Early Bird Wings Preserved in Amber from Myanmar

A team of international scientists including researchers from Bristol University, have published research on two specimens of 99-million-year-old amber from Myanmar (called burmite), which have revealed the preserved remains of two tiny, baby birds. The scientists conclude that these birds were active shortly after hatching (precocial). Sadly they met their demise when they became trapped in sticky tree resin.

Fossilised Bird Wings

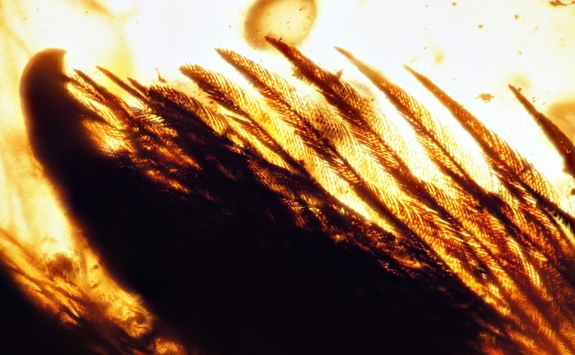

The Amber Has Preserved the Feathers in Exquisite Detail

Picture credit: Royal Saskatchewan Museum (R.C. McKellar)

The photograph above shows a close up of the feathers preserved in one of the burmite specimens. The researchers led by Dr Xing Lida (China University of Geosciences), along with colleagues from the USA, Canada and Professor Mike Benton from the School of Earth Sciences (Bristol University), have identified three long fingers, each tipped by a sharp and strongly curved claw, one of which can be seen in the top right of the picture above.

Amber Fossils from Myanmar

Amber fossils from Myanmar (formerly called Burma), have provided palaeontologists with a fascinating insight into life in the primordial forests of the Cretaceous. In the spring, Everything Dinosaur published two articles regarding remarkable fossil discoveries which had only been possible due to fossil finds within burmite. In one article, we reported on the potential origins of the malaria parasite, in the second we provided information regarding the discovery of the fossilised remains of tiny lizards.

To read about the evolutionary origins of the malaria: The Origins of Malaria Traced Back 100 Million Years.

To read more about the lizard fossil discovery: Lizards Preserved in Amber.

Although Burmese amber has produced fossils of isolated feathers, this is the first time in which portions of birds have been discovered.

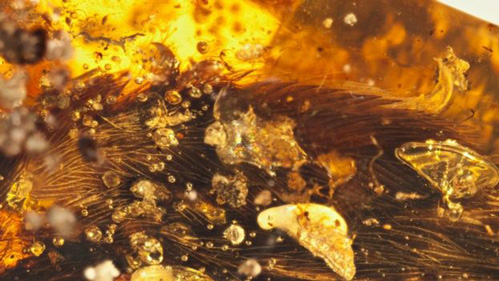

One of the Fossil Specimens Has Been Nicknamed “Rose”

Picture credit: Royal Saskatchewan Museum (R.C. McKellar)

Tiny Fossil Wings

The fossil wings are very small, between two and three centimetres long. the long, bony fingers can be made out along with the three digits on each wing. The anatomy of the hand has allowed the scientists to identify these as members of the Enantiornithines (Enantiornithes), group of birds, a diverse clade of toothed birds that possessed prominent wing claws. The Enantiornithines, thrived during the Cretaceous and some eighty species have been named, although a number are only known from single bones. These birds became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous and they are thought not to have been very closely related to modern Aves (Neornithes).

Under High Magnification the Fine Details of the Feathers Can Be Clearly Made Out

Tiny details on the feathers have been preserved. Ultraviolet light and X-rays were used to analyse the fossil material.

Evidence of Precocial Behaviour in Enantiornithes

Evidence of Precocial Behaviour in Enantiornithes

The two specimens have been nicknamed “Rose” and “Angel Wings”. After careful polishing, the fossils were analysed using white light, UV light and powerful X-rays.

Commenting on the research, one of the authors of the paper published in the academic journal “Nature Communications”, Professor Mike Benton stated:

“These fossil wings show amazing detail. The individual feathers show every filament and whisker, whether they are flight feathers or down feathers, and there are even traces of colour – spots and stripes.”

The scientists conclude that the birds, although babies were highly mobile. This indicates that these birds were very well developed when they hatched and capable of being independent from their parents. Sadly, their mobility seems to have been their downfall. As the clambered around the branches and trunks of trees they became trapped in sticky tree resin. Larger animals would have had the strength to pull free, but these youngsters were doomed. The amber even preserves claw marks and scratches as the birds tried to pull themselves free.

A Desperate but Ultimately Doomed Struggle

Picture credit: Chung-tat Cheung

Young Birds Trapped in Tree Resin

The beautiful illustration above shows an imagined scene in which one of these young birds find itself trapped and unable to break free of the glue-like tree resin.

Lead author of the study, Dr Xing Lida added:

“The fact that the tiny birds were clambering about in the trees suggests that they had advanced development, meaning they were ready for action as soon as they hatched [precocial]. These birds did not hang about in the nest waiting to be fed, but set off looking for food, and sadly died perhaps because of their small size and lack of experience. Isolated feathers in other amber samples show that adult birds might have avoided the sticky sap, or pulled themselves free.”

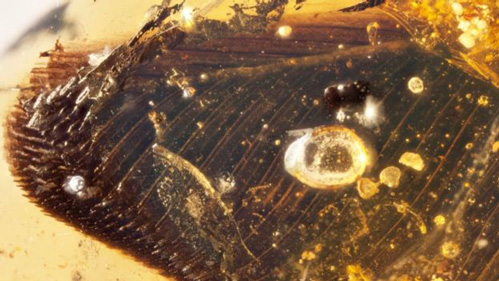

Scientists Can Identify Different Pigments in the Fossilised Remains of the Feathers

Different pigments in the feathers can be made out quite clearly in this feather preserved in Burmese amber.

Picture credit: Royal Saskatchewan Museum (R.C. McKellar)

For models and replicas of ancient prehistoric animals: PNSO Models and Figures.

Researchers Hope to Learn More About Aves/Dinosaur Evolution

Picture credit: Royal Saskatchewan Museum (R.C. McKellar)

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the help of Bristol University in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper from which this article is drawn: “Mummified precocial bird wings in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber” by Lida Xing, Ryan C. McKellar, Min Wang, Ming Bai, Jingmai K. O’Connor, Michael J. Benton, Jianping Zhang, Yan Wang, Kuowei Tseng, Martin G. Lockley, Gang Li, Weiwei Zhang and Xing Xu.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment