The United Kingdom’s Important Contribution to Palaeontology in the 19th and 20th Centuries

What Significant Contributions to Palaeontology has the United Kingdom Made Throughout the 19th and 20th Centuries?

This is not an easy question to answer. After all, to provide a comprehensive overview of the contribution made in the course of two hundred years by the scientists, academics and indeed laypeople of the British Isles is no easy task. In short, when the sciences of palaeontology and geology are considered, it could be argued that this little part of western Europe has punched well above its weight in the 19th and 20th centuries and it continues to do so.

Let’s focus our attention on just a few key, pivotal moments in a bid to shed more light on the prehistoric animals depicted in the recently released Royal Mail stamps that aimed to highlight the UK’s contribution to palaeontology. All the prehistoric animals featured are vertebrates and from the Mesozoic era, so we will restrict ourselves for the time being, to animals with backbones that lived during the “Age of Dinosaurs” as it is often referred to.

Palaeontology

This means that we have to disregard, on this occasion, the work of the likes of Sir Roderick Murchison (1792-1871), a remarkable Scotsman, one who fought in the Napoleonic Wars and later in life, working alongside the Yorkshire born Reverend Adam Sedgwick (1785-1873), helped map, classify and date geological strata in one of the first studies of its kind. Many of the geological periods before the “Age of Dinosaurs” were named and described by British scientists. Not surprising really, after all, the age of the rocks that make up the British Isles are extremely varied and we have had a long history of higher education and scientific study.

The Geological Society of London is the oldest geological society in the world, formed in 1807. In contrast, the Geological Society of America was not founded until 1888 and the Geological Society of China did not come about until 1922.

Confining ourselves to vertebrates of the Mesozoic also prevents us from detailing the contribution of Marie Stopes (1880-1958), perhaps better known as a campaigner for women’s rights and family planning, but also an expert in ancient flora who did much to unravel the mysteries of the evolution of flowering plants (angiosperms), or indeed the work of Professor Jenny Clack who in the last year’s of the 20th century helped to re-write the evolution of the first back-boned animals that evolved adaptations for living on land. Her analysis of the primitive tetrapod known as Acanthostega (Ah-can-tho-stay-ga) offered dramatic new insights into how fish made the transition to a life on Terra Firma.

Incidentally, Acanthostega lived during the Devonian, a period of geological time named after that county in south-west England, perhaps better known for its cream teas and sandy beaches.

British Women in the Earth Sciences

Let us continue to highlight the role of British women in the Earth sciences by focusing on the work of Mary Anning (1799-1847). Mary was a pioneering, fossil collector born just a few miles to the east of the county of Devon, in the small, seaside town of Lyme Regis (Dorset). Although lacking any formal scientific training and as a woman, sadly not given full credit for her work until long after her death, a consequence of, thankfully, now outdated Georgian and Victorian attitudes to the role of women in science. Mary explored the fossil rich, Jurassic aged strata of her Dorset home, she is accredited for finding the first plesiosaur fossils and the first ichthyosaur skeleton to be correctly identified as an ancient, marine reptile.

“Jurassic Coast”

An Ichthyosaurus and a Plesiosaurus both feature in the recent Royal Mail stamps issue, however, Mary Anning’s links with this stamp set is not restricted to the marine reptiles. It was Mary who discovered the first Dimorphodon specimens in the Lower Lias of southern England’s famous “Jurassic Coast”. This flying reptile also features in the Royal Mail series and the first fossils of Dimorphodon link to two other giants of nineteenth century British palaeontology, as Mary passed her pterosaur fossil to the Reverend William Buckland to study. It was Buckland, who wrote the first full, scientific description of a dinosaur (Megalosaurus – also featured in the stamp set) and Sir Richard Owen, a Lancastrian, who first coined the term Dinosauria, was responsible for erecting the Dimorphodon genus in 1870.

The Gravestone of Mary Anning and Joseph Anning (brother)

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Dinosaurs from Britain

The pair of Iguanodons, beautifully illustrated by John Sibbick on one of the stamps is a reminder of the role played by this country in fundamentally changing scientific thinking about prehistoric life and the history of our planet. Gideon Mantell, a medical man by training but with a passion for geology and palaeontology, did much to broaden our understanding regarding the prehistoric animals of the Cretaceous. It was Mantell who first scientifically described Iguanodon and this dinosaur was one of the first to be reconstructed both as a mounted skeleton and as a representation of a living animal.

The United Kingdom has made a significant contribution to the popularising of science, especially the study of prehistoric animals. Scotsman Bill Swinton (1900-1994) is credited with writing one of the first ever textbooks on dinosaurs. The book, first published in 1934 with the catchy title “The Dinosaurs: A Short History of the Great Group of Extinct Reptiles”, became a standard text for students of palaeontology all over the world for the next forty years or so.

The Iguanodons that Feature on the Royal Mail Stamps

Life-size replicas of prehistoric animals built by London born Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and first put on display in 1854 can still be seen today in south London’s Crystal Palace Park. These concrete replicas, the first of their kind to be exhibited anywhere in the world now have Grade 1 listed status (the same status as Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace). The general public’s fascination for everything dinosaur seems to have continued non-stop and many British academics have been in the vanguard of popularising the study of ancient life and prehistoric ecosystems.

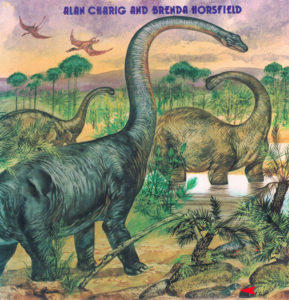

To end our very brief foray into the contribution made to palaeontology and geology in the 19th and 20th centuries by the United Kingdom, it seems fitting to end our short discourse by paying tribute to Alan Charig (1927-1997), a research scientist who rose to become Curator of Fossil Amphibians, Reptiles and Birds at the Natural History Museum. Dr Charig did much to popularise the subject of palaeontology in the 1970’s, with the BBC television series “Before the Ark”, the success of which, according to many commentators, paved the way for Sir David Attenborough to make the first of his ground-breaking natural history programmes (Life on Earth).

The Front Cover of “Before the Ark”

The 1975 BBC book “Before the Ark” depicts a small mammal (arrowed) in a world dominated by dinosaurs and other reptiles.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Alan Charig in conjunction with Angela Milner was given the responsibility of studying and scientifically describing a new type of predatory dinosaur unearthed by an amateur fossil hunter whilst exploring a Surrey clay pit in 1983. Almost seventy percent of the fossilised skeleton was excavated. This ten-metre-long leviathan was named Baryonyx (Bar-ree-on-niks) and the head and neck of this theropod dinosaur are depicted on one of the stamps in the Royal Mail set, a fitting tribute to the immense contribution made by the people of this country to the study of ancient life and in particular to the Dinosauria.

A Model of Baryonyx (B. walkeri)

Picture Credit: Everything Dinosaur

It is also worth noting the immense contribution paid to the prehistoric animal model industry by British designers and artists. For example, Anthony Beeson the creative force behind the much admired CollectA prehistoric animal model range.

To view the CollectA model range: CollectA Prehistoric World and Prehistoric Life Models.