The giant prehistoric rhino, Paraceratherium, is considered the largest land mammal that ever lived. It was mainly found in Asia, especially China, Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Pakistan. How these giant, hornless rhinos dispersed across Asia was unknown, but the discovery of fossils in Gansu Province, has led to the naming of a new Paraceratherium species (Paraceratherium linxiaense) and shed light on how these amazing herbivores evolved and dispersed across the Asian continent.

Providing Important Clues About Paraceratherium Dispersal

Writing in the academic journal “Communications Biology”, the researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Hezheng Paleozoological Museum (Gansu Province), Henan University (Henan Province) and Harvard University describe fossils found near the village of Wangjiachuan (Gansu Province) in 2015 that enabled the establishment of a new species of Paraceratherium.

Analysis of the fossil material led the scientists to conclude that this new species was closely related to giant rhinos that once lived in Pakistan (Paraceratherium bugtiense), which suggests ancestral forms migrated across Central Asia.

The Remarkable Fauna of the Linxia Basin in the Late Oligocene

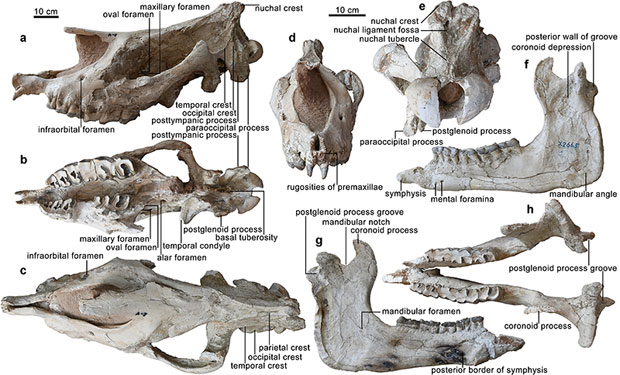

The fossil material which includes a skull and articulated mandible as well as the first cervical vertebra (atlas), as well as another neckbone and two thoracic vertebrae from a second individual were found in Late Oligocene deposits associated with the Jiaozigou Formation of Linxia Basin (Gansu Province), close to the north-eastern border of the Tibetan Plateau.

Around 26.5 million years ago, the open woodland environment of north-central China was home to a wide variety of prehistoric mammals including the giant rhinos Turpanotherium and Dzungariotherium, the rodent Tsaganomys, the creodont Megalopterodon, the chalicothere Schizotherium, the hyracodont Ardynia, the rhinocerotid Aprotodon, and the entelodont Paraentelodon – some of these animals are illustrated in the Paraceratherium linxiaense life reconstruction (above).

Standing taller than a giraffe and weighing approximately 20 tonnes, Paraceratherium linxiaense had a slender skull and a prehensile nose trunk similar to that of the modern tapir to help it to grab leaves and branches from the tops of trees, a food resource that no other animal in its environment could exploit.

Plotting the Distribution and Dispersal of Paraceratherium

A phylogenetic analysis carried out by the research team suggests P. linxiaense as a derived form with a mix of basal and more advanced traits. The phylogenetic analysis produced a series of progressively more-derived species from P. grangeri, through P. huangheense, P. asiaticum, and P. bugtiense before finally terminating in P. linxiaense and what is thought to be its sister taxon P. lepidum.

The research team conclude that Paraceratherium linxiaense was a more specialised animal, with a more flexible neck, similar to P. lepidum, and both are derived from Paraceratherium bugtiense known from Pakistan. They team were then able to plot and map the spread of these giant rhinos across Asia.

The researchers found that all six species of Paraceratherium are sister taxa to the hornless rhinoceros Aralotherium which is known from Kazakhstan and China and form a monophyletic clade in which P. grangeri is the most primitive, succeeded by P. huangheense and P. asiaticum.

The researchers were thus able to determine that, in the Early Oligocene, P. asiaticum dispersed westward to Kazakhstan and its descendant lineage expanded to South Asia as Paraceratherium bugtiense. In the Late Oligocene, Paraceratherium returned northward, crossing the Tibetan region, which implies that this area of Asia was not yet uplifted to form a high, difficult to traverse plateau. This migration led to two distinct species evolving P. lepidum to the west in Kazakhstan and P. linxiaense to the east in the Linxia Basin.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Contrasting the high altitude of the Tibetan region today to the environment of this region during the Late Oligocene Epoch, lead author of the research Professor Deng Tao explained that:

“Late Oligocene tropical conditions allowed the giant rhino to return northward to Central Asia, implying that the Tibetan region was still not uplifted as a high-elevation plateau.”

During the Oligocene, the giant rhino could disperse freely from the Mongolian Plateau to South Asia along the eastern coast of the Tethys Ocean and perhaps through Tibet. Up to the Late Oligocene, the evolution and migration from P. bugtiense to P. linxiaense and P. lepidum demonstrates that the “Tibetan Plateau” was not yet a barrier to the movement of the largest land mammal known to science.

The scientific paper: “An Oligocene giant rhino provides insights into Paraceratherium evolution” by Tao Deng, Xiaokang Lu, Shiqi Wang, Lawrence J. Flynn, Danhui Sun, Wen He and Shanqin Chen published in Communications Biology.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Preshistoric Animal Models and Figures.

Leave A Comment