils demonstrated that intrascale papillae were unique to and widespread across the Neosauropoda. This suggests that this trait evolved early in the Sauropoda, and it might explain why these types of dinosaurs were able to grow so big and to become giants.

The scientific paper: “Newly detected data from Haestasaurus and review of sauropod skin morphology suggests Early Jurassic origin of skin papillae” by Michael Pittman, Nathan J. Enriquez, Phil R. Bell, Thomas G. Kaye and Paul Upchurch published in Communications Biology.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment