Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch – Pangaea Split Later Than Thought

A fossilised skull of a stem mammal dating back to the Lower Cretaceous suggests that the super-continent Pangaea split up more recently than previously thought. The skull, identified as a new species, comes from Utah and it indicates that there were still land links between North America and other landmasses making up Pangaea, as this is the first evidence of a member of the Hahnodontidae to have been described from North American fossil material.

Linking Super-continents Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch

Picture credit: Jorge A. Gonzalez

Scientists, including researchers from the University of Chicago and the Utah Geological Survey writing in the journal “Nature”, have named the new stem mammal Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch.

Lead author of the study Zhe-Xi Luo (University of Chicago), explained that palaeontologists had thought that the primitive precursors to today’s mammals – the monotremes, marsupials and placental mammals, were anatomically similar and ecological generalists. However, recent fossil discoveries suggest that many stem mammals were very specialised.

Zhe-Xi Luo stated:

“Now we know mammal precursors developed capacities to climb trees, to glide, to burrow into the ground for subterranean life, and to swim. With this new study, we also know that they dispersed across from Asia and Europe, into North America, and farther onto major southern continents.”

Honouring Richard Cifelli

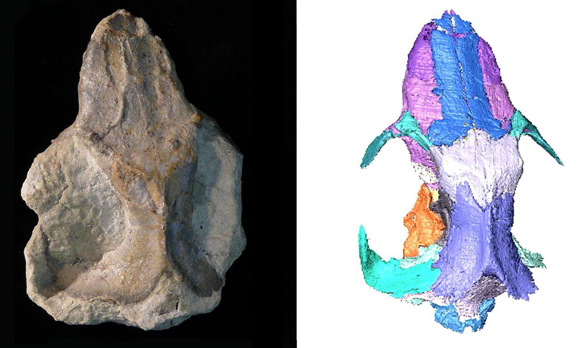

The genus name honours American palaeontologist Richard Cifelli, at Oklahoma University. Professor Cifelli is regarded as one of America’s leading experts in North American Cretaceous mammals. The species name “wahkarmoosuch”, means “Yellow Cat” in the local native American language for that part of Utah. The fossil comes from the Yellow Cat Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation. Sophisticated high-resolution computerised tomography (CT), was used to create a detailed, three-dimensional model of the skull.

James Kirkland, co-author of the paper and a Utah State palaeontologist commented:

“The skull of Cifelliodon is an extremely rare find in a vast fossil-bearing region of the Western Interior, where the more than 150 species of mammals and reptile-like mammal precursors are represented mostly by isolated teeth and jaws.”

The Fossilised Skull of C. wahkarmoosuch and a Computer -generated Image of the Fossil Material

Picture credit: Huttenlocker et al

Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch – A Nocturnal Predator

Cifelliodon wahkarmoosuch was small, weighing around two kilograms, it was probably about the size of a terrier. This might be tiny compared to some extant North American mammals around today such as the moose, wolf and bison, but back in the Early Cretaceous, some 130 million years ago, it was a relative giant amongst its Cretaceous contemporaries. Analysis of the teeth and preserved teeth sockets suggest that it had teeth were similar to fruit-eating bats and it could bite, shear and crush. It may have been omnivorous, eating small animals but also incorporating plants into its diet.

The skull reveals that this newly described species had a relatively small brain and giant olfactory bulbs to process smell. The small orbits (eye-sockets), suggest that C. wahkarmoosuch probably relied on its sense of smell to find food. It probably did not have good eyesight or colour vision and Cifelliodon may have been nocturnal.

Super-Continent and Land Bridges

The research team have assigned Cifelliodon to the clade Haramiyida, a group of mammaliaform cynodonts that have a long temporal range in the fossil record. Most of these animals are known from fragments of jawbone or fossil teeth. The teeth, which are by far the most common fossil remains of these animals, resemble those of another ancient type of mammal the Multituberculata (Multituberculates). With the discovery of a North American Haramiyidan, scientists are going to have to re-examine fossil teeth from this area that had previously been assigned to the Multituberculata, these teeth might represent members of the Haramiyida.

The fossil discovery emphasises that Haramiyidans and some other vertebrate groups existed globally during the Jurassic-Cretaceous transition, meaning the corridors for migration via landmasses forming the super-continent Pangaea remained intact into the Early Cretaceous. There must have been land bridges permitting the migration of these small animals for longer than previously thought.

Haramiyidan Fossils

Most of the Jurassic and Cretaceous fossils of Haramiyidans are from the Triassic and Jurassic of Europe, Greenland and Asia. Hahnodontidae was previously known only from the Cretaceous of northern Africa. The Utah fossil discovery provides evidence of migration routes between the continents that are now separated in northern and southern hemispheres.

Commenting on the implications for the break-up of Pangaea, Adam Huttenlocker (University of Southern California), a co-author of the study said:

“But it’s not just this group of Haramiyidans. The connection we discovered mirrors others recognised as recently as this year based on similar Cretaceous dinosaur fossils found in Africa and Europe.”

The researchers conclude that hahnodontid mammaliaforms had a much wider, possibly Pangaean distribution during the Jurassic–Cretaceous transition.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the help of a press release from the University of Chicago in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Late-surviving Stem Mammal Links the Lowermost Cretaceous of North America and Gondwana” by Adam K. Huttenlocker, David M. Grossnickle, James I. Kirkland, Julia A. Schultz and Zhe-Xi Luo published in the journal Nature.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment