The famous marine sediments of the Chesapeake Group, which outcrops across North Carolina, Delaware, Virginia and Maryland in the USA are regarded as some of the most extensively studied Cenozoic marine deposits in the world. The first fossil described from North America (Ecphora quadricostata) a marine snail which was scientifically described in 1685, comes from deposits associated with the Chesapeake Group (St Marys Formation)

A Miocene Fish Fossil

Many different types of fish and marine invertebrates have been named from fossils found at locations such as the Calvert Cliffs on the western shore of Chesapeake Bay (Maryland). Cetacean fossil material is also associated with these strata, along with sea cows and many seabirds such as gannets and fulmars. Marine turtles and the remains of land tortoises and freshwater crocodiles are also known.

A researcher from the Calvert Marine Museum (Maryland), is one of the authors of a recently published scientific paper that highlights a first for these Miocene-aged deposits. The partial skull of a fish has been found crammed full of tiny, fossil poo probably created by scavenging worms that once feasted on the head of the fish.

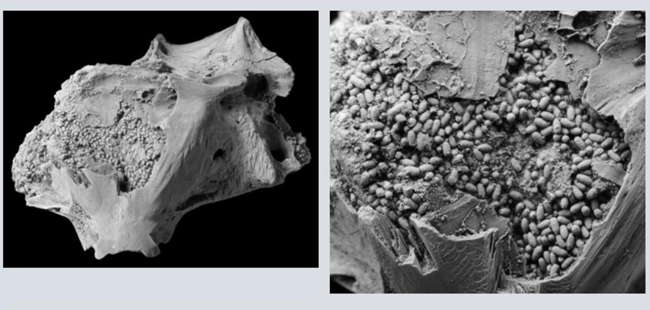

Photograph (left) of the partial skull of the Miocene Stargazer fish (ventral view). Some of the bone has broken away revealing hundreds of fossilised faecal pellets filling the braincase. A close-up view of the faecal matter (right). Picture credit: Calvert Marine Museum.

Picture credit: Calvert Marine Museum

Stargazer Skull (Astroscopus spp.)

The specimen represents the first skull completely infilled with faecal pellets ever recorded, the fossil poo (micro-coprolite) is an example of the coprulid ichnospecies Coprulus oblongus. The pellets range in size from 1 mm to 5 mm in length and the skull comes from a Stargazer fish (Astroscopus), a genus of bottom living fish that bury themselves in soft sediment lying in wait to ambush small fish and invertebrates that come within striking distance.

A fossil of worm faecal pellets from Miocene-aged deposits from southern Maryland (USA). Each pellet is approximately 3 millimetres in length. Picture credit: Calvert Marine Museum.

Picture credit: Calvert Marine Museum

Crocodile Coprolites Studied Too

Writing in the academic journal “Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia”, the researchers also describe a series of trace fossils found in preserved crocodile coprolite from the Miocene Calvert Formation. The fossil crocodile poo was tunnelled into, presumably evidence of the faeces being consumed (coprophagy). The scientists are unable to identify the organism(s) responsible for producing the burrows although the sides of the burrows preserve evidence of scratches which are thought to be feeding traces.

Crocodile coprolite broken open showing trace fossil burrows made by a coprophagus organism. Feeding gouge marks can be seen on the walls of the burrow. Length of crocodile coprolite 17.5 cm approximately. Picture credit: Calvert Marine Museum.

Picture credit: Calvert Marine Museum

Whilst these remarkable fossils might not be as awe-inspiring as the whale bones that have been found in these rocks, they provide important evidence with regards to the recycling of nutrients from faecal matter in Miocene-aged marine environments.

The scientific paper: “Coprolites from the Calvert Cliffs: Miocene fecal pellets and burrowed crocodilian droppings from the Chesapeake Group of Maryland, USA” by Stephen J. Godfrey, Alberto Collareta and John R. Nance published in Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia.

Leave A Comment