New Study Might Help Explain Why Crocodilians Survive Extinction Events

A team of scientists including researchers from the Natural History Museum (London) and the Milner Centre for Evolution (Bath University), have provided fresh insight into how crocodilians are able to survive dramatic changes in climate that cause extinctions amongst other vertebrates. The researchers conclude that extant crocodilians are part of a lineage of great survivors that might cope better than most other large animals when having to face a world with a continuing rise in average annual temperature.

Crocodilians Might Be Better Able to Cope with Global Climate Change

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Crocodiles Surviving Mass Extinction Events

Writing in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, the scientists suggest that the ability of crocodilians to survive mass extinction events could be due in part, to their approach to reproduction. Modern crocodiles are an ancient lineage. They are grouped into the clade Neosuchia, which first arose in the Late Cretaceous, although related forms are even older, such as the Pseudosuchia, which first arose some 250 million years ago.

Neosuchian crocodilians have therefore survived numerous extinction events, including two mass extinctions, the first that occurred approximately 66 million years ago and saw the demise of their fellow archosaurs – the Dinosauria and the Pterosauria as well as many other different types of organism. Then, there was a second, albeit smaller, mass extinction event towards the end of the Eocene approximately 33.9 million years ago.

The Relationship Between Size of Female Crocodilians and Where They are Found

The relationship between distribution patterns and body size has been recorded and analysed in many kinds of endothermic (warm-blooded) animals. However, evidence to support the idea that there is a correlation between where in the world animals are found and the size of females in ectotherms (cold-blooded animals), has been generally, not that well documented.

No extensive study between the global distribution of crocodiles and the body mass of females has been carried out. The research team examined the relationship between latitudinal distribution and body mass in twenty living species of crocodilians and studied seven other important factors in reptile reproduction such as size of the egg clutch laid, the number of successful hatchings per nest, incubation length and incubation temperature.

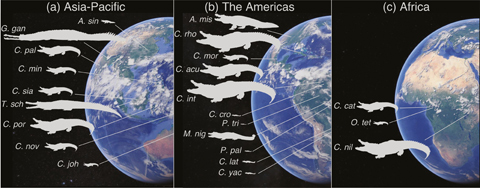

The Average Size of a Female of the Species was Correlated Against the Latitudinal Midpoint of Where that Species is Found

Picture credit: Lakin et al (Biological Journal of the Linnean Society)

Statistical Analysis

Using statistical analysis, the study showed that, in general, smaller species of crocodilian tend to live at low latitudes (close to the equator). Larger species tend to live at higher latitudes, still in the tropics but further away from the equator. This is the first study to propose a relationship between where in the world crocodilians live and the effect on adult female body mass.

Previous studies looking at the how well adapted crocodilians are have cited diet, their aquatic nature and their behaviours as factors in helping these types of creatures to survive dramatic changes in environmental conditions. However, this study also identified a unique aspect of crocodilian reproductive biology that may also be a significant factor.

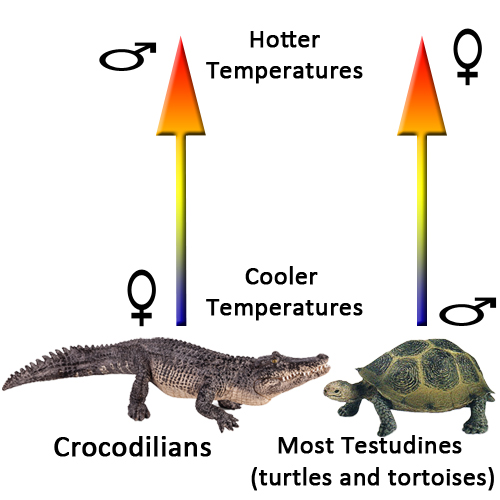

Crocodilians have no sex chromosomes, just like many types of tortoises and turtles, instead the sex of the hatchlings is determined by the temperature at which the eggs are incubated. Both crocodiles and most turtles have a threshold temperature at which the ratio of males to females is roughly equal in any given clutch.

Temperature and Crocodiles

In crocodilians, the higher the temperature of the clutch, then more males will be produced. For those members of the Order Chelonia (Testudines), that are biologically subject to temperature controlled sexual determination, the opposite is true, higher temperatures result in more female hatchlings. The increase in average global temperatures is already having a dramatic impact on turtle populations. Our warming world is resulting in some hatchling populations being comprised of 80% females. Such an imbalance in animal populations could have a dramatic impact on those species affected.

Environmental Temperature Affects the Sex of Crocodilians and Most Members of the Order Testudines

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The diagram (above), demonstrates that in crocodilians the higher the temperature of the nesting environment, more males are likely to be produced from the nest. For most members of the Order Testudines, the reverse is true – warmer temperatures will lead to more females.

The research team wanted to assess the impact of this aspect of crocodilian reproductive biology on their ability to cope with the impact of climate change.

Twenty Different Species of Crocodile Studied

In total, twenty different species of crocodiles were assessed to see if there was a correlation between their latitude and a variety of biological traits such as female body size and incubation temperature. The researchers conclude (with some exceptions), that smaller species do tend to live close to the equator, whilst larger species generally live in more temperate climates at higher latitudes. Intriguingly, they found that, in contrast to most Testudines, the threshold incubation temperatures don’t correlate with the latitude.

Whilst turtles are critically endangered by the increase in temperatures due to climate change, this research indicates that crocodiles and their close relatives may be slightly more resilient because of the ways they look after their young. For example, sea turtles always return to the same beach to nest and lay eggs regardless of the local environmental conditions, leaving their young to hatch alone and fend for themselves.

The authors hypothesise that the geographical location of the nest doesn’t affect the incubation temperatures as much as in turtles because crocodilians select their nesting sites carefully and bury their nests in rotting vegetation or earth which insulates them against temperature fluctuations.

However, despite being around virtually unchanged for 90 million years, crocodilians are still threatened and several species are critically endangered. Unless adequate steps are taken to safeguard these species, they too, will sadly, end up going the same way as the dinosaurs.

Keystone Species

Lead author of the study, PhD student Rebecca Lakin at the Milner Centre for Evolution (University of Bath) stated:

“Crocodilians are keystone species in their ecosystems. They are amongst the last surviving archosaurs, a group that once inhabited every continent and has persisted for at least 230 million years”.

Rebecca added:

“They show a remarkable resilience to cataclysmic climate change and habitat loss, however half of all living crocodile species are threatened with extinction and the rate of vertebrate species loss will soon equal or even exceed that of the mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs. Whilst their parenting skills and other adaptations brace them for climate change, they aren’t immune. They are still vulnerable to other human-induced threats such as pollution, the damming of rivers, nest flooding and poaching for meat or skin. Climate change could encourage these great survivors to relocate to other areas that are close to densely human populated areas, putting them at even greater threat.”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the Milner Centre for Evolution in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “First evidence for a latitudinal body mass effect in extant Crocodylia and the relationships of their reproductive characters” by Rebecca J Lakin, Paul M Barrett, Colin Stevenson, Robert J Thomas and Matthew A Wills published in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment