Chinese Scientists Study Hipparion Skull

Scientists from China’s Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology (IVPP) have discovered a skull fossil of a Hipparion, a three-toed horse with a long nose that lived approximately 5 million years ago (Pliocene Epoch). The very well preserved fossil skull was found in the north-western province of Gansu, at a location where many Pliocene aged mammal fossils have been discovered in recent years.

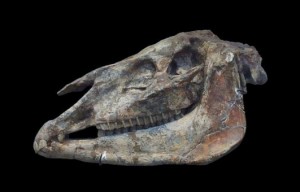

Prehistoric Horse Skull

The fossil, is the most intact and complete Hipparion skull found in China so far, it was unearthed in the city of Linxia a few weeks ago (late January), but it has taken a while to clean and prepare to permit the scientists from the Chinese Academy of Scientists (IVPP) to study it properly.

Deng Tao, a researcher with the IVPP commented that:

“The discovery provided vital clues for the study of structural features of the species, especially for the research of the “nasal notch”.”

The Hipparion Skull found in China

Picture credit: Chinese Academy of Sciences (IVPP)

Hipparion

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur, stated that the Hipparion was a genus of prehistoric horse that evolved in the Miocene and survived right up until the Pleistocene Epoch. Many species have been ascribed since this genus was first named back in the 1830’s. This plains dweller thrived in the drier conditions of the Miocene which aided the spread of grasslands – fossils of horses ascribed to this genus have been found in Europe, Asia, North America and China.

Originating in North America, the Hipparion is believed to have spread to the Old World over the Bering land bridge, which used to connect present-day Alaska and eastern Siberia. The five-million-year-old skull will help scientists to understand a little more about how the horses nasal passages became elongated. The evolution of the relatively long front end of the horse’s skull is believed to be an adaptation to living on open grasslands where fast running to avoid predation became a necessity and the extended nasal openings may have made breathing more efficient.

The publishing of this new discovery coincides with the release of another study into prehistoric horses that postulates that mammals get smaller as world temperatures rise. Researchers at the Florida Museum of Natural History (Florida University), have been studying the teeth of one of the first types of horses to evolve a genus known as Sifrhippus, a type of horse that lived 56 million years ago in North America at a time when the Earth’s average temperature was much higher than it is today.

In a relatively short period, geologically speaking, a rapid increase in carbon dioxide levels in Earth’s atmosphere and oceans sent global temperatures shooting upwards by about 5.5 degrees Celsius over a period of between 10,000-20,000 years. Global temperatures rose to approximately 28 degrees Celsius – turning Earth into a “hot house” with rain forests covering many northern latitudes.

Looking at thousands of years-worth of preserved fossils that Sifrhippus left behind in the Bighorn Basin of Wyoming, researchers found that the horse shrunk 30 per cent over 130,000 years, from 5.4 kilogrammes to 3.8 kilogrammes on average. The study that analysed the size of fossil teeth from these ancient, but tiny horses showed that during a period of cooling that followed in the next 45,000 years, this miniature “Mr Ed” grew to be about 6.8kg.

Researcher Jonathan Bloch (University of Florida) commented

“What’s surprising is that after they first appeared, they then became even smaller and then dramatically increased in size, and that exactly corresponds to the global warming event, followed by cooling.”

The scientists conclude that this evidence suggests that miniaturisation in mammals may occur as global temperatures increase. With the current trend towards a warmer planet, this may lead to the evolution of miniature mammal species (perhaps even a mini H. sapiens) in the future.

What is unclear at this stage, is whether or not the fossil teeth of Sifrhippus or the skull of the Hipparion found in China are able to help explain how “Mr Ed” the horse from the 1950s television series was able to talk.

For replicas and models of prehistoric mammals: Safari Ltd. Prehistoric Mammal Models.

Leave A Comment