The first tetrapods (land living animals) were amphibious. It had been thought that the development of an egg with a semi-permeable shell (amniote egg) was a fundamental step in the development of life on land. This adaptation meant that land animals did not have to return to water to breed and spawn. Freed from having to return to the water, early tetrapods could explore new environments and expand into new habitats.

However, a new paper written by researchers from Nanjing University (China) and the University of Bristol challenges this view of evolution.

The researchers conclude that the earliest reptiles, birds and mammals (Amniota), may have borne live young.

What is an Amniote?

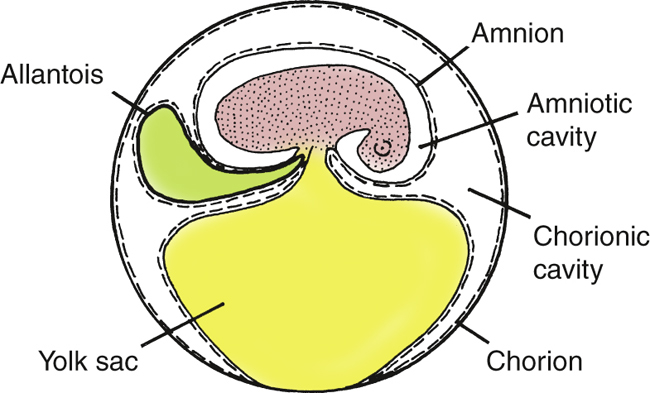

Amniotes lay eggs that have a semi-permeable shell that protects the embryo from drying out. A tough, internal membrane called the amnion surrounds the growing embryo as well as the yolk, the food source. Development of the embryo in a shelled egg meant that for the first time in history, the tetrapods were no longer tied to water to breed. We as mammals are amniotes, along with the birds and reptiles.

Studying Extinct and Extant Species

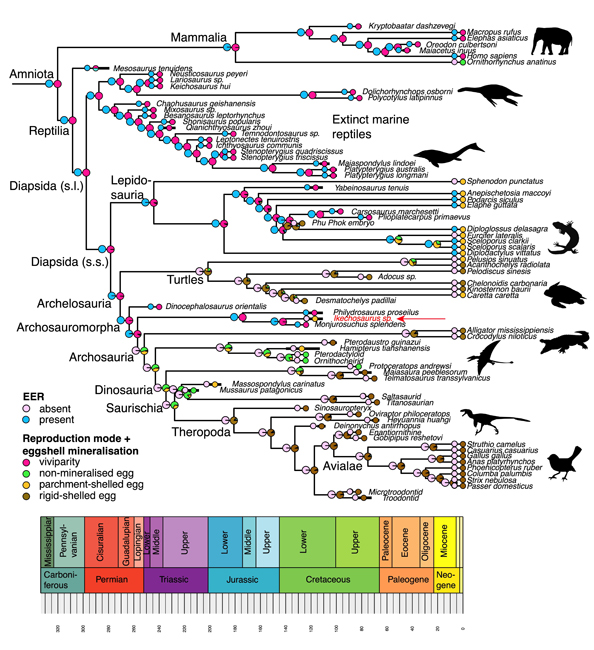

However, a study of 51 fossil species and 29 living species which could be categorised as oviparous (laying hard or soft-shelled eggs) or viviparous (giving birth to live young) suggests that the earliest reptiles, mammals and birds probably were capable of bearing live young.

The findings, published today in the academic journal “Nature Ecology & Evolution”, show that all the great evolutionary branches of the Amniota, the Mammalia, Lepidosauria (lizards and relatives), and the Archosauria (dinosaurs, crocodilians, birds) reveal viviparity and extended embryo retention in their ancestors.

To read an Everything Dinosaur blog post about research suggesting that an ancestor of the dinosaurs may have been a live-bearer: First Live Birth Evidence in Ancient Dinosaur Relative.

Extended Embryo Retention (EER)

Extended embryo retention (EER) occurs when the young are retained by the mother for a varying amount of time, likely depending on when conditions are best for survival. While the hard-shelled egg (amniote egg), has often been seen as one of the greatest innovations in evolution, this research implies it was extended embryo retention that gave this particular group of animals the ultimate protection.

