In a Flap over Pterosaur Anatomy that enabled them to Fly

A team of US/UK based researchers have published a paper outlining their findings on how the flying reptiles (pterosaurs) were able to take to the air and fly so efficiently.

In a new study published in the online palaeontological journal “PLoS ONE”, the joint Anglo/American research team state that the hollow bones of pterosaurs, coupled with large air sacs inside their bodies, reduced the density of the animals and helped them to take to the skies. The team’s study indicates that pterosaurs had a very efficient breathing system, similar in structure to modern birds and it was this system in conjunction with the light skeletons that enabled these flying reptiles to have an aerial lifestyle.

Pterosaurs are not Dinosaurs

Pterosaurs are not dinosaurs, but flying archosaurs, closely related to Dinosauria. The earliest pterosaur fossils date from the Triassic, although their exact evolutionary path is unclear due to the limited amount of fossils found so far. A pterosaur’s wings were made of a large membrane of skin that stretched from the end of an extremely long fourth finger to its body and back legs. The wing membrane was strengthened with stiffening fibres (actinofibrillae), tests on models show that they were efficient fliers not simply gliders.

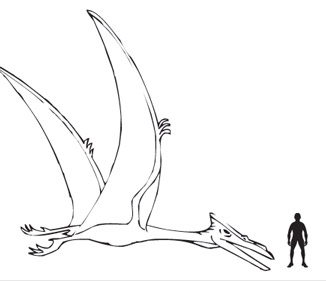

The first pterosaurs such as the anurognathids were small, some no bigger than a blackbird. They had shortened wrist bones, blunt snouts and other features indicative of a primitive pterosaur group. Later forms such as the Late Cretaceous azhdarchids, such as Quetzalcoatlus were much more advanced. Some of the azhdarchid pterosaurs grew into giants. Quetzalcoatlus, one of the largest pterosaurs known to date had a wingspan in excess of 11 metres. These pterosaurs has long, toothless beaks, long necks and immense wingspans. Many scientists believe that this type of flying reptile soared and glided using air currents and hot thermals.

A Scale Drawing of the Giant Azhdarchid Quetzalcoatlus

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Stalking Predators

Recently, a new theory about the lifestyle of these huge reptiles was put forward by a team of English researchers. These animals may have had more of a terrestrial existence than previously thought. Fossils of many large pterosaurs are associated with marine sediments, indicating that they lived in coastal areas. Air currents hitting cliffs and rising up and the onshore breezes would have assisted these large animals in their bid to get airborne. However, fossils of Quetzalcoatlus (Quetzalcoatlus northropi) are associated with non-marine sediments. It has been suggested that these huge animals were mainly ground dwellers, stalking the Cretaceous plains, flushing out prey and snapping them up with their long beaks.

An Alternative View of Azhdarchid Pterosaurs

Picture credit: Mark Witton

To read more about this viewpoint: Getting Stalked by a Flock of Quetzalcoatlus.

One of the problems scientists have with the larger Pterosaurs is that their fossils are extremely rare, their delicate pneumatised bones (filled with air), were light and strong but not as robust as even the bones of smaller theropods (which also had pneumatised bones), therefore not able to survive the preservation process. A number of theories have been put forward as to the lifestyles of the largest pterosaurs, everything from vultures to giant herons. The azhdarchids were some of the very last pterosaurs to evolve and lived at the very end of the Cretaceous (Campanian and Maastrichtian faunal stages). By this time in the Earth’s history most of the other types of flying reptiles were extinct, replaced by another type of animal more suited to life in the air – Aves (the birds).

To view a model of a Quetzalcoatlus and other pterosaur figures and replicas: Dinosaur, Pterosaur and Prehistoric Animal Models.

Growing to the size of a small aircraft in some cases, the American and British research team were puzzled as to how these large reptiles were able to soar in the air.

Pterosaurs

According to this new study, the pterosaurs were equipped with balloon-like air sacs that extended from the lungs throughout the body and in conjunction with their hollow bones, this provided these flying reptiles with a super efficient breathing system. The less dense bones would also have helped reduce weight helping them in their bid to become aerial.

A couple of years ago, a team of scientists at the University of Manchester, England, published research into dinosaur breathing systems and concluded that many types of dinosaur (especially saurischian dinosaurs), were equipped with a very efficient bird-like breathing system.

To view this article: Insight into Dinosaur Respiration – A Breathe of Fresh Air.

Birds have a much more efficient breathing system than mammals. This new paper suggests that the pterosaurs also possessed an advanced and efficient respiration system, better than our own for example.

Instead of just one entrance/exit point in the lungs they have openings at both ends, plus the addition of a series of balloon-like air sacs in front and behind the lungs. It is these air sacs, not the lungs that inflate and deflate with each breathe. Acting like a set of bellows they pump air through the lungs and out of a different tube than it went in. This one-way system, with old expired air never mixing with fresh air, rich in oxygen to power muscles is a very efficient system. Like birds, the pterosaurs may have had large hearts to help provide the power required to make this breathing system operate, but unfortunately, soft tissues such as internal organs are extremely rare in the fossil record and none of the team members at Everything Dinosaur can remember reading a research paper on fossilised pterosaur hearts.

Commentating on the research, Dr David Unwin, a palaeobiologist in the Dept. of Museum Studies at the University of Leicester, a co-author of the study stated:

“We have identified the breathing system of a pterosaur. It’s a surprisingly efficient mechanism with the same essential structure of a modern bird’s lung apparatus — except 70 million years earlier”.

The research project began to take shape following a visit to Berlin by Assistant Professor Leon Claessens from the College of the Holy Cross in the United States and Assistant Professor Patrick O’Connor from Ohio University. The Americans studied the well-preserved rib cage of a pterosaur, the same fossil had been examined by Dr Unwin a few years earlier. The fossil showed that the rib cage was mobile and that it could articulate with the sternum or breast plate. Projections on the topmost ribs provided important leverage for the muscles that allowed the rib cage to move, expanding and contracting – a prerequisite for a bird-like respiration system.

The three scientists then decided to work together to find out how these flying reptiles were able to achieve sustained, powered flight.

Studying Pterosaur Body Fossils

As well as studying a number of pterosaur body fossils, the researchers also compared the anatomy and structure of pterosaurs with modern bird skeletons. Medical CT scans and X-rays were used to get a better impression of the internal structure of the bones.

In a statement, the researchers commented:

‘The air sacs extend all the way to the tips of the wings which opens up a wide range of possibilities for the use of air sacs during flight and for social behaviours. We found a direct relationship between the proportion of the skeleton invaded by air sacs and the absolute body size of an animal”.

Smaller flying animals have fewer pneumatised bones. They have a lower mass and so require less energy to get and remain airborne. Large flying animals such as pterosaurs have many more pneumatised bones, giving them less bone density and making it easier for them to sustain flight.

Studies of the skulls and endocasts of pterosaur brains indicate that they had a very good sense of balance and keen eyesight, all very helpful if you are going to fill an environmental niche based on flying. As a group, the pterosaurs rapidly diversified during the Triassic and Jurassic before, towards the end of the Mesozoic, encountering competition from the new types of flying creature – the birds.

The last of the pterosaurs went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous, approximately 66 million years ago.

Leave A Comment