New Research Solves the Mystery of the Pterosaur Tail

A newly published scientific paper outlining the latest Rhamphorhynchus research has solved a mystery about pterosaur flight. Pterosaurs were the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight. Thanks to this new study, an evolutionary puzzle relating to how pterosaurs flew has been solved. Controlled powered flight was achieved with the aid of a lattice-like vane on the tip of the tail of many types of early flying reptile. The diamond-shaped vane consisted of interwoven membranes. This prevented their long tails fluttering like flags in the wind. These structures helped to stabilise these creatures in flight and may have aided steering.

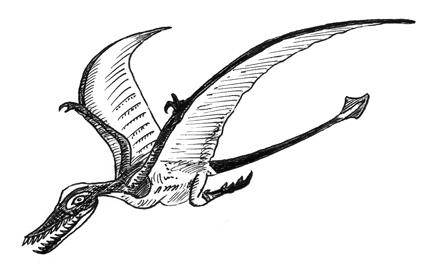

A rhamphorhynchine pterosaur illustration. The diamond-shaped tail vane was made from interwoven membranes, and this played a key role in flight stability. Picture credit: Natalia Jagielska.

Picture credit: Natalia Jagielska

Previous research revealed that maintaining stiffness in the tail vane was crucial to enable early pterosaur’s flight. How exactly this was achieved remained unknown. However, this new research, published in eLife, has provided fresh data on pterosaur anatomy. This in turn, permitted this puzzle about the flight of pterosaurs to be resolved.

The study was led by palaeontologists from the University of Edinburgh. The researchers discovered that the tail vane probably behaved like a sail on a ship. It became tense as the wind blew through the cross-linked membranes thus allowing these reptiles to steer themselves through the sky.

An illustration of a pterosaur. Note the diamond-shaped tail vane. Rhamphorhynchus research has solved a mystery about pterosaur flight. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Rhamphorhynchus Research

The hollow bones of pterosaurs have poor fossil preservation potential. However, thanks to the remarkable fossils from famous Lagerstätten such as the pterosaur material from Solnhofen in Germany, scientists have numerous, early non-pterodactyloid specimens to study. Many of the most complete and best-preserved specimens represent Rhamphorhynchus muensteri. Some of these fossils are preserved in three-dimensions and also include traces of soft tissue such as skin and flight membranes.

Recently, Everything Dinosaur reported upon the study of a giant Rhamphorhynchus: Rhamphorhynchus and Ontogenetic Niche Partitioning.

The scientists used a sophisticated research technique called Laser Simulated Fluorescence (LSF). Exposing fossils to this intense light causes organic tissues almost invisible to the naked eye to glow. The researchers were able to observe the delicate internal structures of the Rhamphorhynchus tail vane. This provided the team with fresh insights into pterosaur anatomy and evolution.

The image (above) shows a replica of Rhamphorhynchus. This pterosaur model is part of the Wild Safari Prehistoric World model range.

To view this range of prehistoric animal figures: Wild Safari Prehistoric World Figures.

Universities Collaborating with Museums

The research involved scientists from the University of Edinburgh and the Chinese University of Hong Kong in collaboration with the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh and the London Natural History Museum. It was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

Lead author of the study Dr Natalia Jagielska a PhD graduate from the University of Edinburgh stated:

“It never ceases to astound me that, despite the passing of hundreds of millions of years, we can put skin on the bone of animals we will never see in our lifetimes.”

Thinking of a practical implication for this research, Dr Jagielska added:

“Pterosaurs were wholly unique animals with no modern equivalents, with a huge elastic membrane stretching from their ankle to the tip of the hyper-elongated fourth finger. For all we know, figuring out how pterosaur membranes worked, may inspire new aircraft technologies.”

This newly published research provides a fascinating glimpse into early pterosaur evolution. The tail vane was a critical structure that helped these amazing creatures dominate the skies. However, later pterosaurs had much reduced tails and lost their tail vanes. This opens up new lines of enquiry into the evolution of the Pterosauria.

Dr Nick Fraser, (Keeper of Natural Sciences, National Museums Scotland), said:

“Without the researchers’ vision to apply new technology to apparently well-understood fossils, this tail vane would have remained in the dark. It is exciting to now see a critical feature of the pterosaur’s anatomy so beautifully displayed.”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Edinburgh in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “New soft tissue data of pterosaur tail vane reveals sophisticated, dynamic tensioning usage and expands its evolutionary origins” by Natalia Jagielska, Thomas G Kaye, Michael B Habib, Tatsuya Hirasawa and Michael Pittman published in eLife.

Visit the award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Pterosaur Models and Toys.