The Daohugou Biota – China 160 Million Years Ago

A team of international researchers based at the Chinese Academy of Sciences have identified a stratigraphic sequence of Middle Jurassic deposits thanks to fossils of a salamander. The huge assemblage of vertebrate fossils and other material has provided scientists with an exquisite insight into an ecosystem that thrived in north-eastern China around 160 million years ago. The series of highly fossiliferous sites are being linked into one large group of sedimentary material that can be put together in terms of their geological age thanks to the common range of fossils these different locations contain.

Sequence of Deposition

The locations (six in total scattered across the provinces of Hebei and Liaoning), are described as the Daohugou Biota. They form part of the Tiaojishan Formation (or at least most of the locations seem to do so), but importantly, the strata has been recognised as being much older than the Jehol Biota. The Jehol Biota is associated with Lower Cretaceous deposits (Barremian and Aptian stages of the Early Cretaceous), however, the Daohugou Biota is dated to around the Bathonian faunal stage of the Middle Jurassic.

The Jehol Biota

The Jehol Biota epitomised by the wonderfully well preserved fossil remains of Liaoning Province, is famous for its feathered primitive bird and feathered theropod dinosaur fossils representing an ecosystem that consisted of a series of large lakes, forests and nearby volcanoes. Periodically, the volcanoes would erupt, bury large areas of the surrounding landscape with ash and devastate the fauna and flora.

The fine grain sediments that were deposited helped preserve fossils in amazing detail. At first, all the fossils from this part of China were thought to be of Lower Cretaceous age, after all, such beautifully preserved fossils are exceptionally rare, but it now seems that prior to the environment which formed the Jehol Biota and fossil assemblage, there existed in the same location but around 30 million years earlier another ecosystem which has been preserved in equal detail thanks again to volcanic activity.

Identifying the Biota

Just like their Jehol Biota counterparts, the Daohugou theropod dinosaurs are feathered, with a lot of anatomical detail preserved thanks to the fine lacustrine (lake) beds in which the fossils are found. Something like 142 different vertebrate species have been identified from the Jehol Biota, pterosaurs, feathered and non-feathered dinosaurs, amphibians, fish, lizards and of course primitive birds. The authors of a new study, which confirm the Midddle Jurassic age of the Daohugou Beds have documented at least thirty different vertebrate taxa to date, including two lizards, a tadpole from a frog, five dinosaurs, four early mammals and thirteen pterosaurs.

No Birds Found

Intriguingly, no birds, however, this may not be so much of a surprise as birds may not have evolved at the time of deposition of the first fossil assemblage. What is known for certain is that a number of the dinosaur species identified to date from the Daohugou Beds are very similar to birds, Anchiornis for example, was extremely bird-like.

To read an article on the discovery of Anchiornis: Older than Archaeopteryx – Dinosaurs on their Way to Becoming Birds.

At an estimated 160 million years old, the Daohugou Beds are older than all the major bird-bearing fossil strata known, no definitive bird fossil may have been identified to date, but that is not surprising as at the time of the separation of the Aves from the Dinosauria, the birds closest relatives those non-avian Theropods, are going to look very similar. What can be inferred from the evidence is that the ecosystem preserved as the Daohugou Biota represents the closest known to that point in geological time when the birds and the Dinosauria effectively split.

The Daohugou Biota

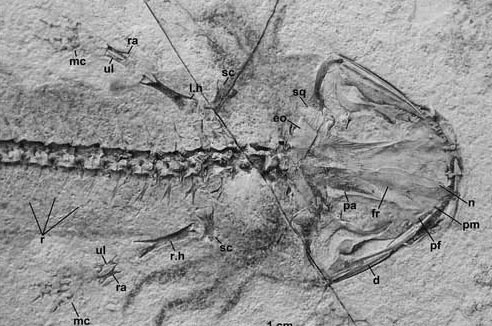

The Daohugou Biota is named after a small Chinese village close by to one of these six fossil locations. What the international team of researchers have done is to link these locations together to prove that they represent a sequence of strata that was laid down at roughly the same point in deep time. Radiometric dating has identified the age of the strata, but it is the presence of a signature fossil that has enabled the scientists to correlate the age of the separated deposits based on the fossils they contain. The presence of the fossilised remains of a salamander (Chunerpeton tianyiensis) links these six locations together. This amphibian’s fossils have effectively become a zonal fossil tying these six deposits together.

