One Very Flashy New Dinosaur – Ubirajara jubatus

Ubirajara jubatus – One Very Flashy Dinosaur

A new genus of feathered dinosaur Ubirajara jubatus has been described.

News about the discovery of a species of feathered dinosaur has now become relatively commonplace. Yet, it is worth remembering that it was just twenty-four years ago, back in 1996, that the first, non-avian dinosaur species with evidence of fuzzy feathers was described. Named Sinosauropteryx this lithe meat-eater literally “rocked” scientists as the long-awaited proof of feathered dinosaurs was revealed to the world. Sinosauropteryx was a compsognathid, a team of researchers, including scientists from the University of Portsmouth have described another feathered dinosaur, this new feathered theropod is a compsognathid too, but with a more elaborate and spectacular integumentary covering.

Ubirajara jubatus

The newly described Ubirajara jubatus is the first Gondwanan non-avian theropod with preserved filamentous integumentary structures. It is also the first non-maniraptoran possessing elaborate integumentary structures that were most likely used for display.

A Life Reconstruction of the Newly Described Brazilian Compsognathid Ubirajara jubatus

Picture credit: Bob Nicholls/Paleocreations

Dressed to Impress

Described as the most elaborately dressed-to-impress dinosaur described to date, the research team co-led by Professor David Martill and researcher Robert Smyth (University of Portsmouth), propose that U. jubatus will shed new light on how birds evolved elaborate display structures.

This chicken-sized dinosaur possessed a mane of long bristles running down its back and stiff ribbons projecting out and back from its shoulders, a combination of features never seen before in the fossil record.

The scientific paper has been published in the journal of Cretaceous research and involved a collaboration between the University of Portsmouth and the appropriately named Professor Dino Frey at the State Museum of Natural History, Karlsruhe, Germany, who discovered the new species while examining fossils in Karlsruhe´s collection and Héctor E. Rivera-Sylva of the Departamento de Paleontología, Museo del Desierto in Saltillo, Mexico. The fossil was authorised by the Brazilian authorities for export some time ago, but was only recently studied.

Bizarre Integumentary Structures

The bizarre integumentary structures must have had a purpose, whilst the body covering may have originally evolved to provide insulation, the stiff ribbons on either side of the shoulders were probably used for display, perhaps to attract a mate, deter a rival or to frighten a potential predator.

Professor Martill commented:

“We cannot prove that the specimen is a male, but given the disparity between male and female birds, it appears likely the specimen was a male, and young, too, which is surprising given most complex display abilities are reserved for mature adult males. Given its flamboyance, we can imagine that the dinosaur may have indulged in elaborate dancing to show off its display structures.”

Not Scales or Fur

The ribbons are not fur or scales, they are not feathers in the modern sense, as seen on an extant bird. They appear to be structures unique to this animal.

Mr Smyth added:

“These are such extravagant features for such a small animal and not at all what we would predict if we only had the skeleton preserved. Why adorn yourself in a way that makes you more obvious to both your prey and to potential predators? The truth is that for many animals, evolutionary success is about more than just surviving, you also have to look good if you want to pass your genes on to the next generation.”

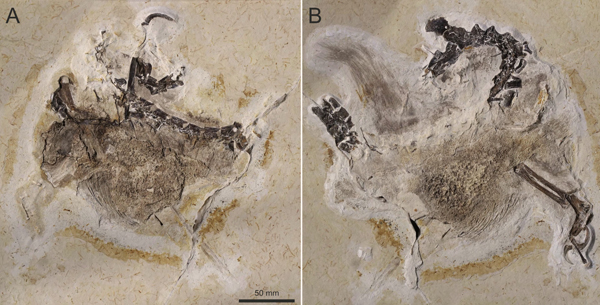

The Holotype of Ubirajara jubatus Preserved as a Slab and Counter Slab

Picture credit: Smyth et al /Cretaceous Research

From the Lower Cretaceous (Aptian) Crato Formation of North-eastern Brazil

Fossil discoveries starting with the ground-breaking Sinosauropteryx specimen that was described in 1996 have fundamentally changed our understanding of the phylogenetic relationships between birds and dinosaurs as well as the origin and evolution of feathers. A variety of elaborate integumentary coverings and structures are now known from the Theropoda and from ornithischian dinosaurs too. They have been linked to behaviours including egg incubation, mating displays and thermoregulation.

The Colourful PNSO Model of the Chinese Compsognathid Sinosauropteryx

The picture (above) shows a PNSO Sinosauropteryx dinosaur model.

To view the range of PNSO models and figures: PNSO Age of Dinosaurs Models.

Within the Theropoda, such features have only been previously recorded within the Maniraptoriformes, a theropod clade which includes birds and is defined as “the most recent common ancestor of the ostrich mimic Ornithomimus and Aves (birds) and all descendants of that common ancestor.”

The majority of theropods preserving integumental structures come from the Upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous of China or the Upper Jurassic of southern Germany and all are of Laurasian origin. Ubirajara jubatus from the Lower Cretaceous (Aptian) Crato Formation of north-eastern Brazil, is the first non-maniraptoran possessing elaborate integumentary structures that were most likely used for display.

Ubirajara jubatus the First Non-avian Theropod with Preserved Filamentous Structures

It is also the first non-avian theropod with preserved filamentous integumentary structures to have been described from the southern hemisphere landmass of Gondwana.

The researchers compare Ubirajara to living birds stating that many modern Aves are famed for their exotic and colourful plumage along with their complex displays that are used to win mates. Male peacocks with their stunning tails and male birds of paradise are examples of this.

Ubirajara jubatus (pronounce You-bi-rah-jar-rah jew-bay-tus), lived approximately 110 million years ago (Aptian faunal stage of the Early Cretaceous). The genus name is derived from the local Tupi dialect and translates as “lord of the spear”, whilst the trivial or specific name is from the Latin for “mane” a reference to the integumentary covering on its back.

Able to Raise its Hackles Like a Dog?

The mane running down its back is thought to have been controlled by muscles allowing it to be raised, in a similar way a dog raises its hackles or a porcupine raises its spines when facing a threat. Once the danger had passed, Ubirajara could lower its mane close to the skin allowing this little dinosaur to move quickly through the undergrowth without getting tangled up.

Professor Martill explained:

“Any creature with movable hair or feathers as a body coverage has a great advantage in streamlining the body contour for faster hunts or escapes but also to capture or release heat.”

The unique body plan of Ubirajara with its long, flat, stiff shoulder ribbons of keratin, each with a small sharp ridge running along the middle, described by the authors as “enigmatic” might have looked cumbersome, but in reality they were located on the body in such a way as not to impede movement allowing Ubirajara to preen, hunt, move around and display unencumbered.

The scientific paper: The scientific paper: “A maned theropod dinosaur from Gondwana with elaborate integumentary structures” by Robert S. H. Smyth, David M. Martill, Eberhard Frey, Héctor E. Rivera-Sylva and Norbert Lenz published in Cretaceous Research. This paper was withdrawn in July 2022.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.com