Biggest Flying Bird Ever Described by Scientists

A Seagull on Steroids – Pelagornis sandersi

A team of scientists from the Bruce Museum (Greenwich, Connecticut, USA), have published a paper on a new species of giant bird, believed to be the largest flying bird known to science, eclipsing the giant, prehistoric condor Argentavis magnificens. With a wingspan estimated to be between 6.1 and 7.4 metres, this is more than twice the size of the wingspan of the largest living flying bird today, the Royal Albatross (Diomedea epomophora) and places P. sandersi alongside the biggest members of the pterosaur family the Pteranodontia in terms of size. Its wingspan is only exceeded by a handful of flying reptiles, most of which belong to the Azhdarchidae pterosaur family.

Giant, Volant Bird

In simple terms, the wingspan of this newly described Oligocene bird was easily longer than the height of the tallest giraffes living today.

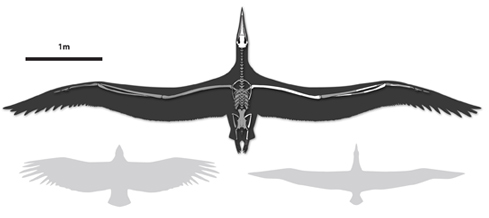

A Line Drawing Showing the Size and Scale of Pelagornis sandersi

Line drawing of World’s Largest-Ever Flying Bird, Pelagornis sandersi, showing comparative wingspan. Shown left, a California Condor, shown right, a Royal Albatross.

Image credit: Liz Bradford

The line drawing in the picture above also reveals how much of the fossil skeleton has been found (marked in white).

Pelagornis sandersi

The fossil material was discovered by James Malcolm, a volunteer from Charleston Museum (South Carolina), when a fossiliferous bone bed representing a marine environment was exposed during the building of a new terminal at Charleston International Airport in 1983. The strata forms a component of the Chandler Bridge Formation dated to the Late Oligocene epoch (Chattian faunal stage). A number of fossils of other marine birds were identified including fragmentary and badly distorted fossil elements from a smaller pelagornithid, but it is not clear whether these fossils represent a juvenile P. sandersi or a new species.

Studying Pelagornithids

The pelagornithids were a group of strange, “pseudo-toothed” birds, whose fossils have been found in a number of Cenozoic aged fossil sites which represent marine environments. It is likely that these creatures evolved in the Late Palaeogene and survived up until the end of the Pliocene epoch, going extinct around three million years ago. Although, a number of species had large wingspans, these birds were very lightly built with paper thin bones, as a result of which, their fossils are extremely rare. They were great aeronauts and were geographically very widespread with a number of specimens known from places as far apart as Chile and Australia.

To read an article about the discovery of a giant pelagornithid from South America: Giant Seabird from Chile.

Article about the discovery of fossils found in South Australia: Giant Toothed Birds once Soared over Australia.

The “teeth” of these birds have no enamel. They are in effect bony projections from the jawbones, they may not be true teeth but they were sharp and would have proved very effective in grabbing the prey of this large, ocean-going flyer. It is likely that Pelagornis sandersi caught fish and squid at the sea surface. Scientists remain uncertain as to whether this creature was capable of diving to catch prey.

Dr Daniel Ksepka Examines the Skull of P. sandersi

Picture credit: Bruce Museum

Flight Capabilities of Pelagornis sandersi

Dr Daniel Ksepka is the author of an academic paper which appears this week in the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences”. This paper explores the flight capabilities of Pelagornis sandersi. Although very large, the delicate bones suggest that this bird was very light. Body weight estimates vary between 21 and 40 kilogrammes and the weight plus wingspan parameters have influenced the calculations of this creature’s ability to glide. There is no doubt that this bird was an accomplished flyer, capable of travelling long distances, but the glide speed has been difficult to estimate because of the fragmentary fossil evidence.

A range of glide speeds have been stated, by Dr Ksepka (lead author), from an impressive 10.6 metres per second to more than 17 metres per second. To place this into context, Usain Bolt’s one hundred metres World Record of 9.58 seconds suggests an average speed over the race of around 10.4 metres per second, P. sandersi could effortlessly glide faster than Usain Bolt can sprint. When the upper estimates are considered, Pelagornis sandersi could travel at speeds in excess of 38 miles per hour.

An Artist’s Reconstruction of the Giant Seabird Pelagornis sandersi

Picture credit: Liz Bradford

Commenting on his study, Dr Ksepka stated:

“Pelagornithids were like creatures out of a fantasy novel, there is nothing like them living today.”

It is very likely that this family of birds adapted to a long-range, marine soaring strategy just like extant albatrosses, the bigger the pelagornithid the greater distances it was able to travel. The highly modified wing bones would have given this bird very long, slender wings, ideal for gliding.

Dr Ksepka added:

“Pelagornis sandersi could have travelled for extreme distances whilst crossing ocean waters in search of prey”.

Quite Clumsy on Land

As well as the exceptionally well-preserved skull, bones from the right hind limb have been found. These bones indicate that this bird would have been relatively clumsy on land. It probably could not take off simply by leaping into the air and flapping its great wings, it probably needed to run down hill or jump off a cliff edge in order to take to the air. Although it is difficult to ascertain the length of the primary feathers, it has been suggested that the primary feathers (the longest feathers found on the wing tips), would perhaps have measured more than a metre in length.

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur commented:

“This is a truly astonishing fossil. Such delicate and fragile bones are rarely preserved in the fossil record and thanks to the work of Dr Ksepka and his colleagues we are beginning to get a detailed insight into how these extraordinary birds lived. The flight capabilities of this marine bird are simply astonishing. For example, even at the lower end of the estimates for gliding speed, Pelagornis sandersi would have been capable of amazing feats of flight. It would have been able to cross the entire Gulf of Mexico in less than a day!”

The species name honours retired Charleston Museum Curator Albert Sanders, who originally collected the fossil material.