Professor Michael Benton (School of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol) explained:

“Before the amniotes, the first tetrapods to evolve limbs from fishy fins were broadly amphibious in habits. They had to live in or near water to feed and breed, as in modern amphibians such as frogs and salamanders.”

Professor Benton added:

“When the amniotes came on the scene 320 million years ago, they were able to break away from the water by evolving waterproof skin and other ways to control water loss. But the amniotic egg was the key. It was said to be a “private pond” in which the developing reptile was protected from drying out in the warm climates and enabled the Amniota to move away from the waterside and dominate terrestrial ecosystems.”

Challenging the Standard View About Amniote Egg Evolution

Project leader and corresponding author Professor Baoyu Jiang (Nanjing University) stated:

“This standard view has been challenged. Biologists had noticed many lizards and snakes display flexible reproductive strategy across oviparity and viviparity. Sometimes, closely related species show both behaviours, and it turns out that live-bearing lizards can flip back to laying eggs much more easily than had been assumed.”

Many Marine Reptiles were Live-bearers

Co-author Dr Armin Elsler (University of Bristol) commented:

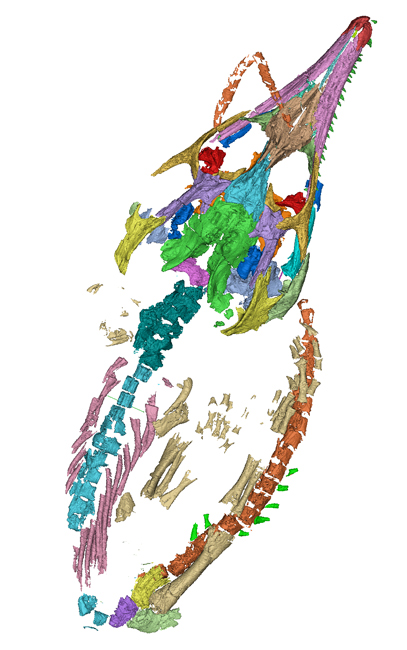

“Also, when we look at fossils, we find that many of them were live-bearers, including the Mesozoic marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs. Other fossils, including a choristodere from the Cretaceous of China, described here, show the to-and-fro between oviparity and viviparity happened in other groups, not just in lizards.”

The picture (above) shows the CollectA Age of Dinosaurs Popular Temnodontosaurus model. The ichthyosaur is giving birth, demonstrating viviparity within the Ichthyosauria.

To view the range of CollectA not-to-scale models available from Everything Dinosaur: CollectA Age of Dinosaurs Popular Figures.

Delaying the Birth

In many types of extant vertebrate extended embryo retention (EER) is quite common. The developing young are retained by the mother for a lesser or greater span of time. The mother delays giving birth until conditions are most favourable to permit the survival of her offspring. The mother deliberately gives birth at the most propitious time.

Co-author of the paper, Dr Joseph Keating commented:

“EER is common and variable in lizards and snakes today. Their young can be released, either inside an egg or as little wrigglers, at different developmental stages, and there appears to be ecological advantages of EER, perhaps allowing the mothers to release their young when temperatures are warm enough and food supplies are rich.”

Profound Implications for our Understanding of Tetrapod Evolution

Professor Benton summarised the study:

“Our work, and that of many others in recent years, has consigned the classic ‘reptile egg’ model of the textbooks to the wastebasket. The first amniotes had evolved extended embryo retention rather than a hard-shelled egg to protect the developing embryo for a lesser or greater amount of time inside the mother, so birth could be delayed until environments become favourable.”

The professor implied that this study had profound implications for our understanding of tetrapod evolution. He added:

“Whether the first amniote babies were born in parchment eggs or as live, snapping little insect-eaters is unknown, but this adaptive parental protection gave them the advantage over spawning earlier tetrapods.”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Bristol in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Extended embryo retention and viviparity in the first amniotes” by Baoyu Jiang, Yiming He, Armin Elsler, Shengyu Wang, Joseph N. Keating, Junyi Song, Stuart L. Kearns and Michael J. Benton published in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment