Let’s Hear it for the Neanderthals

A team of international scientists including palaeoanthropologists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, have been puzzling over the distinctive shape of the structures that make up part of the inner ear preserved in an ancient skull. The 100,000-year-old human skull has a similar inner ear structure to that thought to have only occurred in our near relatives the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis). CT scans have revealed to the researchers, something of a mystery, none of the other prehistoric human skulls dated to around 100,000 years ago and found in China show this inner ear formation. This discovery opens up the debate between H. sapiens and Neanderthal interaction and blurs the line between these two hominin species.

Neanderthal-like Inner Ear

The extremely detailed three-dimensional images revealed by the study, has raised important questions regarding the nature of late archaic human variation across Europe and Asia. It also suggests, that the inner ear shape once ascribed as being diagnostic of Neanderthal skull material may be present in other types of ancient human. This characteristic may not be a distinctive Neanderthal feature.

Researchers from the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology (IVPP – Chinese Academy of Sciences), in collaboration with Washington University (St Louis) and Bordeaux University (France), discovered the controversial evidence after a meticulous CT scan of a skull found in the Nihewan Basin of northern China.

The skull, found in the late 1970s along with other bone fragments and human teeth is known as Xujiayao 15, it was named after the archaeological dig site where it was discovered. The skull morphology indicates that it comes from an early non-Neanderthal form of late archaic human. It is probably the skull of a male.

Studying Human Evolution

Over the last two decades or so, the evolution of our own species and our relationship with other hominins has become somewhat blurred. For example, it was thought until very recently that Europe around 250,000 years ago was inhabited by just two species of humans, ourselves and the Neanderthals. New fossil discoveries and research on museum specimens has revealed that there may have been four different types of human in Eurasia at this time. As well as H. sapiens and H. neanderthalensis, evidence for the presence of Homo erectus and the enigmatic Denisovans has also been found.

To read an article that suggests the Denisovan hominins and the Neanderthals were closely related: Denisovan Cave Material Hints at Mystery Human Species.

Scanning the Inner Ear

The inner ear, also known as the labyrinth is located within the skull’s temporal bone. It contains the cochlea, which converts sound waves into electrical impulses that are transmitted by nerves to the brain. The inner ear also contains the semicircular canals, these chambers help us to balance and to co-ordinate our actions. These structures although small, have been found preserved in a number of mammal skulls including prehistoric human fossils. Research published almost two decades ago, which relied on less powerful CT scans and computer technology, established the presence of a particular pattern of the semicircular canals in the temporal labyrinth as being diagnostic of Neanderthal skull material.

The same pattern of the semicircular canals is found in all known Neanderthal labyrinths. As a result, the labyrinth has been used extensively as a marker to distinguish Neanderthal skull fossil from other hominins.

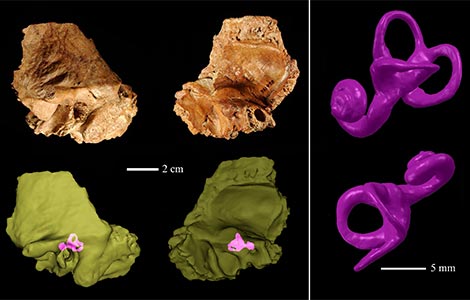

The Fossil Location with an Overlay of the Temporal Bone and CT Scan showing the Inner Ear Structure

Picture credit: Wu Xiujie (Chinese Academy of Sciences)

Academic Paper Published

The academic paper that details the international team’s research has just been published in the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences”. The shape of the skull and structures such as the arrangements seen in the semicircular canals could be used to help resolve the evolutionary relationships between a number of closely related human species.

Dr Erik Trinkaus (Washington University), one of the lead authors of the scientific paper, suggests that whilst it may be tempting to speculate on potential cross-breeding between the lineage that would lead to modern humans and Neanderthals, this may be over simplifying what is in effect a very complex relationship between different populations of prehistoric humans.

The finding of a Neanderthal-shaped labyrinth in an otherwise distinctly “non-Neanderthal” sample should not be regarded as evidence of population contact (gene flow) between central and western Eurasian Neanderthals and eastern archaic humans in China. Dr Trinkaus and his colleagues state that the broader implications of the Xujiayao skull CT research remain unclear.

Neanderthal-like Ear Structures Found in a Non Neanderthal Skull

Picture credit: Wu Xiujie (Chinese Academy of Sciences)

The picture above shows the temporal bone of the Xujiayao specimen (brown) and CT scans (green) with the shape and position of the temporal labyrinth outlined in purple.

Dr Trinkaus commented:

“The study of human evolution has always been messy, and these findings just make it all the messier. It shows that human populations in the real world don’t act in nice simple patterns. This study shows that you can’t rely on one anatomical feature or one piece of DNA as the basis for sweeping assumptions about the migrations of hominid species from one place to another.”

It looks like the human “family tree” has a more twisting branches than previously thought.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the help of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in the compilation of this article.

Leave A Comment