New Rhamphorhynchus Study Highlights Ontogenetic Niche Partitioning

Scientists have described in detail a Rhamphorhynchus fossil from the famous Solnhofen deposits of Germany. Most Solnhofen pterosaur fossils are pancaked, but specimen number NHMUK PV OR 37002 has been preserved in three dimensions. This has permitted the researchers to assess how Rhamphorhynchus changed as it grew. The fossil represents an extremely large individual. It had an estimated wingspan of approximately 1.8 metres. When this fossil was studied over a hundred years ago, it was thought to represent a new species. It was named Rhamphorhynchus longiceps (Woodward, 1902). However, the fossil material is now thought to represent an extremely mature Rhamphorhynchus muensteri.

The Largest Rhamphorhynchus Known to Science

The fossil material represents the largest known specimen of Rhamphorhynchus. It is exceptionally important due to the completeness of the specimen and its excellent state of preservation. In addition, as it represents the remains of a large, mature adult it can help palaeontologists to gain a better understanding of the growth of non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs, especially at upper sizes.

Furthermore, the specimen exhibits unusually flattened teeth. This suggests a change in diet for these flying reptiles as they matured.

Specimen NHMUK PV OR 37002 represents an exceptionally large and mature adult Rhamphorhynchus muensteri from the Eichstätt locality of Solnhofen. Counterplates and separate plate containing caudal series attached to the main plate are outlined in red. cdv, caudal vertebrae on separate plate and counterplate attached to main plate; hu, humerus; lwpx1, left wing phalanx 1; lwpx2, left wing phalanx 2; lwpx3, left wing phalanx 3 on counterplate; lwpx4, left wing phalanx 4 on counterplate; olwpx2, outline of left wing phalanx 2 on counterplate; olwpx3, outline of left wing phalanx 3; olwpx4, outline of left wing phalanx 4; orwpx3, outline of right wing phalanx 3; orwpx4, outline of right wing phalanx 4; orpes, outline of right pes; rad/uln, radius and ulna; rpes, right pes on counterplate; rwpx2, right wing phalanx 2; rwpx4, right wing phalanx 4 on counterplate. Note scale is 5 cm. Picture credit: Hone and McDavid.

Picture credit: Hone and McDavid.

Studying the Rhamphorhynchus muensteri Specimen

Rhamphorhynchus is one of the most extensively studied pterosaurs. There are over a hundred specimens in museum collections. Most of these were sourced from the remarkable Solnhofen deposits in the German state of Bavaria. The vast majority of these specimens represent juveniles and even those fossils thought to represent adults typically have a wingspan of no more than a metre. NHMUK PV OR 37002 represents a giant rhamphorhynchine. It is also amongst the largest non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs known, and certainly the most complete specimen of an animal in excess of 1.5 m in wingspan. This Rhamphorhynchus fossil helps support the theory that some pterosaur taxa in the Jurassic were capable of reaching large sizes.

Moreover, this specimen displays anatomical differences not observed in smaller individuals, providing insights into the late-stage development of this genus.

Size comparison of different Rhamphorhynchus muensteri specimens: (anti-clockwise from top left) A – the smallest known BMMS A3 (21 mm skull length), a generalised ‘typical adult’ specimen C (122 mm skull length), D the second largest known GPIT RE/7321 (150 mm skull length) and B, the largest known NHMUK PV OR 37002 (201 mm skull length). Note scale is 1 metre. Picture credit: Hone and McDavid.

Picture credit: Hone and McDavid.

Ontogenetic Niche Partitioning

The study has been published in the open-access journal “PeerJ”. The researchers identified several changes in the anatomy of Rhamphorhynchus as it grew and matured. For example, analysis of the skull demonstrated a significant reduction in the size of the eye socket and an increase in the size of the temporal fenestra. In addition, it was noted that NHMUK PV OR 37002 had flattened teeth, very different from the needle-like teeth found in juveniles.

Skulls of specimens of Rhamphorhynchus muensteri at different sizes. Top to bottom: (A) BSPG 1889 XI 1 (‘Exemplar 7’, skull length 35 mm per Wellnhofer, 1975), scale bar 25 mm; (B) YPM VP 1778 (‘Exemplar 33’ of Wellnhofer, skull length 90 mm, measured by SNM using ImageJ), scale bar 35 mm; (C) GPIT RE/7321 (‘Exemplar 81’, skull length 150 mm per Wellnhofer, 1975, illustration mirrored and partially adapted from Wellnhofer, 1975), scale bar 50 mm; (D) NHMUK PV OR 37002, skull length 201 mm. Picture credit: Hone and McDavid.

