Re-drawing the “False Sabre-tooths” with New Research

Paul Barrett of the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Oregon, has put the prehistoric “cats” amongst the prehistoric pigeons with the publishing of a new scientific paper that reassesses the evolution of the “false-sabre tooths”, the Nimravidae. Previous studies had focused on the remarkable, over-sized canines of these placental predators. The paper, published in the journal “Scientific Research”, examined non-sabre-tooth anatomical features and as a result, a different hypothesis on the evolution of nimravids has been proposed.

An Over Emphasis on the Teeth and Skulls

Previous studies attempting to map the evolutionary history of the Nimravidae from their origins in the Middle Eocene Epoch to their extinction in the Late Miocene, had focused on examining the shape of the skull and the dentition (teeth). This over reliance on anatomical characters associated with the teeth and the necessary cranial adaptations to wield the enlarged canines led to palaeontologists thinking that these predators evolved in a relatively narrow, restricted way – that there was a gradual evolution of more specialised sabre-tooth features.

This new research based on sophisticated Bayesian analysis looking at a much broader suite of characters and traits suggests that the Nimravidae split, relatively early on in their evolution, into two distinct clusters. One branch (Hopliphoninae) became sabre-toothed hunters, whilst the second branch (Nimravinae) evolved traits reminiscent of extant big cats.

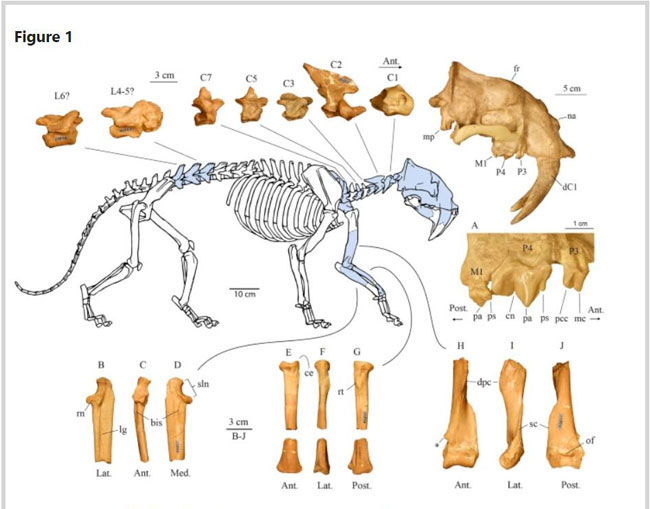

Eusmilus adelos

In addition to the reassessment of the evolutionary direction of the nimravids, PhD student Paul also examined the fossilised remains of a lion-sized specimen found in Wyoming (White River Formation). This has led to the erection of a new species Eusmilus adelos. Regarded as the biggest member of the Hopliphoninae described to date, it is suggested that a large predator such as E. adelos specialised in hunting prey bigger than itself. Eusmilus adelos may have tackled tapirs, rhinoceratids and large anthracotheriids (an extinct family of hooved, even-toed ungulates distantly related to hippos).

Studying False Sabre-tooths

Coeval hoplophonines were smaller and the author suggests these predators specialised in tackling much smaller prey. This niche partitioning (avoiding of competition by focusing on different resources), would have reflected what is seen on the plains of Africa today amongst extant felids. Large predators such as lions specialising in prey bigger than themselves, whilst smaller felids such as the caracal (Caracal caracal) and the leopard (Panthera pardus) tend to hunt prey smaller than themselves.

To read a related article from Everything Dinosaur that focuses on a study into the evolution of sabre-toothed predators across deep geological time, that suggests that these superficially similar animals evolved very different hunting strategies: Sabre-toothed Predators Evolved Different Hunting Styles.

The scientific paper: “The largest hoplophonine and a complex new hypothesis of nimravid evolution” by Paul Zachary Barrett published in Scientific Reports.