Cute Ancient Mammal Lived in Tough Cretaceous Times

A superbly preserved fossil of an early type of mammal found in sediments that date from 125 million years ago (Early Cretaceous), demonstrates that mammals had effectively evolved the same type of fur seen in extant mammals today. Many of these mammals may have been very small. Their fur provided them with a defence against attack from dinosaurs and other predators. However, not everything was rosy in the Cretaceous garden for this little furry critter, in between dodging hungry dinosaurs and crocodiles it seems that it suffered from a fungal disease that attacked the hairs that made up its coat.

Mesozoic Mammals

The fossil was excavated from the limestone lake bed sediments at Las Hoyas in the Iberian mountains of Cuenca Province (central Spain). It was discovered back in 2012, when a field team under the direction of Angela Buscalioni (a palaeontologist at the University of Madrid), was exploring the finely grained sediments in a bid to find more specimens of early birds, fossils of which, have made the Las Hoyas site one of the most important Lagerstätten sites in the world for vertebrate fossils dating from the Barremian faunal stage of the Cretaceous. The almost intact fossil was brought to the University of Bonn. A paper detailing the discovery has just been published in the journal “Nature”.

Fossils from Las Hoyas

The animal which was around 22 cm long, has been identified as a member of the Eutriconodonta, a diverse Order of primitive mammals which probably evolved in the Jurassic. The phylogenetic relationship between eutriconodonts and modern mammals remains unclear, but many academics argue that these animals are closely to today’s mammals (monotremes, placentals and marsupials) than the Multituberculata. Everything Dinosaur, earlier this month reported on the discovery of a multituberculate mammal from New Mexico, an animal that lived just a few hundred thousand years after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs.

To read about this Cenozoic multituberculate: Mammals Quick off the Mark after Dinosaur Extinction.

Spinolestes xenarthrosus

This new species has been named Spinolestes xenarthrosus. The name roughly translates as “spiny, strange jointed one”. It is derived from the spiny, defensive hairs found on the back, whilst the species name refers to the strengthened joints of the vertebrae. A similar anatomical feature is seen in extant members of the Xenarthra such as anteaters, armadillos and sloths. It is also observed in a small shrew from the Congo Basin.

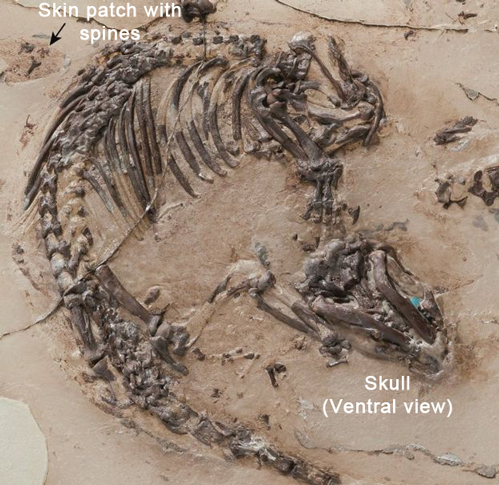

The Prepared Fossil Specimen (Spinolestes xenarthrosus)

Picture credit: Georg Oleschinski with additional annotation by Everything Dinosaur

The picture above shows the prepared holotype specimen that has been set in resin. The skull, seen towards the right of the photograph is viewed from below. An arrow (top right) points to a patch of preserved skin that shows dermal hairs which acted as defensive spines.

An Illustration of Spinolestes xenarthrosus

Picture credit: Oscar Sanisidro

Defensive Spines

As well as the defensive spines which probably broke off if a predator bit the back of this fast running mammal, letting Spinolestes escape but leaving the attacker with a mouthful of spines for their trouble, the rump of Spinolestes was partially covered in horny scutes. Commenting on these points, lead author Professor Thomas Martin (Steinmann Institute of Geology, Mineralogy and Palaeontology of the University of Bonn), stated:

“We are familiar with these characteristics in modern spiny mice from Africa and Asia Minor. If a predator grabs them by the back, the spines detach from the skin. The mouse can escape and the attacker is left with nothing more than a mouthful of spines. It is possible that these structures served a similar purpose in the case of Spinolestes.”

Best Preserved Mesozoic Mammal (Spinolestes xenarthrosus)

The fossil may well represent the best preserved mammal known from the Mesozoic and although described as mouse-like in some media reports, Spinolestes was only distantly related to modern mice (rodents).

Professor Martin explained:

“We are not able to classify the finding in any of the groups of mammals alive today. It displays characteristics which we also find in today’s mammals. However, these are not signs of relatedness but rather they developed independently – throughout the course of evolution, they have been ‘invented’ many times.”

This is an example of convergent evolution.

A Magnified Area of the Fossil Showing Guard Hairs (Proto Spines)

Picture credit: University of Bonn

It is likely that Spinolestes had a similar lifestyle to that of a mouse or a rat, scurrying through the undergrowth and using its keen senses to keep out of trouble. It may also have been nocturnal. The Las Hoyas deposits may lack dinosaurs (only a handful of different dinosaurs are known from the site), but there were plenty of other predators around capable of making a meal out of this particular eutriconodont.

A Strong Back

Convergent evolution also accounts for the anatomical features seen in the vertebrae. Individual bones in the back have supporting appendages that interlock the vertebrae together. The back is incredibly strong, much stronger than the backs of other similar sized animals. This feature is also found in the Hero Shrew (Scutisorex somereni) which comes from Central Africa. The Hero Shrew uses its strong back to help force itself under logs as it looks for insects to eat. It could be speculated that Spinolestes evolved a strong back for a similar purpose.

Signs of a Fungal Disease on the Fur

Such is the exquisite preservation of the fossil, that individual hairs of the fur can be studied. The state of some of the tiny fossilised hairs suggests that this animal was suffering from a fungal disease of the fur. This suggests that early mammals may have suffered from similar diseases as their modern counterparts. This fossil may help scientists to assess the taxonomic position of the Eutriconodonta in relation to extant mammals.

For models and replicas of prehistoric animals and other Mesozoic creatures: Mojo Fun Prehistoric and Extinct Models.

Summarising the team’s research, Professor Martin stated:

“One hundred twenty-five million years ago, Spinolestes was very well adapted to its ecological niche – through horny scutes and spines on its back as well as through its reinforced spine. We have to revise our thinking, mammals were indeed very small during the time of the dinosaurs. But they were certainly not primitive.”

To read an article on a carnivorous dinosaur, whose fossils have been found at Las Hoyas: One Lump or Two for a Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment