Watching the Birdie – Head for the Southern Hemisphere

Fossil Bird Challenges Perceptions About Avian Evolution

Researchers from the Swedish Museum of Natural History and the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath, have re-examined the fossilised remains of an ancient bird from Wyoming, which casts doubt on the generally held perception that the ancestor of all modern birds originated in the Southern Hemisphere. An examination of the avian fossil record has provided a fresh perspective. The fossil bird, named Foro panarium, was originally described and named back in 1992, but where this 52 million-year-old bird would perch on the avian family tree has been the subject of much debate.

Dr Daniel Field (Milner Centre for Evolution), in collaboration with Alison Hsiang (Swedish Museum of Natural History), have produced a scientific paper that supports the idea that this robust but poor flyer with relatively long legs from the famous Eocene-aged Green River Formation, is the earliest known example of a group of birds called Turacos or “banana eaters”.

Comparing the Skeleton of F. panarium to the Extant Ross’s Turaco (M. rossae)

Picture credit: BMC Evolutionary Biology

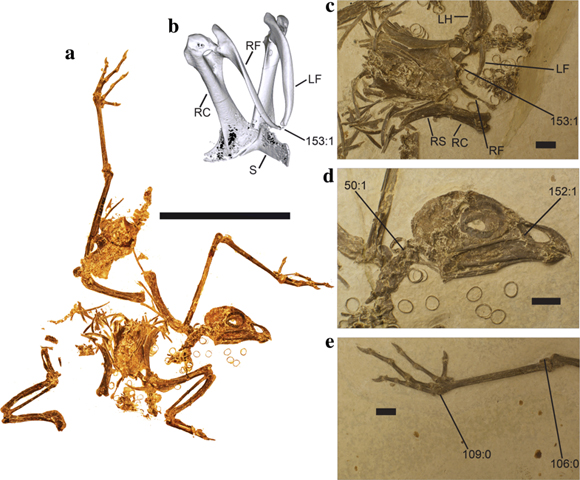

The picture (above) shows a stylised image of the holotype specimen of Foro panarium (a, c, d, e) compared to (b) 3-dimensional CT rendering of the pectoral region of Ross’s Turaco (Musophaga rossae). Note scale bar is 10 centimetres.

Birds – the Most Specious of all the Terrestrial Vertebrates

Some commentators might state that we are living in “the age of mammals”, it is true that many of the apex predators, large herbivores and hyper-carnivores around today are mammalian, but in terms of the number of species, there are more species of birds (estimated at 11,000), than there are species of mammals, or amphibians and reptiles for that matter. In addition, there are far more bird species in the Southern Hemisphere than in the Northern Hemisphere. Charles Darwin during his voyage on the Beagle, marvelled at the great diversity of bird species he encountered on his travels through South America, the Galapagos and islands of the Pacific Ocean.

Naturalists are very aware of the dramatically uneven global distribution of today’s Aves. Not only are species numbers higher south of the Equator, but many major groups of birds are entirely restricted to Africa, Australasia and South America which were all, once upon a time, part of the great southern super-continent of Gondwana.

Turaco Birds are Known for their Beautiful Plumage

Picture credit: Dr Daniel Field

Studying the Avian Fossil Record

Dr Field and Dr Hsiang set out to examine the avian fossil record to see if they could help to explain the uneven geographic distribution of modern-day birds. Did, as many scientists believe, the ancestor of all modern birds (Neornithes), originate in the Southern Hemisphere, or are there more complex issues in play restricting the distribution of birds through deep time?

In order to map the evolutionary history of our feathered friends – the avian dinosaurs, the scientists turned to the fossil record for answers. Writing in the academic journal “BMC Evolutionary Biology”, the scientists report their study of the 52-million-year-old fossil bird named Foro panarium. The taxonomic placement of this species has been controversial, as the fossil shows a mixture of anatomical characteristics. However, using updated information relating to other Eocene and Palaeocene bird species, the researchers concluded that the specimen represents the earliest known relative of the “banana eaters”, the Turacos (Musophagidae family).

Turning to the Fossil Record

Turacos today are entirely restricted to sub-Saharan Africa. This enigmatic family of birds are renowned for their bright, gaudy plumage, elaborate head crests and some species have very loud alarm calls (hence their nick-name in parts of Africa, “go away birds”). The feathers of several species contain unique pigments that generate bright green and magenta tones.

If the American fossil bird F. panarium is indeed a basal member of the Musophagidae, then it suggests that these birds had a much wider, global distribution in the distant past. If this is the case, then why are extant Musophagidae members restricted to Africa?

Biogeographical and Bayesian Statistical Phylogenetic Analysis

Furthermore, an examination of the fossil record of Aves, suggests that Foro panarium is not the only example of a fossil bird being discovered outside the modern geographical distribution for that kind of bird. For example, the Trogoniformes (Trogons and Quetzal birds), which are restricted to the Southern Hemisphere today, have basal members preserved in fossils from the Messel Shales of Germany.

The Beautifully Preserved Remains of a Bird from the Messel Shales of Germany

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The scientists confirm the complex historical biogeography of crown birds across geological timescales. The geographical distribution of ancient species and their subsequent radiation and restriction is likely to be much more complicated than previously thought. The idea that the common ancestor of all living birds (Neornithes), arose in the Southern Hemisphere is not discounted, but this paper suggests that this assertion may not be as strongly supported by the evidence as previously thought.

Commenting on the significance of this study, Dr Field stated:

“Our picture of bird evolutionary history will continue to grow sharper as each new bird fossil gets unearthed.”

Shedding Light on the Turaco Lineage

It is likely that the birds went through a rapid phase of evolution after the End-Cretaceous extinction event that saw the demise of many ancient avian groups as well as the non-avian dinosaurs. A seed-eating diet, may have helped numerous lineages to persist as the world’s ecosystems recovered.

To read a recent article about this: Seed Eating May Have Helped Some Types of Bird to Survive the Cretaceous Extinction Event.

For the F. panarium fossil specimen itself, it may provide vital clues as to the age of the Musophagidae. Turacos must have diverged from their closest living relatives by at least 52 million years ago, (by the middle of the Ypresian faunal stage), thus supporting the idea of a rapid diversification of the Aves during the Palaeocene Epoch.

The fossil also provides some intriguing insights into the evolution of modern Turaco biology. Living Turacos have short hindlimbs and hind feet claw adaptations to help them to perch in trees. In contrast, the fossilised hindlimbs of Foro panarium are quite long, suggesting that this bird was more of a ground-dweller than its modern descendants.

The scientific paper: “A North American Stem Turaco, and the Complex Biogeographical History of Modern Birds” by Daniel J, Field and Allison Y. Hsiang published in the journal BMC Evolutionary Biology.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.