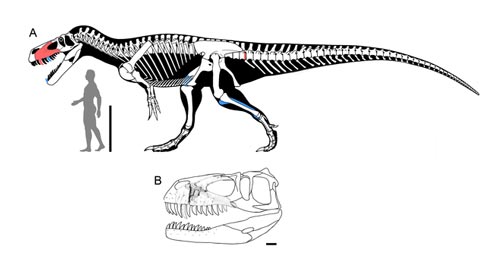

North-eastern China in the Middle Jurassic – Daohugou Biota

A rich and diverse Jurassic environment dominated by small mammals, pterosaurs and feathered theropods.

Picture credit: Julia Molnar

Biostratigraphy

The method of using the fossils of one or more species to identify the relative age of rock strata is called biostratigraphy. C. tianyiensis has become a zonal fossil, a role more often than not played by invertebrates such as ammonites, graptolites and crinoids.

More importantly, although there are a number of families of vertebrates common to both the Daohugou Biota and the younger Jehol Biota, these two formations together represent an different ecosystems millions of years apart. The Daohugou Biota and the Jehol Biota are separate Lagerstätte assemblages that between them provide scientists with an unparalleled window into life in the Middle Jurassic and the Early Cretaceous of north-eastern China.

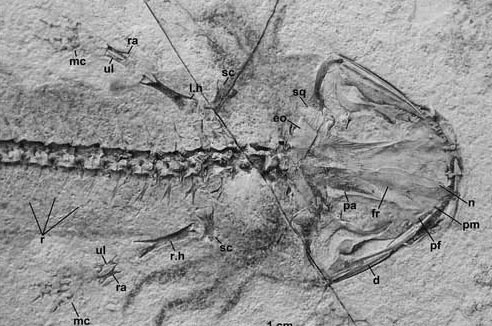

The Preserved Forequarters of a Specimen of C. tianyiensis (A Salamander)

Even the fine gills have been preserved.

Picture credit: Chinese Academy of Sciences/Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology

Dating the Lioaning and Hebei Sediments

A spokes person from Everything Dinosaur commented:

“There has been confusion over the dating of the Lioaning and Hebei sediments, caused in part due to the large amount of fossil material that was made available to study which came from dubious sources such as local fossil collectors and dealers who rarely revealed exactly where the specimens came from, but now it seems that we have two “lost worlds” to study, one representing the Middle Jurassic and one representing younger sediments dating from the Cretaceous. It is very likely that the Daohugou Beds will prove to be at least as biologically diverse as the fossil material that makes up the Jehol Biota, so we can expect to hear more announcements soon about further vertebrate discoveries.”

The Middle Jurassic deposits from these six Chinese locations have already provided fascinating glimpses into the weird and wonderful animals that lived in the forests and lakes that covered this part of the world 160 million years ago. For instance, in 2008, Everything Dinosaur reported on the discovery of the bizarre fanged, feathered little dinosaur called Epidexipteryx.

Epidexipteryx

It has been suggested that this little dinosaur, which was no more than thirty centimetres in length, may have climbed trees. For fans of the Pterosauria, the Daohugou Beds have provided a whole array of basal and derived forms of flying reptile such as the anurognathid pterosaur called Jeholopterus ningchenensis (note the confusing name from Jehol, although according to this new scientific paper, this pterosaur belongs to the Daohugou Biota and not the later Jehol Biota).

A number of rhamphorhynchid pterosaurs have been identified and sharing the same Jurassic skies was the recently discovered member of the Wukongopteridae pterosaur family called Darwinopterus modularis.

Composite Image of the Main Slab and Counter Slab of the Holotype Material of J. ningchenensis

Pterosaur fossil material.

Picture credit: Chinese Academy of Sciences/Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology

To read more about the discovery of the flying reptile called Darwinopterus: New Transitional Pterosaur Fossil Discovery from North-eastern China.

Shedding Light on the Evolution of Mammals

These sediments are also shedding light on the evolution of mammals and what bizarre forms there were in the Middle Jurassic. Fossils of a tree climbing mammal with a membrane of skin stretched between its limbs have been found. It has been suggested that this creature, called Volaticotherium, occupied the same niche in the arboreal ecosystem as today’s flying squirrel from Asia. Living alongside the abundant salamanders was the peculiar Castorocauda, a mammal adapted to an aquatic lifestyle with a broad, flattened tail to help it swim.

These creatures may seem strange to us, but we suspect that lurking in the finely-grained sediments of the Daohugou Beds even more bizarre vertebrates are awaiting discovery.

To view replicas and models of prehistoric animals from the Daohugou Biota: PNSO Age of Dinosaurs Models.