Picture credit: Hone and McDavid.

These characteristics illustrate a developmental transition from smaller to larger Rhamphorhynchus specimens and align with similar traits found in other large rhamphorhynchines, indicating a consistent pattern in their growth.

This would also then point to ontogenetic niche partitioning with adults and juveniles targeting different prey items. Ontogenetic niche partitioning refers to the process by which individuals of the same species or closely related species exploit different resources or habitats at different stages of their development (ontogeny). The authors of the paper propose a dietary shift for Rhamphorhynchus as it grew and matured. Rhamphorhynchus juveniles may have been mostly insectivorous. As these pterosaurs grew, they become piscivorous. The largest individuals may have shifted to other prey, or to different prey types.

Are Modern Gulls an Analogue?

Rhamphorhynchines may have moved inland as they grew and matured. Whilst still tied to water bodies, they may have become more generalist feeders. A modern-day analogue could be gulls (Laridae). Many types of gull prefer marine or at least aquatic systems but are capable of foraging successfully in more terrestrial systems. If the biggest rhamphorhynchines lived inland, this might explain their absence from the fossil record. All things being equal, a pterosaur in a marine environment probably has a great fossil preservation potential than for example, a flying reptile that lived on an inland plain.

Skull of Rhamphorhynchus muensteri NHMUK PV OR 37002 in near lateral view showing the 3D nature of the specimen (A) and restoration of the cranium and mandible in right lateral view (B). Preserved bone and teeth are in white, obscured or reconstructed portions are in grey. Note the skull has no visible sutures indicating a fully mature, adult animal. Scale is 5 cm. Picture credit: Hone and McDavid and University College London.

Large Non-pterodactyloid Pterosaurs of the Jurassic

With a wingspan estimated at around 1.8 metres, the pterosaur fossil at the centre of this new research represents one of the largest non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs of the Jurassic. Pterodactyloids are thought to have evolved in the Jurassic and this suborder includes the biggest flying vertebrates of all time. For example, the Azhdarchidae, the Ornithocheiridae and Late Cretaceous giants such as Pteranodon longiceps.

In the summer of 2024, we wrote an article about a pterosaur humerus found in Oxfordshire that suggested a Jurassic pterodactyloid with a wingspan in excess of three metres.

To read this article: A Giant Oxfordshire Pterosaur.

Rhamphorhynchus is a member of a more basal group of pterosaurs, although the phylogeny of the Pterosauria remains controversial. Although, non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs did not reach the enormous size of some later pterosaurs, there is some evidence to indicate that some taxa may have had a wingspan in excess of one and a half metres. For example, when the rhamphorhynchid Dearc sgiathanach was described in 2022 (Jagielska et al), its wingspan was thought to be greater than two metres. However, the size of D. sgiathanach remains uncertain.

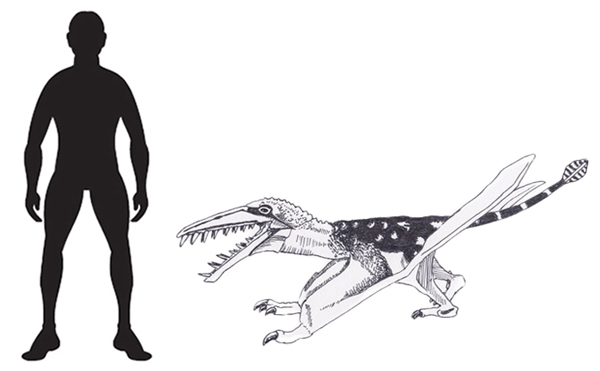

A scale drawing of the large Jurassic pterosaur Dearc sgiathanach commissioned by Everything Dinosaur for a Dearc fact sheet. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The image above shows a scale drawing of the Middle Jurassic rhamphorhynchine Dearc sgiathanach, although the size of this pterosaur remains uncertain. The drawing was commissioned for a fact sheet that accompanied sales of the CollectA Deluxe Dearc figure.

To view the range of CollectA Deluxe prehistoric animal models: CollectA Deluxe Prehistoric Life Models.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of Dr David Hone (Queen Mary University of London) in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “A giant specimen of Rhamphorhynchus muensteri and comments on the ontogeny of rhamphorhynchines” by David W. E. Hone and Skye N. McDavid published in PeerJ.